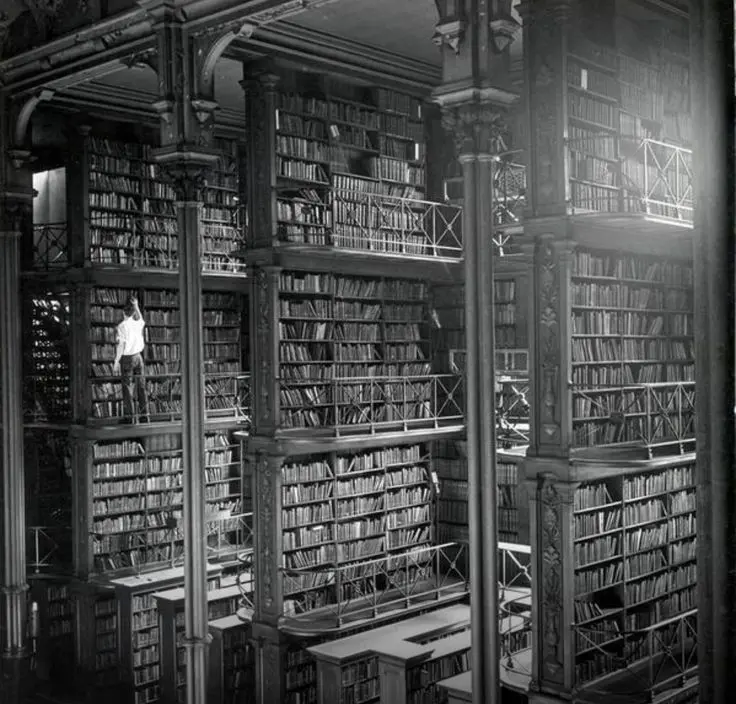

Spend half an hour wandering through the stacks of a decent sized library and you’ll quickly be overwhelmed by the crushing weight of the literary past. More books exist than even the hardiest reader could digest in a hundred lifetimes. Some are slim pamphlets, others hefty tomes, but when crammed together on the shelves they present a daunting challenge. “Of the making of books there is no end,” a Biblical proverb assures us. And if that was true in ancient times, how much heavier is the burden of textual matter in the age of print-on-demand?

Yet even as books proliferate with unabated abandon, there is a persistent tendency to want more, to be unsatisfied with what we already have and to want to recover what is irrevocably lost or fantasize about what could be. The impulse to dream up imaginary libraries is a strong one, recurringly shared by many writers in the overlapping traditions of satire and fantasy.

Towards the end of the Middle Ages, anonymously authored parodic liturgies and mock-Gospels started to pop up, filled with pointed jests aimed at clerical folly. These were the precursors to an episode in Rabelais’ sixteenth century masterpiece Gargantua and Pantagruel, where a giant wastes his time reading such nonce-books as On the Art of Discreetly Farting in Company by Magister Noster Ortuinus and Tartaretus: On how to Defecate.

In his 2006 study, The Library at Night, Alberto Manguel argues that Rabelais’ lengthy catalogue of make-believe tomes constitutes “perhaps the first ‘imaginary library’ in literature.” It shouldn’t surprise us that Rabelais’ bookish satire on scholastic nonsense appeared in the dewy dawn of the early modern period, when ancient masterpieces were being rediscovered and fresh volumes mushroomed as never before in order to keep newly built printing presses busy. The Gutenberg era was in full swing and Rabelais was registering the appalling fallout.

Post-Rabelais, countless other satirists – Dryden, Swift, and Pope spring to mind – took up the job of writing fiction-within-fiction, filling their books with fabricated poets and battling books, complete with pseudo-scholarly footnotes. Perhaps the culmination of this tradition is Borges’ “The Library of Babel,” which can be read as the lucid nightmare where the world becomes a vast and stifling storehouse for books maintained by a decadent culture that has forgotten how to really read.

As against the sly jocularity of Rabelaisian satire, imaginary books fulfill a more wistful and fanciful role in fantastic literature. In trying to make the flesh of his readers itch and twitch, H.P. Lovecraft occasionally refrained from describing his tentacled monsters and simply gave the title of the ghastly grimoires used to summon the Old Ones, most famously the Necronomicon. Lovecraft endowed his fictional Miskatonic University with a rich library of lurid volumes, possibly the inspiration for the library at Hogwarts in the Harry Potter series and many other concocted book collections.

The books and stories that only have a wraithlike half-life within another work of fiction can leave a surprisingly permanent stain on the memory. In another otherwise mediocre Sherlock Holmes story, the great detective makes an aside about “the giant rat of Sumatra, a story for which the world is not yet prepared.” This tossed-off remark is my favourite passage in the Holmesian canon. What on earth is the giant rat of Sumatra? Why is the world not ready to hear about it yet? When will we be prepared to hear about it? Arthur Conan Doyle was wise enough to refrain from answering these queries since the suggestive power of his few words are much more electrifying than any fully drawn out story could be. Alas, several pastiche-ists have lacked Conan Doyle wisdom and have tried, with a predicable lack of success, to delineate the rat’s tale.

Hints and fragments, the great modernists have taught us, can leave a much stronger impression than a story where both detail and themes are explicitly laid out. Lord knows Conan Doyle was no modernist, but with the happy accident of “the giant rat of Sumatra” he hit upon the aesthetics of fragmentation and the partial glimpse, the scattered fossils that we can use to reconstruct the dinosaur, the shards of pottery that evoke an ancient civilization. Derek Walcott keenly described the aesthetics of fragmentation in these words: “Break a vase, and the love that reassembles the fragments is stronger than that love which took its symmetry for granted when it was whole.” Much of modern art takes its passion from the idea that the world is a shattered vase which is impossible to repair except through an act of the imagination.

Making up non-existent books is a metaphor for creativity itself. Every earnest writer starts with the assumption that the world’s libraries, no matter how overstuffed, are still insufficient, that there is a lacuna that needs to be filled by more books. What other honest motive is there for writing?

Imaginary comic books and libraries are a recurring feature of the recent stories of the cartoonist Seth, who turns out be heir to the dual traditions of satire and fantasy that have made fictional books a central motif. Readers of Canadian Notes and Queries will of course remember that Seth gave us a tour of “the crumbling, but once grand headquarters” of this magazine which supposedly exist “in the trackless wastes beyond Emeryville” (CNQ 79). In the North Wing of the CNQ building smoulders the burnt-out husk of the once grand archive. All that survives are a few scattered pages from “the remains of section 741.5 – cartoons, comics and graphic novels. Scores of graphic novels, each an original CanLit adaptation. Each, the only copy in existence.” From this invaluable collection, all that could be rescued are “some short passages… a few scenes” (CNQ 80). The North Wing is thus a library of scraps and fragments.

The tragic tale of the North Wing serves as the pretext for the two-page comics adaptation of CanLit classics that run in every issue of CNQ. But the story also illustrates Seth’s grounding in the aesthetics of fragmentation. A full-length graphic novel adaptation of Marian Engel’s Bear could easily be plodding and wearisome. But if you have cartoonist Joe Ollmann illustrate a two-page snippet from Engel’s novel that purports to be the sole surviving scrap of a larger work, then the reader is given a seedling that can germinate in the mind.

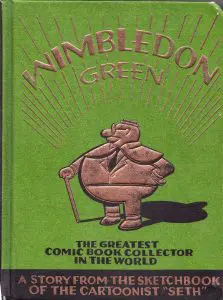

Seth’s 2005 graphic novella Wimbledon Green started off as a series of sketchbook spoofs on the often nutty world of comic book collecting but acquired an extra layer of parodic energy and historical resonance by the many made up comic books that litter the story. Many of these comics seem simply absurd, for example Fatsy #7 (the “infamous flatulence issue – most copies destroyed” and valued at $3,000 mint). Yet as these fancied comic-books accumulate, Seth is able to evoke the misty-eyed passion that collectors have for their oddball objects of desire. One of the highlights of the book is an extended reverie on “Fine & Dandy” – an imaginary comic book series devoted to the hijinks of a pair of Laurel and Hardy-style hoboes. Wimbledon Green’s fervent advocacy of “Fine and Dandy” makes you want to read their adventures, transforming you into a participant in his collecting mania.

Seth’s latest graphic novella The Great Northern Brotherhood of Canadian Cartoonists (or The G.N.B. Double C, GNBCC) is in many ways a companion volume to Wimbledon Green and, like the earlier book, can be read as pseudo-bibliographical enterprise, a catalogue of largely non-existent creations. The book’s confessedly unreliable narrator offers a guided tour of the history of Canada’s cartooning past, a survey of history that cunningly mixes fact and free-floating fancy. In Seth’s crazy-quilt mixture of actuality and fantasy, actual cartoonists like Doug Wright and Chester Brown jostle against Yvette Mailloux (creator of an long-running anticlerical comic strip allegedly popular in Quebec) and Sam Middlesex (whose multi-volume, multi-generational graphic-novel roman fleuve seems like an alternative universe version of Hugh Hood’s The New Age/Le nouveau siècle).

Perhaps the highlight of The GNBCC is the account of The Great Northern Archive, where the treasures of our national cartooning heritage are kept. Shaped like a cluster of igloos and built in the wake of the centennial patriotism of 1967, the Great Northern Archive is in an impossibly remote location. To get to it you have to take a train far north “past towns with names nobody’s heard of.” Then you go on a steamship, which takes you to the misnamed village of Green Valley, where a rickety school bus carries you to the archive during the summer. In the winter you have to rely on a dog sled. “Needless to say, on one visits in wintertime,” we’re told. “During those months the librarian and her assistants are virtually prisoners of the north.”

The remoteness of this imaginary archive is a neat metaphor for the difficulty of acquiring historical knowledge, for the hard-won journey that is necessary if you want to gather up the fragmentary leavings of an earlier time. In the age of eBay, Abebooks, and YouTube, we may think that the whole historical past is only a few clicks away. But in point of fact, actually possessing information about the past will always take time and effort. If the past is a foreign country, it’s one that requires an arduous journey to visit.

In real life, Seth is a collector, archivist, and historian. The history of cartooning is largely uncultivated soil and to learn the lore of his craft Seth had to spend countless hours scouring through used bookstores and other dingy havens of antiquarian artefacts. The fruits of his excursions into the pop culture past are evident in the archival reprint projects he’s worked on (The Complete Peanuts, Doug Wright’s Family, and the volumes of the John Stanley Library) as well as his essays championing various half-forgotten cartoonists. The creation of the Doug Wright Award is another prong in Seth’s engagement with comics history. Taken together, these activities have had a profound impact on how those of us who care about comics understand the evolution of the form.

But if the genuine flesh-and-blood Seth is constantly researching the history of comics, he has an imaginative alter-ego who flares up in the pages of Wimbledon Green and The GNBCC (which is quite literally so: both books have characters who are carbon copies of the cartoonist). This Seth-doppelganger is less interested what happened in the past than what could have happened. The alternative-Seth is all about the pleasures of supposition, the joy of conjecture, and giddy delights of hypothesis. Just as the real Seth fills his library with actual books and comics, the shadow-Seth dreams of all the books and comics that never were but should have been.

Taken together, the real Seth and his shadow self have given us a rich addition to the literature of imaginary libraries, works that offer a distinctive combination of the snark of satire with the pensiveness of fantasy.

From CNQ 86, The Library Issue (Winter 2012)