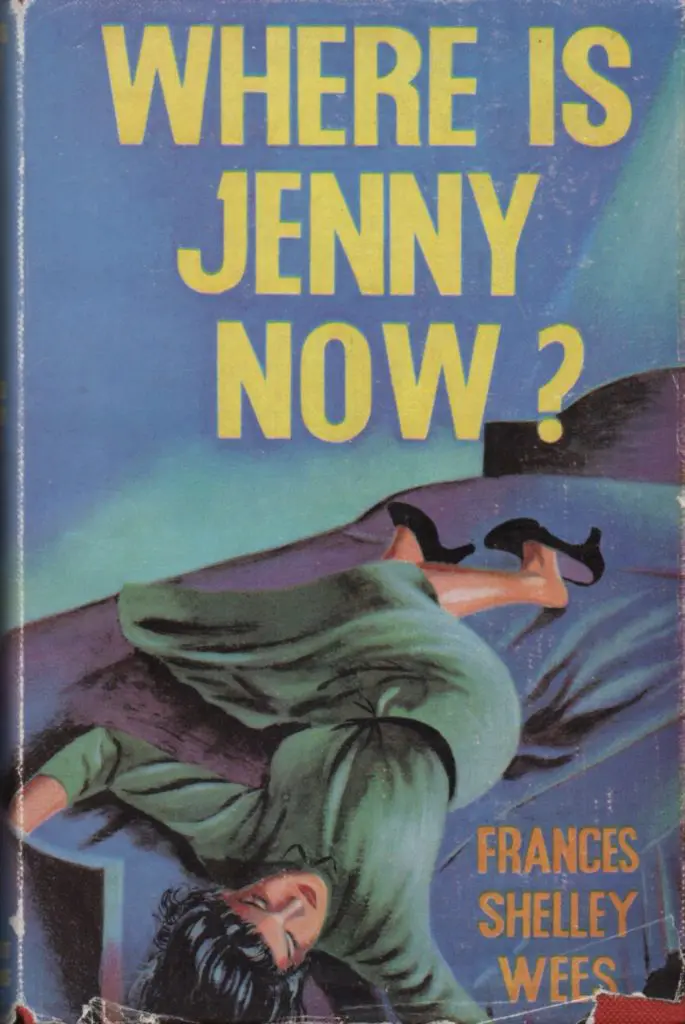

by Frances Shelley Wees

London: Herbert Jenkins, 1958

192 pages

Frances Shelley Wees’ books invite categorization. There are her romances (my favourite title is Melody Unheard), there are her textbooks (her husband was executive vice president of Gage Publishing Ltd), and there are her mysteries. Where Is Jenny Now? is a mystery, which is not to say that romance doesn’t feature or that I didn’t learn a thing or two.

Set in post-war Toronto and environs, it concerns three women: nurse Phyllis Cole, her journalist cousin Elizabeth Doane, and an eighteen-year-old domestic servant named Jenny Barnet. As the title suggests, Jenny has gone missing, her disappearance fairly coinciding with the violent murder of an employer’s inquisitive young son. Police looked for a link between the two events, but then Jenny seemed to reappear, if only briefly, working under an assumed name. They figure it must’ve been the missing domestic because a suitcase containing her clothes was left behind. Also included was a bundle of letters that revealed plans to run off with a married man.

Case closed.

Those closest to Jenny can’t accept law enforcement’s conclusion, and so urge Elizabeth to take up the chase. “It is that they do not tell the truth about her as she is, Miss Doane,” laments Jenny’s gas-monkey fiancé Chris Riker. “Jenny is a good girl. Even in the beginning they make her sound bad, like a girl who would run off for a bad reason. They cannot find her, and it is a mystery, but always underneath they make it sound that she was bad.” “She was a good girl,” echoes brother Ben Barnet. “The letter… from that Marty, the papers published parts of them. Filthy lying letters… from a married man, with two kids, him makin’ love to Jenny, talkin’ her into goin’ off to live with him, all about this new job and how he was right ready to spend lots of money on her. It sounded as if him and Jenny had been workin’ the thing out for a long time, but that just ain’t true.”

The most positive review of Where Is Jenny Now?—one sentence in length—is found in the February 14, 1958 edition of The Spectator:

Disregard the lamentable spine and dust jacket, and enjoy an extremely ingenious tale of a kidnapping in Toronto by a gang of jewel thieves, very neatly put together, not too violent, and a teasing little puzzle to the end.

I’m neutral on the spine, and quite like the dust jacket, but am much less keen on the novel itself. The problem I have is that Jenny’s disappearance is explained in the sixth of twenty-two chapters. From that point on, the reader knows precisely where Jenny is in Where Is Jenny Now?, and is left wondering how and when those searching will figure things out. The waiting is made worse by sporadic reports of what each character has learned and how they reached their conclusions.

This is not to say that this mystery isn’t gripping. What held my attention was the focus on language and class. Poor Phyllis lives in a very small house left by her late father, a talented doctor who could never bring himself to bill the less fortunate. Cousin Elizabeth, who shares the cramped space, lost her family’s money through marriage to a ne’er-do-well. As the novel progresses, Phyllis regains her social standing, and then some, when she becomes engaged to the Canadian owner of a diamond mine in South Africa. As the novel approaches the end—on the last page, in fact—it is implied that Elizabeth too will marry into wealth.

Phyllis, Elizabeth, and the men in their lives are all intelligent; not so Jenny. The best that might be said of her is that she outshines the rest of her family. She was lucky to be contracted out by AT YOUR SERVICE, MADAME (always, irritatingly, written in the upper case), an agency run by Charles Long, located in a thickly carpeted chrome-and-glass office near the corner of Bay and Bloor. Says Mr Long of the Barnet family:

“I had some doubts in engaging her… the standard of English used in her father’s home is really quite distressing. But my clients did not complain. In all other ways she was exemplary, and she tried not to speak too much. I explained to her, kindly but firmly, the impression she gave.”

The reader is later introduced to Constable Hamm, a subordinate of the extremely wealthy and extraordinarily handsome Inspector William Blake (his eyes are of “brilliant lapis lazuli”). Hamm has “a deplorable tendency to slouch,” and speaks “the speech of rural Ontario”: “This here Stoker ain’t in the mug books, sir, and his fingerprints sure ain’t on our records.”

Hamm and his fellow Metropolitan Toronto Police Services constables are next to useless. All rests on William Blake—he of the “wonderful face, open, friendly and quick”—to rescue Jenny. The heroic act occurs in the wee hours with a dozen or so ineffective Hamms in tow. No sooner is Jenny freed than Inspector Blake turns to her and says: “How about a pot of coffee, Jenny? And maybe a few sandwiches for the boys? It’s been quite a night.”

Sure, it’s not much compared to two months in captivity, fearing for your life, but for the boys it’s been quite a night.

Jenny dutifully heads upstairs, changes into her crisp, clean white uniform, pins her hair up, and heads back down to the kitchen. She may have been freed, but she knows her place.

—A CNQ Web Exclusive, July 2017