When I first read Don DeLillo’s White Noise as an over-eager third-year English major, it felt like a revelation. This was the sort of affective fiction I’d been hoping to engage with as an academic.

When I first read Don DeLillo’s White Noise as an over-eager third-year English major, it felt like a revelation. This was the sort of affective fiction I’d been hoping to engage with as an academic.

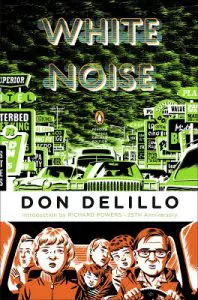

First published in 1985, White Noise remains, eight novels later, DeLillo’s most definitive work. Part wry campus novel and part grim dystopia, the novel balances humour and thoughtful observations about death, technology, and consumerism whose relevance and accuracy seems to increase with every passing year.

This is the best book I’ve ever read, I thought. And so it became the sole focus of what had previously been a postmodern-fiction mash-up of my 2010 English Honours research project. I spent every day of the final year of my undergraduate degree reading from, thinking about, or writing about White Noise. Wanting to spend more time with DeLillo’s other work, I proposed to write about trauma theory in Falling Man for my graduate-school project.

Since then, I’ve realized that my initial thoughts on White Noise were hardly original, but it remains one of my favourite novels; DeLillo, as for tens of thousands of other devoted readers, one of my literary icons. His books made me willing to think about — really think about — uncomfortable topics. Death, especially, was an unavoidable trope, yet the way he wrote about it was completely new and different to me.

My first copy of White Noise — its cover depicting two slides in an empty playground — with all of my penciled in notes and markings, did not accompany me to Edmonton, where I moved in 2011 to do my MA in English at the University of Alberta. It remained with a guy I dated briefly and had no desire to retrieve it from. I replaced it with the twenty-fifth anniversary edition, whose cover was designed by the Canadian illustrator Michael Cho.

My first copy of White Noise — its cover depicting two slides in an empty playground — with all of my penciled in notes and markings, did not accompany me to Edmonton, where I moved in 2011 to do my MA in English at the University of Alberta. It remained with a guy I dated briefly and had no desire to retrieve it from. I replaced it with the twenty-fifth anniversary edition, whose cover was designed by the Canadian illustrator Michael Cho.

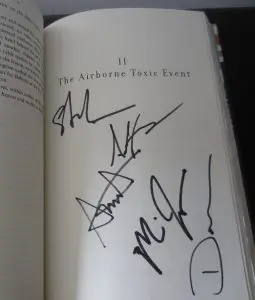

In 2014, a local radio station announced that an American indie band, The Airborne Toxic Event, would be playing at X-Fest, the station’s annual Labour Day weekend music festival. I had discovered the band while researching White Noise (their name refers to the second, and most famous, of the book’s three parts) and liked their music. When I read that they’d be signing autographs, getting them to do so in my copy of White Noise immediately crossed my mind.

“I recognize this,” the band’s lead singer Mikel Jollett said to me as he flipped through to “The Airborne Toxic Event” to sign with a black Sharpie.

“Yeah, he made all of us read it,” chimed in guitarist Steven Chen.

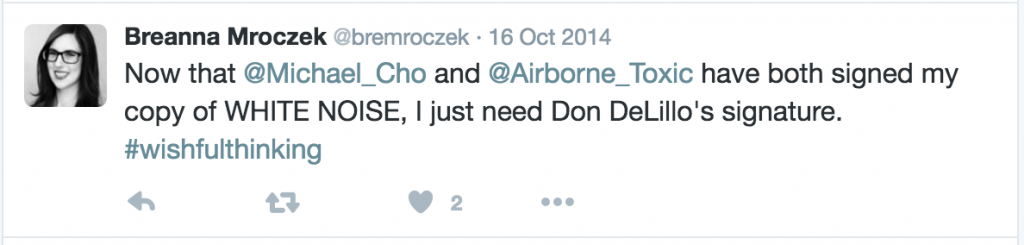

As I collected the band’s five signatures on their namesake page, Jollett and I talked about what we loved about the book (in “The Airborne Toxic Event” the main characters are evacuated from their home due to a deadly toxic spill, later becoming obsessed with their mortality). As I looked at the freshly autographed page, I was suddenly overcome with a sense of mission: I would collect as many White Noise-related signatures as possible, DeLillo’s being, of course, the most coveted. I’d once thought it unlikely that I’d ever see, let alone meet, this relatively obscure indie band with a small (and primarily American) touring schedule. Now that I had, meeting Cho and even DeLillo felt possible, too.

As I collected the band’s five signatures on their namesake page, Jollett and I talked about what we loved about the book (in “The Airborne Toxic Event” the main characters are evacuated from their home due to a deadly toxic spill, later becoming obsessed with their mortality). As I looked at the freshly autographed page, I was suddenly overcome with a sense of mission: I would collect as many White Noise-related signatures as possible, DeLillo’s being, of course, the most coveted. I’d once thought it unlikely that I’d ever see, let alone meet, this relatively obscure indie band with a small (and primarily American) touring schedule. Now that I had, meeting Cho and even DeLillo felt possible, too.

Just over a month later, I did meet Michael Cho after his appropriately titled (and fortuitous) Calgary Wordfest event, “White Noise Talks.” I approached him with both his new graphic novel, Shoplifter, and my twenty-fifth anniversary edition of White Noise. Cho told me that being asked to design the latter’s cover, and being offered flexibility in doing so, had been a career highlight, but that he never communicated directly with DeLillo. (Cho tells the story of his “dream assignment,” and the design process in detail, on his blog).

After meeting Cho I took to Twitter:

I knew it wouldn’t be easy. Notoriously private, and not reliant on public appearances to sell books, DeLillo rarely does any publicity and doesn’t use any social media. He doesn’t even have an author website or use email.

What he offers his readers are his books, supplemented by rare interviews and infrequent appearances in front of small audiences.

My opportunity came earlier this year, when I learned via social media (ironically) that DeLillo would be making an appearance in Toronto, some distance from my home in Calgary. After briefly wondering whether I should cancel an overseas trip to attend, I searched to see if he was touring elsewhere. It turned out he’d be in San Francisco on May 9 as part of the City Arts & Lectures series to promote his new novel about death and cryogenics, Zero K. Fearing the event would quickly sell out, I immediately purchased a ticket. I figured I’d deal with the logistics of getting from Calgary to San Francisco later.

I needed that autograph. DeLillo is seventy-nine, and I figured I wouldn’t have many, if any, more opportunities to see him.

My friend Kim, whom I met at the University of Calgary in our English honours course, had heard about most of the iterations of my White Noise project, including the final thesis, had since moved to Berkeley, California to work on her PhD. When I mentioned that DeLillo was giving a lecture in San Francisco, she said she’d join me and also offered to let me stay with her. I could now justify the trip as a mini-vacation where I’d get to spend time with a friend and explore an attractive city I’d never been to before.

The evening of his appearance, Kim and I made our way to the Nourse Theatre for the event, which was billed as “Don DeLillo in Conversation with Rachel Kushner.” It was to be followed by a moderated Q & A and a book-signing.

I was tempted to record DeLillo’s talk, but the venue signage warned that neither photography or recording were allowed. So I tried to soak in every story DeLillo told: that when he finished writing Libra the photo of Lee Harvey Oswald he had taped above his desk for inspiration immediately slid off the wall, that he enjoyed the work of Canadian author Michael Helm. He talked about the boxes of notes he collected about people who’ve invested in cryogenics as part of his research for Zero K.

When it was time for the Q & A, I waited hopefully for my turn among about a dozen raised hands. DeLillo answered a few questions before Kushner gestured to a young man, who gave a spiel about how much he admired DeLillo’s playwriting (Love Lies Bleeding is very good, but it usually gets lost in a shroud of Elton John-related Google searches. Is DeLillo thinking about how his work shows up in Google? Unlikely). The man concluded by asking DeLillo if he had any tips for an aspiring young playwright such as himself. More audaciously, he asked if DeLillo might critique his script one day. I was ready to write this guy and his self-centred question off when he spat out:

IWasAlsoWonderingIfBecauseYouWriteAboutDeathSoMuchAreYouAfraidOfDeath?

The room fell silent, but I think I gasped. He had asked the question I planned to ask! Most of DeLillo’s novels have characters that obsess over death; they fear it, try to understand it, and even try to prevent it with everything from secret lab pharmaceuticals to 9/11 performance art to cryogenics. I wanted to know if writing about it had helped DeLillo understand or cope with the inevitability of death.

Once Kushner relayed the question, DeLillo immediately replied that he wasn’t afraid of death, he was only afraid of leaving his wife behind to live on her own.

I feared Don DeLillo’s death, but he appeared not to. I was concerned with his professional legacy; he was concerned for his personal relationships. DeLillo’s books often seem to put forward the notion that death is a funny thing to spend our time thinking about, planning for, and trying to prevent; these appeared to be DeLillo’s own views, too.

I hadn’t been the one to get this revelation from him, but I was satisfied to have gotten the answer all the same.

The event ended with much applause, and Kim and I moved to the line for autographs with our copies of Zero K, and my own sacred copy of White Noise in hand. As the photography ban in the venue was total, I knew that a selfie with DeLillo wouldn’t be in the cards. “We were very clearly asked by DeLillo’s team to not allow photography of any kind,” said Alexandra Washkin, the production assistant at City Arts & Lectures, when I asked her about it.

In White Noise, “the most photographed barn in America” is an allegory for a place oversaturated with visual references and cultural conversations to the point where the original is all but unnecessary. It’s akin to the way millions of visitors to the Louvre snap photos of the crowds and layers of glass surrounding the Mona Lisa, but cannot photograph the unprotected painting itself. As a result, they often fail to even look at the painting with their own eyes.

“We’re not here to capture an image, we’re here to maintain one. Every photograph reinforces the aura,” says Murray, a character in White Noise, of the barn. “They are taking pictures of taking pictures.”

DeLillo thus stays away from the very spectacle he mocks. His lack of media presence — online and otherwise — has added to the sense of mystique around him.

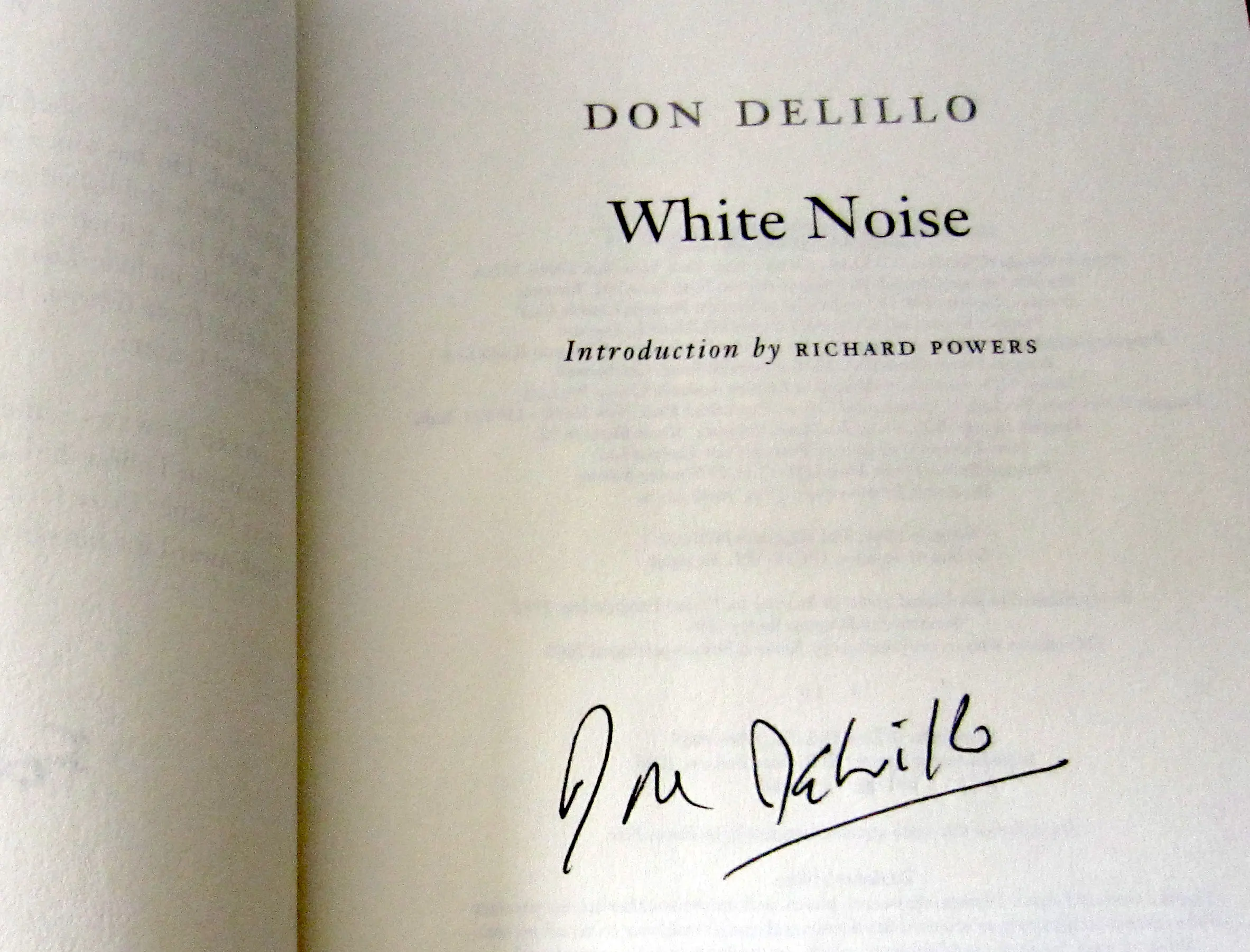

Finally, it was my turn to meet DeLillo.

“Thank you,” I said as he signed my books, then repeated it with emphasis. Thank you for affecting my life. For this autograph. For making me think. For your time tonight. For your stories. For helping the publishing industry. I must have sounded like I was thanking him for saving my life, because his pause and the tone of his you’re welcome, was kind and soft and sincere.

Yet on the walk back to the train from the Nourse Theatre, Kim and I both felt disappointed, not with the event but with having so many questions still unanswered. I wanted to know what kind of research DeLillo had done to create diverse, complex, and realistic fictional characters that interact with his interpretations of real characters (notably Lee Harvey Oswald in Libra) and actual events (notably 9/11 in Falling Man). I wanted to know his thoughts on American politics, past and present, as even though the topic is essential to most of his novels he only hints at what his true thoughts are. I wanted to know one concise idea he was trying to convey with each novel. The 90-minute talk had made me realize just how little is really known about DeLillo and his work. And unless his stories are recorded or written down as memoir, literary history will never know them.

But I had an autograph. I had his insights from that evening. That, for now, would have to be enough.

A couple of months after the event, I reached out to Michael Helm. Helm has received numerous accolades for his writing, including a Giller Prize nomination for his novel Cities of Refuge, but I couldn’t think of a more profound endorsement than DeLillo’s. I was under the — false, it turns out — impression that DeLillo and Helm had worked together closely editing one of Helm’s novels, so I was hopeful that Helm could answer some of the questions I still had about DeLillo.

Helm very kindly told me this:

A few years ago, unbeknownst to me, someone got Cities of Refuge into Don DeLillo’s hands and, by a further intervention of grace, he read it and wrote a letter to me. I’m very grateful that he’s become a friend to my novels. The only thing many of my favourite writers seem to have in common is their belief that, word to word, world to world, DeLillo’s the best. Maybe it’s no coincidence that he’s also about as generous and honourable a person as exists.

It was then I realized that perhaps I’d been asking the wrong questions.

When we get that rare chance to meet our idol, there’s always the fear that they won’t be as we hoped or imagined or, more frighteningly, that they don’t appreciate their fans with the same vehemence with which their fans idolize them. I wanted to know that DeLillo’s need for privacy and secrecy was due to personal concerns — that he wanted, perhaps, to prevent the kinds of hysterical obsession with legacy he writes about in his novels — and not to arrogance or flippant disregard.

Knowing that DeLillo was as decent and kind as I imagined him to be was, it turned out, all I really wanted to know.

—A CNQ Web Exclusive, September 2016