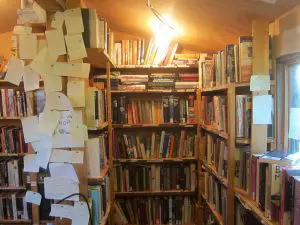

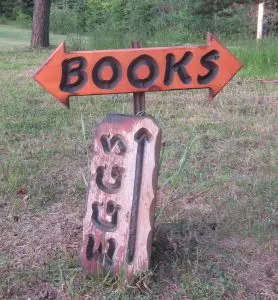

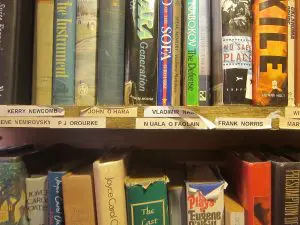

The name of the World’s Smallest Bookstore is only a slight exaggeration. The original store, the one you first notice when you drive down Highway 503, just north of Kinmount, Ontario, is a tiny, five-foot-by-eight-foot converted chicken coop with a neatly shingled roof crammed floor-to-ceiling with bookshelves overflowing with literature A through Z. Literature, A–Z. It’s not unusual to find a few shelves in the junk shops you encounter up north devoted to the novels of Stephen King and Nora Roberts, weight loss and home renovation how-to volumes, mouldy textbooks and cheap Bibles, but literature is harder to locate. You might come across the must-read novel of publishing seasons past, its jacket covered with all of the impressive-sounding awards it won and several years of dust and indifference, but even that’s a rarity. The World’s Smallest Bookstore makes its tastes immediately known as you approach the front door (the only door it has), several wood-burnt signs proudly proclaiming Jane Austin and Robertson Davies and Charles Dickens and Alice Munro and Walt Whitman and some illustrious others. It’s Western literature’s very own Northern Ontario fan club and clubhouse.

I first came across the World’s Smallest Bookstore in 2009, shortly after my wife, Mara, and I bought a half-acre rural getaway nearby. I was living in Toronto at the time, had just turned forty, and suddenly found myself craving closer contact with trees and earth and open sky. (Mara is from northern Ontario and was way ahead of me in desiring less concrete and fewer sirens and car alarms in our lives.) I soon learned that red wine and MLS.com are a dangerous combination. After enough of the former, it seems entirely rational to conclude that, on the one hand, the property you discovered online is in Nova Scotia, but, on the other, that it’s only $65,000, is a hundred years old, and has a wraparound porch that overlooks the bay. Another glass of merlot and you’ve convinced yourself that commuting to a summerhouse on the other side of the country would have its undeniable challenges but is definitely doable. Definitely. Then, in the morning, you wash up the dirty wine glasses and regret the late-night emails sent to friends and family about this week’s must-have dream property and pledge, once again, not to pilot the information superhighway pie-eyed.

And so on until we finally found a place that met all our buying criteria (cheap enough; within a three-hour commute to Toronto; on a lake or a river), though it wasn’t until we moved in that we realized it had a feature we could never have even hoped for: a 24-hour bookstore a short walk away, where every volume was three dollars, just like the fresh eggs for sale in the fridge near the political biographies section.

*

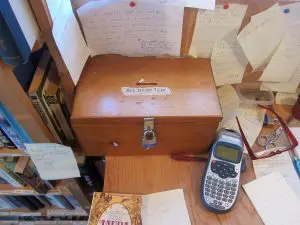

Other than the books themselves, the only other thing you’ll find inside the World’s Smallest Bookstore is a grey metal cashbox where you insert three dollars for every book you’ve bought (it’s operated entirely on  the honour system) and a clipboard and pen to write down the name of the author and the title purchased, and – if you’re so inclined – any comments you’d care to leave. And people quite often are inclined, saying things like “Thank you for your wonderful bookstore,” “What an oasis of literature,” and “Please keep doing what you’re doing, it’s important.” You’re asked to use the clipboard in the same way when purchasing anything from the cinderblock annex (about the size of two large car garages) at the rear of the property. You can’t miss it – it’s right next to the chicken coop and the pen where the goat lives.

the honour system) and a clipboard and pen to write down the name of the author and the title purchased, and – if you’re so inclined – any comments you’d care to leave. And people quite often are inclined, saying things like “Thank you for your wonderful bookstore,” “What an oasis of literature,” and “Please keep doing what you’re doing, it’s important.” You’re asked to use the clipboard in the same way when purchasing anything from the cinderblock annex (about the size of two large car garages) at the rear of the property. You can’t miss it – it’s right next to the chicken coop and the pen where the goat lives.

Here it’s not just fiction, but poetry, essays, politics, religion, sports, philosophy, biography, music, and more. (Including mosquitoes, in the spring and early summer, because the door is usually left open and the lights are always on.) Some of my greatest World’s Smallest Bookstore discoveries have come from this room: a hardback, Faber and Faber edition of Philip Larkin’s delightfully acerbic collection of music criticism, All What Jazz; the poet Karl Shapiro’s lone novel, Edisto; a first edition of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s Collected Poems. More often, though, it’s just an old paperback that catches the eye or rings a bell or some other book-collecting cliché, the wonderful, inexplicable serendipity that brings the right book into your life at exactly the right time.

Either way, if you do happen to strike out in the bibliophilic department (unlikely as that is – there are  approximately 15,000 volumes distributed between the two buildings), there are fresh eggs (from the coop next door, they don’t come any fresher) for three dollars a dozen and for which you pay for in a separate grey metal cashbox. Good poetry and farm-fresh poultry; and just a twenty-minute walk from our place on Mark Twain Road. Could a writer even conceive of a better rural hideaway? (Admittedly, as with most things, luck had a lot to do with it. The two roads that intersect with ours, Hobbit Lane and John Wayne Road, aren’t quite as storybook.) Someone once asked me the difference between “fiction” and “literature.” I said that in literature the dog dies at the end of the story; in fiction, the dog lives. Life is like literature. The World’s Smallest Bookstore is closing this summer. Permanently.

approximately 15,000 volumes distributed between the two buildings), there are fresh eggs (from the coop next door, they don’t come any fresher) for three dollars a dozen and for which you pay for in a separate grey metal cashbox. Good poetry and farm-fresh poultry; and just a twenty-minute walk from our place on Mark Twain Road. Could a writer even conceive of a better rural hideaway? (Admittedly, as with most things, luck had a lot to do with it. The two roads that intersect with ours, Hobbit Lane and John Wayne Road, aren’t quite as storybook.) Someone once asked me the difference between “fiction” and “literature.” I said that in literature the dog dies at the end of the story; in fiction, the dog lives. Life is like literature. The World’s Smallest Bookstore is closing this summer. Permanently.

*

The store’s creator and sole curator, Gord Daniels, moved to the Kinmount area in 1978 to work in the wood sign and plaque business. He always, he says, “loved books,” and for nearly twenty years assiduously collected them at every yard sale, church sale, and library discard sale he came across, eventually filling his entire house, including a spare bedroom that no one could enter anymore because it was so full. Sitting with him at the kitchen table in the house only a couple of hundred metres from the bookstore was his dog, Dash, who only a few minutes before had loudly announced my arrival but was now asleep with his chin on Gord’s slippered foot while the cane he uses to get around these days leaned against an empty chair. I asked him where the idea for the store came from. In a voice hushed but hoarse, and occasionally having to take a deep breath to help get the words out, “Because I always wanted to have my own bookstore,” he says. “I always liked being around books.” When I wonder aloud whether he ever worried about running the store strictly on the honour system, he says “I didn’t worry too much, because there wasn’t too much I could do about it.” (He continued working at the sign and plaque business until 2015.) As for why he decided to make it a 24-hour, 365-day-a-year enterprise, he pauses, clears his throat, and answers, “I thought it was best to go whole hog.”

*

Gord sold his first book in 2007, and for nearly ten years searched out those same yard sales, church sales, and library discard sales to constantly replenish the store’s stock. One of the pleasures of opening up our place every spring was seeing what fresh treasures Gord had managed to come up with over the winter. One summer evening, while working late on one of the essays in my book Why Not? Fifteen Reasons to Live, I found I needed a quotation from Heart of Darkness. Immediately. Tonight. We got in the car just before midnight and drove five minutes to the World’s Smallest Bookstore where we found a copy in the newly buttressed Joseph Conrad section and I got my quote. The book now sits on one of the shelves in my writing studio overlooking the Irondale River, where it will likely remain until age and/or illness compels us to sell what we’ve come to call “The Twain.”

Gord says age (he’s 78) and illness (“I’m just tired,” is all he’ll say; “He’s fine,” his wife, June, the person responsible for the chicken coop and the three-dollar eggs, adds, “it’s just that we’re all getting a little bit slower and slower”) are the reasons he’s put the World’s Smallest Bookstore, as well as the house and the several acres they sit on, up for sale. The couple is moving to nearby Bancroft, where June lived for twenty years, and where the winters won’t seem quite so long, and where Gord won’t have to worry about keeping his bookstore stocked, tidy, and operational. There was some hope initially that a buyer could be found who would keep the store open, but in the end the best offer came from a group who are going to turn the property into a marina. (Wood sign and plaque makers, like bookstore owners, generally don’t have pensions.) What will happen to the books that aren’t sold by the time the new owners take possession, I ask. “They’ll probably just throw them way,” Gord says quietly, running his hand over the smooth end of his walking stick.

Because the house they’ll be living in will be much smaller and lacking the accompanying acreage they’ve grown accustomed to, Dash is staying behind to live with the next-door neighbour where he’ll continue to be able to roam wherever and whenever he wants. “He’ll probably come looking for us in the beginning,” June says, “but he’ll get used to it. And the neighbours love him. We just couldn’t stand the idea of him being on a leash all day. He’ll be fine.” Standing in the kitchen doorway, she looks at her husband. “It’s going to be tough for Gord, though,” she says. “Losing the bookstore and his dog. But it’s for the best. For all of us.”

It probably is – for them – but not for me or my wife or the thousands of others whose lives have been enriched by the presence of a wonderful, improbable bookstore in the midst of the Haliburton Highlands. Before I leave, I try to impart some of this to Gord. “It was the most rewarding thing I’ve ever done in my life,” he says. There’s nothing else for either of us to say.

—A CNQ Web Exclusive, June, 2016