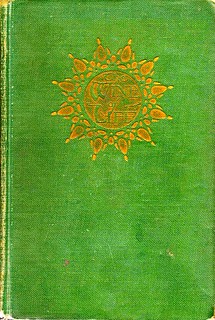

Arthur Stringer

New York: Knopf, 1921

389 pages

She was the original Gibson Girl, an Amazonian actress whose career was hindered by her height. He was a tall Adonis from Ontario, just beginning to make a name for himself in the world of letters. Together they were “the handsomest couple in New York.”

The romance between Jobyna Howland and Arthur Stringer began in 1900 with a chance encounter at a party on Washington Square. They married seven weeks later at the Little Church Around the Corner on East 29th Street.

Theirs was a shaky relationship, cushioned somewhat by the ever-increasing flow of money brought by Stringer’s writing. When it finally ended, in the spring of 1913, beautiful Jobyna returned to the stage and sought publicity by telling all in a series of syndicated newspaper features. “Peculiar Romance-Tragedy of an Actress and a Poet” ran one headline. The titillation promised by another – “How He Gave Himself Away!” – was tempered somewhat by the subheading:

What was Poor, Beautiful Jobyna Howland to Think When Husband Arthur Stringer Told Her That He Adored Her, and Then Wrote That Women Weren’t Necessary to Poets – COULD Any Wife Stand It?

I’d have thought most could.

There was no real scandal in the collapse of the Stringer marriage; the husband was never accused of infidelity, or even flirtatiousness. “It was just that he kept continually saying one thing and writing another,” reported one desperate wag.

Here are two examples:

The poet or artist seldom marries a beautiful woman. He marries a woman he imagines to be beautiful.

Woman is mysterious to man because no man can understand her until he abhors her. For the eye, both artists and scientists will tell you, sees more when looking down than when looking up.

Stringer’s “The Advantages of Being Ugly” may have been the final straw. The Toronto World ran this Swiftian essay a few days before Valentine’s Day, 1913, along with a photograph of Jobyna captioned: “Mrs. Arthur Stringer (Jobyna Howland), Who Was Gibson’s Original Model, but Who, According to Mr. Stringer’s Theory, Would Be Still More Successful If Ugly.”

Mrs. Stringer filed for separation shortly thereafter.

Unlike his wife, Mr. Stringer avoided the press during the break-up, expressing himself in verse:

ULTIMATA

I am desolate,

Desolate because of a woman.

When at midnight waking alone

I look up at the slow-wheeling stars,

I see only the eyes of this woman.…

I am processed of a great sickness

And likewise possessed of a great strength,

And the ultimate hour has come.

I will arise and go to this woman,

And with bent head and my arms about her knees

I shall say unto her: “Beloved beyond all words,

Others have sought your side,

And many others have craved your kiss,

But none, O body of flesh and bone,

Has known a hunger like mine!

And though evil befall, or good,

This hunger is given to me,

And is now made known to you,-

For I must die,

Or you must die,

Or Desire must die

This night!”

Arthur Stringer fancied himself a poet. Anyone questioning the man’s talent should consider Jobyna’s declaration that her heart had been won by “The Passing of Aphrodite”, verse composed seven years into their marriage.

“Ultimata” wasn’t nearly so effective. In the dying days of 1914, they divorced.

Stringer was a remarkably energetic writer. The years immediately following the dissolution of his marriage to Jobyna saw The Door of Dread (1915), The House of Intrigue (1916), The Hand of Peril (1918) and The Man Who Couldn’t Sleep (1919). It was also during this period that Stringer wrote The Prairie Wife (1915), a novel academics cite as influential.

The Prairie Wife has been out of print for over ninety years.

The vast majority of his novels were published by Bobbs-Merrill, a hugely successful publisher located, improbably, in Jobyna’s hometown of Indianapolis.

Then came The Wine of Life, a novel Bobbs-Merrill wouldn’t touch.

Published by Alfred A. Knopf, The Wine of Life is a an atypical work. It tells the story of Owen Storrow – rhymes with sorrow – a young sculptor who arrives in New York after having achieved certain success in his native Canada. That our hero is not a writer should not distract; The Wine of Life is a roman à clef born of the author’s relationship with Jobyna Howland.

Storrow has been in Manhattan but a short time before he encounters Torrie Thorssel (née Millie Roder), an actress with milk-white skin that reminds him of marble. They share drinks and a bed, after which the sculptor makes himself scarce.

Weeks go by.

Quite by chance, Storrow rents a studio adjacent to the one in which Torrie is staying. Their physical relationship resumes, leading Storrow, good Canadian boy that he is, to propose marriage.

The pair wed, though they keep the union secret from all but a couple of friends. “There’s my work to think of,” says the actress. “People aren’t interested in a married stage star.”

As it turns out, they’re not much interested in Torrie as an unmarried stage star either, though “Hebrew” Broadway producer Herman Krassler hovers around, determined to put her maiden name in lights.

The bride starts going through Storrow’s money – “You’ll find me a very expensive luxury,” she’d warned – as the Canadian sets aside sculpting to work on a novel that is best described as Stringer’s Empty Hands (1924):

“I always wanted to write the story of a man and a woman thrown empty-handed into the wilderness, tossed through some trick of fate into our northern Barren Grounds, for instance, as naked as Adam and Eve turned out of the Garden!”

He’s guided in the endeavor by friend Chester Hardy, a practical, workhorse of a writer who works to a schedule and eschews the Bohemian crowd in which Torrie circulates. When Storrow follows his example, it causes strain on the marriage.

Stringer himself was a workhorse. One of the wealthiest Canadian authors of his day, he treated writing as a business, his office as an office, Hollywood as a cash cow and pulp magazines as a herd. He recognized opportunity and proved adept at investing the riches earned through his writing

The Wine of Life is not nearly so commercial. Here the prose is elevated; greater care is in evidence, yet somehow the plot rambles. This reader wondered about the scattered, seemingly meaningless appearances by Storrow’s cousin Catherine. And what was the point of all that stuff about “Pine-Brae”, his fruit farm in Southern Ontario?

Again, The Wine of Life is not a commercial novel; no happiness is found in the ending:

Cousin Catherine is stuck in a passionless marriage, having married after the man she truly loves, Storrow, had chosen another.

Torrie marries Krassler, but this is only to further her career.

Storrow marries his perfectly nice housekeeper for the very same reason he wed Torrie: he’s sleeping with her and feels it is the right thing to do.

In our world, Arthur Stringer married his cousin – Margaret, not Catherine – shortly after the divorce from Jobyna. The couple spent much of their early years at “Shadow-Lawn” – not “Pine-Brae” – just south of Chatham.

Jobyna became engaged – fleetingly – to Andrew Freedman (né Friedman), a Broadway impresario who is better remembered today for having owned the New York Giants. He died in 1915, leaving her $150,000, which she promptly lost in the stock market.

As with all romans à clef, The Wine of Life is made more interesting through knowledge of the source material. It’s for this reason that I chased Jobyna Howland, a pursuit that led, surprisingly, to her friendship with H.L.Mencken. In My Life as Editor and Author, the curmudgeon’s posthumously published autobiography, Mencken places Jobyna with Ethel Barrymore as “the champion lady boozers of Broadway.” His accounts of the actress nearly always mention her height and her drinking. Mencken relates one particularly wet evening in which Jobyna broke down in tears:

It was simply impossible, she sobbed, for her to forget Stringer. She loved him as she had always loved him, and she would never love another. The quarrel that caused their divorce was a trivial one, and should have been patched up. Unhappily, Stringer married another woman immediately after the decree was issued, leaving poor Jobyna in desolation.

Adds Mencken: “The love agonies of a woman six feet in height are always extra poignant.”

The hurt behind the fiction.

As if this novel wasn’t already depressing enough.

From CNQ 93, The Rereading Issue (Summer 2015)