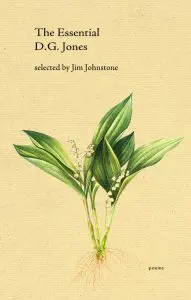

Edited by Jim Johnstone

The Porcupine’s Quill,

(64 pages)

Doug Jones died in early March last year, just a few short months before this selection of his poems was scheduled for publication. He was eighty-seven and was, according to Jim Johnstone, the book’s selector, quite ill at the end, but devoted, as he had always been, to the idea of the book. Jones had a long career. This year, 2017, will mark the sixtieth anniversary of the publication of his first book, Frost on the Sun, which Louis Dudek (who taught Jones as an undergraduate student at McGill) and Raymond Souster published through Contact Press. He was one among several young poets who were interested in myth and who were associated with Northrop Frye (rightly or wrongly), including Gwendolyn MacEwen (whose The Rising Fire was published by Contact Press in 1963) and Margaret Atwood (Contact Press issued The Circle Game. Butterfly on Rock (1970), Jones’s only critical book, is discernibly in the Frye ambit, although it is also clearly the work of a poet and not just an observer, however smart and well read. After Frost on the Sun, Jones went on to publish nine other collections of poems, as well as some important translations of Québécois poetry. His Under the Thunder the Flowers Light Up the Earth (1977) – surely the best title of any Canadian poetry book in the almost four hundred years since Robert Hayman’s Quodlibets – won the Governor General’s Award, as did Jones’s translation of Normand de Bellefeuille’s Categorics: 1, 2, and 3 (1992). With his then wife, Sheila Fischman, and a colleague, Joseph Bonenfant, Jones also co-founded Ellipse, a semi-annual journal that, unique in bilingual Canada, focused on both French and English writing, with translations of each literary work it published. Ellipse eventually migrated to New Brunswick and closed up shop in 2012, but during its run it made an essential contribution to bridging the two solitudes, from the beginning of the (first) Trudeau era. Jones would also resort to French in some of his original poems, although as a technique or a spiritual address, this idea has not found many followers, even among those poets comfortable in both languages

Jones’s M.A. thesis at Queen’s University was on Ezra Pound – its title was “The City of Dioce: the Cantos of Ezra Pound as Seen Through a Study of the Images of Building” – and he was, in some obvious ways, a poet in the mid-century modernist tradition. His training at McGill by Louis Dudek would have assured that alliance and influence. But in some essential way that is perhaps truer to his instincts, he was at heart a nature poet. He grew up in Bancroft, Ontario (David Milne territory, as “A Garland of Milne” in Under the Thunder makes clear), and had a lifelong deep and spiritual response to birds and flowers, to weather and landscape. The second and last poems in The Essential D.G. Jones are about birds, and about halfway through comes “The Pioneer as Man of Letters,” a poem so replete with the names of wildflowers as to be almost overwhelming. It is an alphabet poem, and yes, there are nods to myth during its evocative recital of “hepaticas, bright hips and haws” and “soap wort, saxifrage[and]black-eyed Susans” – a wyvern creeps in there, as well as a reference to“the serpent’s wisdom,” not to mention Ugolino, the Italian count Dante claimed ate his own children – but essentially this wonderfully fantastic poem is about a pioneer encountering the landscape, letter by letter, as it were. Of course, other poems register Jones’ captivation by myth and cultural history. “Odysseus,” for example, from The Sun is Axeman (1961), is a monologue in the voice of Odysseus based largely in the so-called Nekuia (the voyage to the underworld) in Book 11 of the Odyssey. This book contains the lines that Pound translated imperishably as “Canto 1.” Jones’s poem is not a straight translation, but it has a Homeric solidity and even grandeur that is very impressive:

What cities, and men, what girls

Might have known this face, these eyes,

What faces might my eyes have known,

Since, discarding faces, lives,

I fled across the waters red with suns

In search of one face, life, and home.

Homer’s Greek is definitely behind some of this. (Pound often quoted the line from the opening of the Odyssey that describes the hero, πολλῶν δ᾽ ἀνθρώπων ἴδενἄστεα καὶνόονἔγνω, the “cities and men” bit.) But this sort of subject matter is relatively rare in Jones’s poetry. He much prefers to look for poetry in his backyard, just as did his friend and colleague, Ralph Gustafson. (They lived on the same street in North Hatley, Quebec for many years.)

Jim Johnstone’s very judicious selection of poems from Jones’s nine collections teaches us much about the poet apart from his lifelong grounding in nature. Johnstone makes something of Jones’s transition to a postmodern poet in his excellent foreword; but while there is certainly a case to be made for that evolution, what is most striking in The Essential D.G. Jones is the technical consistency of his poetry. It is true that the earlier poems are more metrically conventional.Take, for example, the opening stanza from “Beautiful Creatures Brief as These” (such a lovely title!), with its almost metronomic pattern of stresses:

Like butterflies but lately come

From long cocoons of summer

These little girls start back to school

To swarm the sidewalks, playing-fields,

And litter air with colour.

Ibycus’s well-known spring poem surely lies somewhere behind this one – Pound made a version which Jones will have known, and so have Anne Carson and Ken Norris, memorably – but Jones’s version is very traditional in terms of metre. That traditional approach can be heard, too, in other early poems such as “Music Comes Where No Words Are,”and even in later individual lines, such as “The titans he contained in a cartouche,” from the aforementioned “A Garland of Milne.” But as he matured, Jones began to drop regular metre (though he never gave up assonance and consonance, as no poet should), and to treat the line as a different sort of unit, more architectural than metric. He also varied his tone considerably in later poems, a change that yielded lines like “Hey man, we’re on the street” or “surfing the net is no relief for the child.” (The release from initial capital letters on every line happened earlier.)

As he began to pay less attention to metre, Jones began to treat the poetic line more as a unit of syntax or even breath, much as Pound and later poets like Robert Creeley did. At the same time, he resorts frequently to enjambment to give his stanzas a flowing quality, as in “Winter Comes Hardly” (again from Under the Thunder):

a constant

grinding of small cars, trucks

made buses, the wooden benches

roofs, packed with baskets, bundles

produce, a pig in a poke, all

rattling over the pocked, serpentine

mountain roads…

He is describing winter in a hot climate in this poem, a very unCanadian winter chaos of pungent smells, tropical fruits, children, and domestic animals at large – all the very antithesis of the deadliness (“winter is Hell / for whoever has made no confession”) with which winter is usually depicted in Canadian poetry. Jones’ celebration of this sensual swirl finds its technical incarnation in those run-on lines so characteristic of this poem and others:

still

winter comes hardly here with bikinis

sprawled on the beaches, the body splayed

on the plastic deck, rocking

in a leeward breeze

Later poems are more austere in their pointing, but Jones never lost his keen eye and ear. The subject matter remained characteristic too. Jones might easily have turned into an apocalyptic eco-poet, given the widespread destruction of species, the pollution, and the threats of climate change that marked the decades of his life, even in the pastoral Eastern Townships of Quebec. But while that degradation is alluded to occasionally – he wonders how the birds manage to sleep in the glare of floodlights in a poem called “Singing Up the New Century” from Wild Asterisks in Cloud (1997) – he can still focus on “a forlorn bit of juniper / stuck in a vase” in the face of vastation (the unusual word is his) in a late, uncollected poem tellingly titled “Ideas of the End of the World.” He remained somehow cheerful to the end. While he rarely wrote about love, a Creeleyesque lyric poem like “Stumble song” (another terrific title) nimbly and convincingly encompasses the mixed blessing of an aging life, including “a dry endearment” from the loved one, and ends with the admission, not regretted, it seems, that everything is “just gently/coming apart.” Maybe so, but Doug Jones accepted that state of affairs with as much sangfroid as he’d ever had, and wrote about it (as usual) beautifully.

—From CNQ 98 (Winter 2017)