One explanation for feminism’s dissipation in our social discourse and particularly our fiction can be found in the third-wave movement’s varied inclusivity and refusal to set a definition, which is precisely the point of third-wave feminism. Second-wave feminism, the wave of the Pill and women’s lib., was eventually considered too militant and exclusionary: too white, too sex-negative, too academic, too female. Third-wave developed as an all-inclusive feminism, which, according to Jennifer Baumgardner, co-author of Manifesta: Young Women, Feminism, and the Future, “is something individual to each feminist.” However, the problem with keeping feminism undefined and mutable is that the stereotypes the second-wavers fought against creep back into public thinking and published fiction, brought back and advanced by women as well as men. When body shots and Girls Gone Wild can be considered not just feminist, but as feminist as Planned Parenthood, sooner or later nothing is feminist, and the same rights women fought for are replaced by the sexism we fought against. In such a climate, few dare to accuse a number of the novels written by Canadian women (February, Lullabies for Little Criminals, The Birth House) of being sexist and promoting negative roles for fear of being called anti-feminist as well.

In CanLit novels, two prominent types of female characters emerged from the pick-and-choose chaos of third-wave feminism: passive girls or girl-like women and past-obsessed (grand)mothers. Almost twenty years ago, while in the midst of earning my Bachelor of Arts at York University in Toronto, I was immersed in the peak of the third-wave, the shaven-headed riot grrrl, hyper-politically-correct feminism that smashed at glass ceilings and held hands during Lilith Fair sing-alongs. Female enrollment at post-secondary schools increased as the birth rate decreased. Then the riot grrrls grew out their hair and reclaimed femininity just as their daughters started wearing thongs to elementary school. My current university campus (Dalhousie) bears little resemblance to the York of yore: sockless ballet flats have replaced army boots and no Chelseas emerge from the sea of iron-haired blondes and hijabs. Today, Canada’s birth rate is higher than it was in 1995 as professional women return home from the jobs their mothers fought for to live the housewife lives their mothers fought against. With fewer women on the frontlines of feminism, with fewer examples of feminist characters in our literature, it’s easier to default back to stereotypical gender roles. The predominance of such characters in our novels is extremely problematic. As Adrienne Rich writes, “If the imagination is to transcend and transform experience it has to question, to challenge, to conceive of alternatives, perhaps to the very life you are living at that moment. You have to be free to play around with the notion that day might be night, love might be hate; nothing can be too sacred for the imagination to turn into its opposite or to call experimentally by another name. For writing is renaming.” Our women writers are failing us – failing women – because they have stopped questioning, challenging and conceiving of alternatives. To prevent the loss of our hard-won rights, it is time our literature returns from its vacation from feminism and reclaims the voices it has (hopefully) temporarily lost.

Until as late as the early nineties, to be a woman writer was to be a feminist writer as well. Many famous feminists are also literary writers: Simone de Beauvoir, Germaine Greer, Gloria Steinem and, of course, Margaret Atwood. For a woman, putting pen to paper, providing a voice for the voiceless, has often been considered a radical act. Publishing, like everything outside the home, was men’s work; women who wanted to write and publish had to fight to do so: Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters and even Beatrix Potter. And if it wasn’t society stifling women writers, it was their brute husbands (Sylvia Plath) or their families. Alice Munro wrote her first stories in her laundry room as the wash ran and her children napped; Margaret Laurence wrote while her children were at school. On snow days, she resented her kids for being home. Alice Walker taught her daughter that “being a mother, raising children and running a home were a form of slavery.” For these women, marriage and motherhood were not choices – they were expectations. As Atwood says, “I was writing anyway, I was writing nevertheless, I was writing despite.” That women wrote anything at all is astonishing and inspiring.

Now, thanks to these feminists, women can choose to live whatever lives they want (in this country anyway) and write about any topic they wish, yet, increasingly, women are reverting back to marriage and motherhood (in both life and in fiction), or never emerging from girlhood. Or both. Such is the case with Rebecca Walker, Alice’s daughter, who hasn’t spoken to her mother since she herself became one and her mother disapproved. Rebecca writes that “Feminism has betrayed an entire generation of women into childlessness. It is devastating.” But why is it devastating? Why isn’t a PhD or career enough for women? Has feminism “betrayed” women, forcing them into careers when they’d be happier, as Rebecca Walker claims, just being mothers? It’s 2010. Why are women willingly choosing gender roles that already looked antiquated in 1950?

The rise of commercial ChickLit is partially to blame. Bridget Jones’ Diary was published in 1996, coincidentally around the time third-wave feminism was reaching its peak. And though I actually like Bridget Jones’ Diary, mostly because it’s funny and has a plot and sex, unlike a lot of women-authored CanLit, it begat Sex in the City (the book) a year later which eventually spawned the yummy-mommy, shopaholic pink-covered books that have spread like a rash in bookstores across North America and the UK. Titles in the Shopaholic series alone make me shudder: The Secret Dreamworld of a Shopaholic, Shopaholic Ties The Knot, Shopaholic & Sister, Shopaholic & Baby and the forthcoming Mini Shopaholic. Canada, too, has its yummy-mommy shopaholic: Rebecca Eckler, who used her accidental pregnancy and monetarily-enabled motherhood to transform herself from a mostly unknown freelance journalist to successful author by writing under the most nauseatingly-named column in all of Canadian letters: Mommy Blogger. Publishing is an industry, and ChickLit makes money. It’s not surprising, then, that sooner or later, CanLit, even highbrow, Giller-worthy Literature, would become ChickLit-ified. Not surprising, too, when all forms of media, from trashy tabloids to celebrity blogs to our national magazines and newspapers obsess over the insides of women’s uteruses. Is that a baby bump? Is she expecting (in vitro fertilized) twins? Having a baby earns a woman a lot of positive attention. As French writer Corrine Maier, author of No Kids: 40 Good Reasons Not to Have Children, says, “it’s a way to show that you are happy, that you succeed in life. It proves something. It proves that you are normal, that you do like the others.” As well, babies are used to boost flagging TV ratings and are, according to gossip blogger Elaine Lui, the ultimate whitewash. “Steal someone’s husband, or be a drug addict, then become a mother and you’re redeemed.” And, of course, often the only way a girl can finally be thought of as a woman is by having a baby.

The problem with considering motherhood a woman’s greatest accomplishment is that all of her other accomplishments pale in comparison. That feminists have been trying to convince everyone for years that women can do anything else and (or instead of) be mothers matters little in 2010 and has no bearing on our literature. Nothing else a woman does is as universally applauded as having a baby – not earning a PhD (more women attended a friend’s baby shower than her PhD defence), not becoming a lawyer (most of my lawyer friends are now stay-at-home moms), not even running for president. Just ask Hillary Clinton. While the election of Barack Obama was a milestone for African-American rights, the campaign itself proved that women’s rights are still unimportant. Gloria Steinem writing in The New York Times, observed that while Obama was “seen as unifying . . . his race [Clinton was] seen as divisive by her sex.” Because feminism “is something individual to each feminist,” Feminist A often distrusts or even hates Feminist B. Or, as Margaret Atwood explains, “The fear that dares not speak its name, for some women these days, is the fear of other women. But you aren’t supposed to talk about that: If you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all. There are many strong voices; there are many kinds of strong voices. Surely there should be room for all. Does it make sense to silence women in the name of Woman? We can’t afford this silencing, or this fear.” I know that in writing this essay I risk being accused of misogyny. But who’s misogynist? To privilege one type of woman over another, as our literature does, also silences specific women (e.g., child-free) in favour of another (e.g., mothers).

As well, the problem with reducing women to breeding stock, to not taking gender issues seriously, is that women’s rights become threatened. States (South Dakota, Mississippi, North Dakota, Nebraska, Utah) are moving once again to make abortion illegal. Our own government refuses to accept the UN’s support for world-wide reproductive rights. And when women’s groups complained, Senator Ruth told women to “shut the fuck up” without any consequence. All these issues would make for an interesting and engaging novel. Instead, women write and read stories about ye-olde pregnancy down on the farm, about widows of husbands lost on yesterday’s seas, about good houses and the good families that inhabit them.

Complaining about mothers is akin to shaking a baby. Mothers, after all, are sacred – they bore us for nine months and without mothers, well, we wouldn’t be here. But if motherhood is so sacred, why did 75% of Ann Landers’ readers once say “no” when asked whether they would choose to be mothers again? Not many mothers I’ve met love being mothers – they endure, they feel rewarded – but they’ll get extremely angry at the mere suggestion that motherhood isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Corrine Maier has been called a “monster.” After Anne Kingston’s article “The Case Against Having Kids” appeared in Maclean’s, the magazine received thousands of often cruel emails and letters accusing Kingston and those who choose to be child-free of being “disgusting,” “selfish,” “lonely,” and “bored,” whose houses are “not safe to send trick-or-treating children . . . on Halloween.” And who can forget the brouhaha generated by Barbara Kay’s honest and accurate description in The National Post of Lisa Moore’s February, a novel which privileges “an artistic, leisured rendering of memory and feeling over prole-friendly dialogue, action and, above all, plot.” February, according to Kay, is yet another example of “the unrelenting self-regard of CanLit, where it’s all about nobly suffering women or feminized men.” Though Steven Galloway and a few mommy bloggers took umbrage with Kay’s comments, Kay was bang on. The problem is not “the impact that feminism has had on the industry” as Stuart Woods said on the Quill and Quire blog, the problem is that February “is so representative of what the Canadian fiction publishing industry – itself highly feminized by comparison to 40 years ago – seems to like, and typical of what wins or is at least nominated for awards here.” Note the difference between Woods’ “feminism” and Kay’s “feminized.” The literature written by women in this country is in no way – and no longer – feminist. It is feminized. And the difference between those two words – and worlds – is vast.

To better understand the difference between feminist and feminized, let’s compare Lisa Moore’s February with her story collection Open. “Melody,” which commences Open, finds a first-person narrator accompanying her friend to an abortion clinic. It is a story about the consequences of making and not making choices – about the character Melody, who does, and the narrator who lets things happen. Compare the passive narrator’s following thoughts: “I will do whatever Brian Fiander wants and if he wants to dump me after . . . he can go right ahead.  He seems to go through girls pretty quickly and I want to be gone through” with Melody’s post-abortion words: “Not too bad, she says. She is ashen. Tears from the corner of her eyes to her ears. Sometimes you have to do things, she says.” The story flashes forward to find the now forty-something narrator widowed and regretting her decision to remarry, realizing she’s “never initiated anything in her life.” When Melody arrives to visit, the narrator tells her, “I’m married . . . I’ve messed up, Melody.” And Melody responds, “You’ll just have to do something about it.” Differentiating between active – women who do – and passive – women who have done to them – is what makes “Melody” feminist literature. The feminist movement, in all its waves, has fought to ensure that women have and can make choices. And making choices is also what drives narrative and moves plot. Adrienne Rich says, “for a character or an action to take shape, there has to be an imaginative transformation of reality which is in no way passive.” In making Melody active – and in making the narrator realize she needs to be active – Moore has written a real story with real, fully fleshed-out women characters, has properly transformed reality, which should be the goal of all fiction.

He seems to go through girls pretty quickly and I want to be gone through” with Melody’s post-abortion words: “Not too bad, she says. She is ashen. Tears from the corner of her eyes to her ears. Sometimes you have to do things, she says.” The story flashes forward to find the now forty-something narrator widowed and regretting her decision to remarry, realizing she’s “never initiated anything in her life.” When Melody arrives to visit, the narrator tells her, “I’m married . . . I’ve messed up, Melody.” And Melody responds, “You’ll just have to do something about it.” Differentiating between active – women who do – and passive – women who have done to them – is what makes “Melody” feminist literature. The feminist movement, in all its waves, has fought to ensure that women have and can make choices. And making choices is also what drives narrative and moves plot. Adrienne Rich says, “for a character or an action to take shape, there has to be an imaginative transformation of reality which is in no way passive.” In making Melody active – and in making the narrator realize she needs to be active – Moore has written a real story with real, fully fleshed-out women characters, has properly transformed reality, which should be the goal of all fiction.

With its emphasis on “womanly knowledge” and “femininity,” on placentas and grieving and remembrance, on mothers and mothering, February certainly seems gynocentric (seriously – someone should concord the novel and count the use of the word “placenta” and “blood”). But the examples I cite above – Helen’s passivity and the novel’s consequent lack of plot, her privileging of her son and dead (and therefore passive) husband over her (barely existing) three daughters, the feminized clichés (“Helen cleans the cupboards. She cleans the fridge. She listens to the radio and scrubs a pot and the yellow of her rubber glove looks weirdly yellow . . . .” “She sews wedding gowns . . . . Her sewing gives her satisfaction”) – February isn’t just unfeminist, it is actually anti-feminist. To write and publish such a novel and create such a character at a time when more women graduate from universities than men sends the message that breeding is more important than education. Take the following scene from February as proof: PhD-candidate Jane’s academic friends throw her a baby shower. Jane is pregnant with John’s baby. John is Helen’s son. Of the women at the shower, Moore writes, “They were all in their mid-thirties and most of them were childless because they’d lost themselves to academic careers.” Note how much this line echoes Rebecca Walker’s claim that women have been devastatingly betrayed into childlessness. Lost themselves? Why not found? As the holder of (almost) four university degrees, two of which are graduate degrees, I most certainly know that education has helped me find myself, not lose. Since writing Open, Moore has forgotten how “to question, to challenge, to conceive of alternatives” as Rich said. Instead, February celebrates female passivity, shows no alternatives to “mother” or “wife” when such alternatives are innumerable, and in championing passivity and old-fashioned gender roles, Moore, along with the women who champion her, twists feminism into its inverse. No wonder Canada’s Employment Insurance has maternity leave benefits but not graduate school benefits. No wonder Nancy Ruth can tell women to “shut the fuck up” and get away with it. Mainstream CanLit agrees with Senator Ruth.

A problem with such passivity is it creates victims, certainly on the page and quite possibly in life. Passive characters allow themselves to be victims. Victims in CanLit are not new; Margaret Atwood pointed out the proclivity for victim characters in 1972’s Survival. Then she argued that the two primary preoccupations with CanLit were survival and victims. Almost forty years later, despite a greater number of women writing and working in publishing, little has changed. Moore’s Helen O’Mara is a survivor (though an amputated survivor, to paraphrase Atwood, having lost a husband and living most of her life internally); her husband Cal is a victim. But Helen is also a victim because she, as Atwood says, “show[s]a marked preference for the negative”: “Helen has mastered loneliness . . . .” “[She] had died and was dead and was back in the car, a ghost, or something without musculature or bone. Something that could never move again.” Or, as Barbara Kay summarizes Helen, “Me, me, me and my extraordinary capacity for sadness.”

Mothers, in life and in fiction, are often equated with victims because of the sacrifices they feel they must endure. Education, career, sex, creativity, money, environment – all must be sacrificed for the baby, as Helen and Jane do in February, as if women don’t have a choice. The thing is, especially in North America and all over Europe, women do have a choice. In France and Russia, governments have resorted to bribing women to have babies. Italy has the second-lowest birth rate in the Western world: its state incentives aren’t incentive enough to drag women back to the bambinos. Again, this is what feminists fought for. By the time this essay is out, I’ll have just started teaching a third-year university fiction-writing workshop. My students, male and female, will have absorbed plenty of the reverence for Lisa Moore in general and this novel in particular. Why coach women toward publishing and graduate degrees when Canada’s successful women authors literally coach them towards mental suicide? “My brain went out with the placenta,” Moore writes in February. Women continue to erase their identities once they become mothers as if motherhood isn’t just motherhood but, to use Atwood, “a vestige of a vanished order which has managed to persist after its time has passed, like a primitive reptile.” Thus, Helen is doubly a victim for losing her husband and being left behind to care for their children and grandchildren, sacrificing all else in the name of the seemingly saintly but ultimately unhappy, imprisoned state of motherhood.

A CanLit character whose name alone indicates her victimhood is the utterly victimized Baby in Heather O’Neill’s Lullabies for Little Criminals. Lullabies isn’t just victim-lit, it’s victim-porn – everything bad that could happen to Baby does: dead mother, drug-addicted, abusive father, homelessness, rape, prostitution, heroin addiction, drug overdose. Though the novel spans Baby’s childhood and adolescence, Baby is in a perpetual state of juvenility – she obsesses over toys and dolls and her not-too-distant past. “I remembered this one time . . .” starts far too many sentences.  Baby is absolutely passive – instead of doing, she lets things happen to her. When her father rips up her dolls, instead of getting angry at him, she pities herself: “That doll had been like a miracle to me. It had reminded me that I’d been loved by my mother. Now I was nothing, a real nobody.” She can’t even save herself. At the end of the novel it is Jules, her father, who whisks her away from the city to a cousin in the country. On the bus from Montreal, Baby plays with the “little family of toy mice” Jules has given his teenaged daughter as a gift (even though the gift came with a tag that said “GIRL 5 and Up”) and tells Baby about her mother: “Elle etait seulment une bébé comme toi, mon amour” (she was only a baby like you, my love). Only a baby. Nothing else. The thing is, despite her name, Baby should not be a baby. Baby’s been turning tricks on the streets of Montreal. But O’Neill’s Baby doesn’t get her climactic, grown-up moment like that other famous fictional Baby, Frances “Baby” Houseman. Yes, Dirty Dancing is a Harlequin tale for the big screen, but at the end of the movie, when Johnny finds Baby at her parents’ table during the last dance of the season, recall what Johnny famously says: “Nobody puts Baby in a corner” and Baby steps onto the stage as Frances, Baby no longer. O’Neill’s Baby, however, lets everyone put her in a corner.

Baby is absolutely passive – instead of doing, she lets things happen to her. When her father rips up her dolls, instead of getting angry at him, she pities herself: “That doll had been like a miracle to me. It had reminded me that I’d been loved by my mother. Now I was nothing, a real nobody.” She can’t even save herself. At the end of the novel it is Jules, her father, who whisks her away from the city to a cousin in the country. On the bus from Montreal, Baby plays with the “little family of toy mice” Jules has given his teenaged daughter as a gift (even though the gift came with a tag that said “GIRL 5 and Up”) and tells Baby about her mother: “Elle etait seulment une bébé comme toi, mon amour” (she was only a baby like you, my love). Only a baby. Nothing else. The thing is, despite her name, Baby should not be a baby. Baby’s been turning tricks on the streets of Montreal. But O’Neill’s Baby doesn’t get her climactic, grown-up moment like that other famous fictional Baby, Frances “Baby” Houseman. Yes, Dirty Dancing is a Harlequin tale for the big screen, but at the end of the movie, when Johnny finds Baby at her parents’ table during the last dance of the season, recall what Johnny famously says: “Nobody puts Baby in a corner” and Baby steps onto the stage as Frances, Baby no longer. O’Neill’s Baby, however, lets everyone put her in a corner.

In life, of course, a woman with so many disadvantages would find it difficult to save herself and change her situation. But Lullabies is fiction, and as stated, fiction must question, challenge, and conceive of alternatives. Worse than O’Neill’s refusal to question or challenge, or conceive of alternatives is the fact that this book was chosen by the CBC as the book all Canadians should read in 2007. Should all Canadians read such an example of a negative role model? Should all Canadians celebrate the passive, victimized and self-piteous Baby? If, as Atwood claims, “a writer’s job is to tell a society not how it ought to live, but how it does live,” then what is O’Neill telling Canadians about Canadian women? That we don’t grow up, that we are content to be babies or kinderwhores or that it’s okay to be a victim.

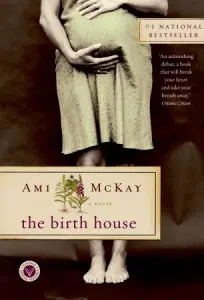

Baby isn’t just a baby through her name and (lack of) actions but also through her voice. O’Neill is not the only woman writing in Canada who is content to, as she says, “write in the voice of a child;” there is a long line of women who want to approach the microphones of literary festivals with lollipops in their mouths. Lullabies for Little Criminals, Miriam Toews’ A Complicated Kindness, Ami McKay’s The Birth House and Jessica Grant’s Come, Thou Tortoise, all suffer from “girl-voice.” Girl-voice is almost always first-person, present tense, child-like (despite the fact that the narrator is often not a child!) and throws around sentence fragments like beads at Mardi Gras. It is the same twee voice used in most YA novels and indeed, girl-voiced novels and short stories are often as simplistic and easy to read as YA (not to bash YA – YA novels almost always have a plot, unlike a lot of so-called adult CanLit). Girl-voice is cutesy and quirky and silly and saccharine, the narrative equivalent of skipping ropes and jellybeans. Girl-voice reduces the importance of such adult topics as rejecting religion, midwifery vs. hospital births, and the death of a parent. In fact, at the outset of Come, Thou Tortoise, I had a hard time believing that the narrator was not 1) a child (she’s not – she has a boyfriend) and 2) developmentally delayed (her voice sounds strikingly similar to, but not as smart as, the autistic teen who narrates The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time). Girl-voiced books are extremely popular precisely because they are simply written and easy to read – their narrators with their infantile names (Baby, Nomi Nickel, Dorrie Rare, Audrey Flowers and her pet tortoise Winnifred – who narrates portions of the novel!) are of little threat to the status quo.

The problem with the rise in popularity in girl-voiced literature is it exacerbates the perpetual adolescence craved by Baby Boomers, Gen Xers and Gen Y. Nowadays, no one wants to grow up; thirty-something women openly refer to themselves as girls, especially on blogs: BritGirl, Grumble Girl, Goofy Girl Blog, That Girl Emily, Clever Girl Goes Blog, The Everywhere Girl, Book Club Girl, Home Girl’s Book Blog. And then there are the book titles. The Girl with the Pearl Earring, The Other Boleyn Girl, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Gossip Girl, Twenties Girl, Anthropology of an American Girl, The Girl Who Fell From The Sky, Spooky Little Girl, Girl in Translation, and, for some CanCon, All the Anxious Girls on Earth, Dead Girls, The Continuity Girl, and Girl Crazy. A search through the Halifax Public Library’s catalogue for title keywords: “fiction: girl” resulted in 805 entries; title keywords, “fiction: woman” produced 470. Remember The Edible Woman? Remember The Lives of Girls and Women? Looking for The Love of a Good Woman? Probably not. Though third-wave feminists told women to reclaim whichever words and roles they want – from bitch to slut to mother to girl – the problem with a woman calling herself a girl or choosing to write and speak in girl-voice is that it is self-deprecating. She sends the message that what she has to say is immature and not to be taken seriously. She traffics in the stereotypes promoted by romantic movies, glossy magazines and dating manuals (such as The Rules) that tell her that a woman, to be truly attractive (to men, to other women and, importantly, to readers), must be “young and frivolous, almost childlike; fluffy and feminine; passive; gaily content in a world of bedroom and kitchen, sex, babies, and home.” This according to Betty Friedan, who wrote these words in 1960. Fifty years later – fifty years! – has anything changed? Let’s see: women still earn less than men; men, for the most part, even in publishing, still head up companies; and Canada ranks very low for democratic countries in electing women. Perhaps if women stopped being girls – in life and in fiction – perhaps if they finally grew up, these issues could be taken seriously and the wage gap may finally diminish.

I do disagree with Friedan’s problem with women being “gaily content in a world of . . . sex.” If third-wave feminism got anything partially right, it was in encouraging women to reclaim their sexuality. Second-wave feminism gave us the Pill, and that helped delay or eliminate motherhood all together. But second-wavers also worried that women would, in taking the Pill, more easily allow themselves to become men’s sexual objects of desire. Third-wave told women to become their own sexual objects of desire (or each others’). Suddenly pornography maybe wasn’t so bad (especially self-proclaimed, “feminist pornographers” like Tristan Taormino with their female-orgasm-aplenty porn). Then along came the Internet, and porn, for better or for worse, was everywhere. Except, quite notably, in our fiction. Thanks to Web 2.0 sites like YouPorn.com, anyone can go online and watch videos of dozens and dozens of women clearly enjoying sex and having orgasms. Yet, while both men and women enjoy sex in today’s porn, where are the female orgasms in CanLit novels written by women? Women writers, more than men, are still stuck writing two sex-and-women clichès: that sexual activity has negative consequences (think Baby’s drug addiction in Lullabies) or sex is for the sole purpose of procreating (think Dorrie Rare’s obsession with getting pregnant in The Birth House). Men in these novels are still rapists or sexually indifferent (Female orgasm? What’s that?) or Harlequin-esque, lower class saviours who come late in life (for example, Dorrie’s physically-challenged farmhand Hart – Hart! – in The Birth House and Helen O’Mara’s handyman Barry the Carpenter in February). And if there’s barely any sex in these novels, forget about orgasms. Though Helen O’Mara’s husband “made her come, and waited and made her come again” he doesn’t anymore; he’s dead (the ultimate emasculation). Note, also, how this line is completely disconnected from Helen’s body – there are innumerable ways one can make a woman come – how did Cal do it? How can readers believe that Helen truly grieves for her lost husband when Moore eliminates this detail? As well, as Ryan Bigge pointed out previously in these pages, Anne Michaels’ idea of a woman’s orgasm (in The Winter Vault) is no orgasm at all: “His hand on his wife in the place their child would some day open her, where his mouth had already so often spoken to her, as if he could take the child’s name into his mouth from her body.” Where’s her and Helen’s clitoris? Why “some day”? Why not now? Why not take her labia instead of “the child’s name into his mouth?” Wouldn’t taking the woman’s orgasm be much more enjoyable for both parties than taking some non-existent, future child’s name? As Corrine Maier puts it, “Open the nursery, close the bedroom” and “Kids are the death of desire.” Worse than Michaels’ laughably bad prose is McKay’s laughing at the female orgasm in The Birth House. Dorrie (now Dora) suffers from “neurasthenia” while her husband is away at sea. To cure her condition, she orders the “White Cross Home Vibrator” and administers it nightly. What results! It cures her insomnia, makes her less anxious, quells her loneliness! Of course the joke is that Dora, without realizing, is making herself come. It’s true a self-administered orgasm can do all those things (and so much more). What’s problematic here is that the section is written for laughs. By laughing at Dora’s silly ignorance, we laugh at her orgasm. Thus, the message is that a woman’s orgasm is funny – something to be laughed at. Orgasms for comedy are no orgasms at all (after all, a woman doesn’t need to come to get pregnant). Third-wave feminism’s encouragement to reclaim our sexuality failed. Even in the rare novels that actually do feature career women, (Leah McLaren’s The Continuity Girl and Katrina Onstad’s How Happy to Be) their jobs become secondary in the quest for sperm and baby. Today, twenty-something women still have a hard time meeting selfless lovers, and a woman can’t walk into a room at a party in a short skirt without getting the stink-eye (even at a party of English professors, many of whom teach feminist literature courses). In our fiction, sex is still bad (i.e., ruinous or at best a means to an end), while social displays of female sexual confidence are verboten.

(think Dorrie Rare’s obsession with getting pregnant in The Birth House). Men in these novels are still rapists or sexually indifferent (Female orgasm? What’s that?) or Harlequin-esque, lower class saviours who come late in life (for example, Dorrie’s physically-challenged farmhand Hart – Hart! – in The Birth House and Helen O’Mara’s handyman Barry the Carpenter in February). And if there’s barely any sex in these novels, forget about orgasms. Though Helen O’Mara’s husband “made her come, and waited and made her come again” he doesn’t anymore; he’s dead (the ultimate emasculation). Note, also, how this line is completely disconnected from Helen’s body – there are innumerable ways one can make a woman come – how did Cal do it? How can readers believe that Helen truly grieves for her lost husband when Moore eliminates this detail? As well, as Ryan Bigge pointed out previously in these pages, Anne Michaels’ idea of a woman’s orgasm (in The Winter Vault) is no orgasm at all: “His hand on his wife in the place their child would some day open her, where his mouth had already so often spoken to her, as if he could take the child’s name into his mouth from her body.” Where’s her and Helen’s clitoris? Why “some day”? Why not now? Why not take her labia instead of “the child’s name into his mouth?” Wouldn’t taking the woman’s orgasm be much more enjoyable for both parties than taking some non-existent, future child’s name? As Corrine Maier puts it, “Open the nursery, close the bedroom” and “Kids are the death of desire.” Worse than Michaels’ laughably bad prose is McKay’s laughing at the female orgasm in The Birth House. Dorrie (now Dora) suffers from “neurasthenia” while her husband is away at sea. To cure her condition, she orders the “White Cross Home Vibrator” and administers it nightly. What results! It cures her insomnia, makes her less anxious, quells her loneliness! Of course the joke is that Dora, without realizing, is making herself come. It’s true a self-administered orgasm can do all those things (and so much more). What’s problematic here is that the section is written for laughs. By laughing at Dora’s silly ignorance, we laugh at her orgasm. Thus, the message is that a woman’s orgasm is funny – something to be laughed at. Orgasms for comedy are no orgasms at all (after all, a woman doesn’t need to come to get pregnant). Third-wave feminism’s encouragement to reclaim our sexuality failed. Even in the rare novels that actually do feature career women, (Leah McLaren’s The Continuity Girl and Katrina Onstad’s How Happy to Be) their jobs become secondary in the quest for sperm and baby. Today, twenty-something women still have a hard time meeting selfless lovers, and a woman can’t walk into a room at a party in a short skirt without getting the stink-eye (even at a party of English professors, many of whom teach feminist literature courses). In our fiction, sex is still bad (i.e., ruinous or at best a means to an end), while social displays of female sexual confidence are verboten.

Perhaps if those Canadian journal issues and anthologies that claim to be devoted to sex were actually sexy, perhaps if our women writers created sexually confident, twenty-first century, adult women characters instead of babies, mothers, or grandmothers, perhaps if Lisa Moore and Dede Crane had edited a collection called Great Orgasms: Twenty-Four True Stories about Mind-Blowing Sex instead of Great Expectations: Twenty-Four True Stories about Childbirth, then perhaps I wouldn’t have had to write an essay about the disappearance of feminism from our literature or worried about the diminished status of women in our country. Wouldn’t it be great if Canadian women writers were as sex-positive as their British counterparts, who contributed to In Bed With: Unabashedly Sexy Stories? What we really need are a few more Alice Munros. Though the focus of this essay has been novels, I want to emphasize Munro because she’s a feminist, not feminized, writer. Canadian women short story writers and poets have, for the most part, kept their eyes on feminism. Because these genres are less commercial than novels, these writers aren’t pressured to sell out for sales. Alice Munro, however, is commercially successful, despite writing short stories featuring some of the most intriguing, intelligent and confident women in CanLit. That’s because Munro bridges feminist divisions – she writes about rural, small towns, about grandmothers and motherhood, about marriage and birth and family and about sex and child-free (note: not childless) couples and ageing and careers and affairs and separation and remarriage. But most importantly, Munro’s women – from young women to grandmothers – don’t just watch and wait and yearn for babies, Munro’s women do. Munro’s women actively drive plots; some of Munro’s women, gasp, dislike being mothers! Some leave their families! Some are abandoned by their daughters. And some stay and raise their kids and retire and live their lives, in the present, without yearning over the past. There are lots of grandmothers in Munro’s stories, but they live now, in our time, and don’t reminisce about stove-blacking and the croup in olden times. In fact, some of Munro’s grandmothers have sex! Or at least are sexual beings. Munro is so damned good at what she does, goes deeper into and gets more out of her characters than most writers in Canada that it is no wonder her writing appeals to such a variety of readers.

Compare the confident, active, sexual grandmother Sophie in “White Dump” to the passive, past-obsessed, asexual grandmothers in most Canadian novels. Sophie, during her regular morning lake skinny dip, has had her robe destroyed by lakeside “hippies.” She marches naked back to her cottage where her son is about to enjoy his fortieth-birthday breakfast with his family: “Sophie of course did not try to shield her breasts with an arm or place a modest hand over her private parts. She didn’t hurry past her family. She stood in the sunlight, one foot on the bottom step of the veranda – slightly increasing the intimate view they could all get of her . . . . The idea was – Sophie’s idea always was – to make her own son look foolish. To make him look a fool in front of his wife and children. Which he did . . . . That is what Sophie could do, would do, every time she got the chance.” Sophie doesn’t just sit and think – she decides and does. She does not let the hippies victimize her – she won’t even be controlled by her son, who desperately wants her to cover up. And the effect Sophie’s actions have on her daughter-in-law, Isabel, is disarming: “Isabel thought she knew what it was that had unhinged her. It was Sophie’s story. It was the idea of herself, not Sophie, walking naked out of the water towards those capering boys . . . . That made her long for, and imagine, some leaping, radical invitation. She was kindled for it.” Sophie’s actions, in turn, cause Isabel to act (Isabel has an affair and her marriage eventually ends). Munro’s women do and in their doing are feminist, not feminized.

Munro delves deeply and honestly into the multiple reasons of why women do in almost all of her stories. From “The Bear Came Over the Mountain”: “When Grant first started teaching Anglo-Saxon and Nordic Literature he got the regular sort of students in his classes. But after a few years he noticed a change. Married women started going back to school. Not with the idea of qualifying for a better job or for any job but simply to give themselves something more interesting to think about than their usual housework and hobbies. To enrich their lives. And perhaps it followed naturally that the men who taught them these things would become part of the enrichment, that these men would seem to these women more mysterious and desirable than the men they still cooked for and slept with.” For Munro, sex – and usually adulterous sex – represents or is an escape from the drudgery of marriage and motherhood. Sex = change and enlightenment. Sex is one of the easiest ways a woman can conceive of alternatives, can, as Rich says, “transcend and transform experience.” Munro’s stories are refreshingly full of sex, just as many of our lives are. The fact that CanLit women don’t write about sex, or only write about the negative or maternal consequences of sex, proves that our CanLit does not properly represent the women it claims to.

The title of Munro’s story “Differently” indicates how the author, to paraphrase Rich, actively transforms reality through imagination. The story is typically Munrovian: a married woman begins an affair that changes her life. But again, Munro’s insights are remarkable, telling, and, most important, feminist, because, as Munro writes in the story, “she knew that there [are]different ways of looking at such things.” Note Munro’s confident, adult description of her protagonist Georgia’s feelings after her first encounter with her lover: “Georgia walked home, a strengthened and lightened woman, not the least in love, favoured by the universe.” Georgia’s actions take her through Rich’s “alternatives,” transform her from housewife and mother to an other self: “And Georgia herself, watching her children on the roundabout, or feeling the excellent shape of a lemon in her hand at the supermarket, contained another woman, who only a few hours before had been whimpering and tussling on the ferns, on the sand, on the bare ground, or, during a rainstorm, in her own car – who had been driven hard and gloriously out of her mind and drifted loose and gathered her wits and made her way home again.” And then, note what Georgia thinks, waiting for her now ex-lover to call: “But it seemed that such a phone call would have given her a happiness that no look or word from her children could give her. Than anything could give her, ever again.” In these lines, in her stories, Munro does what women writers in Canada have forgotten to do: she shows us other possibilities, she lets women know that there can be and should be more to their lives than being broodmares. “How should we behave?” Raymond asks Georgia at the end of the story. “Differently,” says Georgia, wisely and accurately.

Writing this essay depressed the hell out of me – reading the novels I cite here made clear to me how far backwards women have fallen in Canada, how little women care about their rights, their time in the present, how content they are to obediently accept the subservient roles of madonna or whore. As a reader, I crave intelligent, insightful, plot-driven, well-written, funny and sexy fiction. I want the fiction I read to remind or even show me how rich and varied life is. Yet, like the sexless women in CanLit, my needs are not being met. Surely I’m not the only one who wonders why there are no stories of smart, sophisticated, urbane women or university students or twenty- or thirty-something, child-free couples (both hetereo and gay) equally navigating the ups and downs of co-habitation. That I’m dissatisfied by fiction for women is one thing; that these novels rife with stereotypes are published, celebrated, awarded, read and taught is worse. If, as Harold Bloom and others suggest, reading is a means by which we feel we are less alone, then as a woman reading in Canada, I am extremely lonely.

There’s a tiny glimmer of light at the end of this dark (vaginal) tunnel of CanLit for and by women. Authors such as Ramona Dearing (So Beautiful), Charlotte Gill (Ladykillers) and Krista Bridge (The Virgin Spy) are obviously Munro’s heirs – their writing is as smart, witty, adult and sexy as Munro’s. A reader gets this from the first sentence of Bridge’s “Cockney Sunday”: “Marriage is not for the women of Daphne’s family.” Bridge’s women don’t just have sex – they have orgasms! They are active, non-stereotypical women who “cannot tolerate sad-sacked women intent on depriving themselves of the ecstasies of the female body,” who “love . . . the act of distortion, mak[e]things appear the opposite of what they are,” who “come to see penetration as a necessary invasion, something taken masquerading as something given.” When I read these women’s stories, I want to shout, “Hooray!” These female authors, my peers as readers, writers and women, get it. They are brave enough to delve deeper, to, as Wallace Stevens said of writing, use “the imagination to press . . . back against the pressure of reality. It seems . . . to have something to do with our self-preservation; and that, no doubt, is why the expression of it, the sound of its words, helps us to live our lives.”

Nominees for Journey Prize #19, including myself, were asked to write a short explanation of why or how we wrote our stories. The explanations were to be published in the back of the annual anthology along with our biographies. With such a platform, I decided to use the opportunity not to just write about how I wrote “High-Water Mark,” (a Maritime story of the lives of girls and women) but to address the themes in the story, and address my concern, as I have in this essay, over the disappearance of feminism from our literature. I was inspired, in part, by how many young women have approached me after public readings of the story – how many come up to me alone or in small groups to thank me for getting it right. The “it” varies – some relate to working in the tourism industry, some think the drug references are cool, some had a parent die of cancer or some were also teen mothers. But overwhelmingly, they thank me for creating Ainslee, the fifteen-year-old who narrates the story. Over and over they tell me, “Ainslee is me.” They relate to her because she is not a woman of yesterday or some other time – Ainslee, like these young women, is firmly of our time, and these women at my readings are desperate to meet her.

Notably, however, McClelland & Stewart ultimately chose not to publish the very commentaries they had solicited. Apparently, for “lack of room” they were only posted on the M&S website, and the next year author explanations were discontinued. I’ll conclude with (a slightly edited version of) what I wrote:

A few years into the twenty-first century, women still earn less than men. In Canada, only 20% of the seats in Parliament are held by women. All of Canada’s premiers and big city mayors are men, and the Conservative government cut funding to the Status of Women Canada. At the bookstore, most female characters are shopaholics, prostitutes, ciphers, or yummy mommies-to-be, yet in 2003, twice as many women as men graduated from Canadian law schools. Much positive attention was given to the image of a pregnant woman on the cover of The Birth House. But look closer. This headless woman is barefoot and pregnant.

Our society’s preference for immediate gratification, not sustained efforts, is now reflected in our stories: shopping versus saving, childbirth versus childrearing. When young women see fewer and fewer examples of empowered alternatives, it’s no wonder fewer women run for public office. No wonder we still earn less than men.

As a teacher, I am increasingly alarmed by the messages our young women absorb. Yes, teenagers like Ainslee in “High-Water Mark” are angry. They are disenfranchised. But when teenagers speak, how often do we listen? The message they get, then, is to not speak, and by their twenties, many seek the comfort of established gender roles. After all, it’s easier.

Young women like Ainslee and her sister Lauren exist. They are not ciphers, they are not shopaholics. On top of their bodies they have heads, and within those heads are their voices.

—From CNQ 80, The Gender Issue (Summer/Fall 2010)