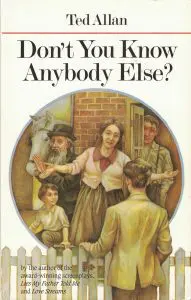

by Ted Allan

McClelland & Stewart, 1985

142 pages

2016 marked the centenary of Ted Allan’s birth. Though our lives overlapped by more than three decades, the only time I actually laid eyes on the man was at the 1993 Richler Roast. It was held at the Oval Ballroom of Montreal’s Ritz-Carlton, the same space that would be used to shoot the Panofsky wedding reception in the film of Barney’s Version. Coincidentally, it’s the very same room in which my parents’ own wedding reception was held.

Theirs was a happier marriage.

Would that I could remember Allan’s speech. The only bit – and it was a bit – that has remained with me is the end: “Mordecai,” said Allan, turning to the roastee, “do me a favour. Next time someone compliments you on Lies My Father Told Me, would you please correct them.”

Laughter.

Looking back on the decades, it’s not really so strange that I saw Allan only once. We were both Montrealers, true, but he left the city, at twenty, to fight Franco’s fascists in the Spanish Civil War. In my own youth, a friend once suggested we rent a car and drive south to join the Contras in Nicaragua. I think he was drunk. In any case, my sober observation that neither of us spoke Spanish and he had never so much as fired a gun served to dissuade.

I fired a gun – once – when I was fifteen. Scored a bullseye. Haven’t touched one since.

Allan drew on his wartime experiences in writing his 1939 debut novel, This Time a Better Earth. He was living in New York when it was published. London, Los Angeles, and Toronto followed, but Montreal would always maintain a place of prominence in his life and work. It was there that a teenaged Allan befriended Norman Bethune, the subject of The Scalpel, the Sword, his best-known book. Montreal served as the setting of Love Is a Long Shot, the disturbing pulp novel that Allan would later rewrite to win the 1985 Stephen Leacock Medal (see: CNQ 83). And, of course, it is the city of Lies My Father Told Me.

It could have taken place in no other.

Don’t You Know Anybody Else? begins with “Lies My Father Told Me,” the short story that gave birth to the film and play. It’s a strange book sold in a strange manner; McClelland & Stewart clearly hoped to capitalize on its author’s Leacock win. For reasons that will become apparent, the cover copy is worth quoting at length:

Author Ted Allan did not have to stray far from home in search of the interesting characters who were to enliven his prize-winning stories, novels, plays and films. Allan’s Montreal residence was a playhouse in which a bizarre theatrical company of family members gave a breathless non-stop performance. And for years Ted Allan has delighted the world with stories about his grandfather, a deeply religious man who could talk to God and some horses but found communication with most family members impossible; his ne’er-do-well father, a man who blew his only big payday (insurance money for being struck by a streetcar) on trying to construct electric milk boxes; and his beloved but ill-tempered mother, a woman whose tongue, in defiance of all natural law, seemed to grow sharper with use.

Because it appeared in the New Yorker (April 10, 1948), I write with some confidence that “Big Boys Shouldn’t Cry” is the best of the collection’s seventeen stories. It concerns a young boy’s attempts to get his schizophrenic father off the street and out of public view:

My father was muttering to himself. “They’re trying to get me. They’re trying to get me.”

“No, Pa,” I said, “no one is here but me.”

“I’ve got an invention that’ll make millions… Fools can’t see it…”

“Shh,” I said, “shhh…” I hated when my father talked fooling like that.

I saw a man coming towards us. “Sure, Pa,” I said, laughing. “Gee, that’s funny, Pa. That’s a swell joke all right.” I talked loud when the man passed. The man didn’t pay attention to us.

All seventeen stories in this collection are narrated by David Webber, the very same character at the centre of the reworked Love Is a Long Shot. Other high points include “The Beating” (David is bloodied by his father after he loses his younger brother at a Canadiens game), “Crazy Joe” (David befriends an unstable loner who kills himself), “One for the Little Boy” (David dreams of murdering his father and hiding his body), “The Moon to Play With” (David discovers that his jealous father killed his mother’s dog), and “What Am I Doing Christmas?” (David visits his sister in mental hospital).

Not all are so disturbing. “Looking for Bessie,” another New Yorker story (October 10, 1942), has David helping his mother in what seems a futile search for an old friend now living in the Bronx. Consider it an exception. Don’t You Know Anybody Else? is a very dark tome packaged as lite fare. I don’t see that there’s much here that delights, as the cover copy claims. Described by the latter as “the author’s collected family stories,” the book is both memoir and confession. It ends with “When Everything is Allowed,” in which David reveals his desire to make love to his dead mother and mentally-ill sister.

Don’t You Know Anybody Else? was Allan’s only short-story collection. Apparently, the title came from his father, who used the very words whenever Allan arrived for a visit. The author told the Montreal Gazette that there would be other collections from McClelland & Stewart, but these never materialized. Don’t You Know Anybody Else? holds the distinction of being his final book.

There are other stories out there; they can be found in old issues of Harper’s, New Frontier, and The New Masses. If this collection is anything to go by, they are well worth chasing down.

A worthwhile centennial project.

—From CNQ 97, Fall 2016