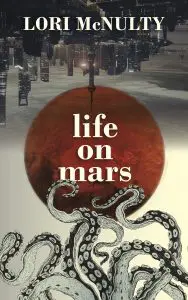

by Lori McNulty

Goose Lane Editions

296 pages

It was author Russell Smith, I think, who made an astute observation in one of his Globe and Mail columns about why novels typically sell a lot better than short story collections despite our alleged age of diminished attention spans. The point went something like this: readers come to fiction because they want to lose themselves in an expertly wrought imaginative world, even if, in the case of so-called “literary fiction,” it means they have to be extra attentive with their reading to get inside that world at the beginning of a book. Do the hard work, the theory goes, and the writer rewards you with an immersive experience. A novel is ideal because, even if it runs to five hundred pages, once you’re in, you’re in, and being there doesn’t seem so daunting. Collections of short stories, by contrast, disrupt this experience: each piece may only be fifteen or twenty pages, and when it’s over you need to reset your imaginative clock for the next one, and the next one, and the next one. Perhaps it’s because our attention spans are diminished that short-story collections are less popular than novels, not more.

Lori McNulty’s debut collection, Life on Mars, is an exemplar of this short-fiction theory. Reading her book means constantly having to situate and resituate yourself, over and over and over again. Each of these stories is its own unique and singular sphere, forged with intensity and depth and existing on what feels like a completely different plane of existence from every other story in the book. This is not to say that McNulty doesn’t deploy recurrent themes or motifs across these dozen tales—she does. They mostly involve characters best described as “misfits”; and several make allusions to the planet Mars, hence the title. Other than that, though, you’re on your own in the twelve elaborate worlds she’s created. Each of these pieces is like a novel unto itself. They are all incredibly dense, and I don’t mean that in a pejorative way. McNulty’s stories require the very best of what you’ve got in terms of attention span. This is not a book for casual readers who don’t like to be challenged.

The strongest story in the collection is also its most bizarre. “Prey” introduces us to an unlucky-in-love environmentalist named Mark who adopts a large squid, whom he names Dan, as a pet after it washes up on a beach. We learn that Mark has broken up with his wife, Rachel, and his ensuing relationship with the saucy cephalopod fills the void that the divorce—and other failures—have left in his life. As he tells us:

For weeks, I kept Dan at home in a hundred-and-seventy-gallon cylindrical acrylic tank I had rented from the aquarium shop, delivered by three giant men who positioned it on a maple pedestal in my living room. Following the advice of marine science, I kept Dan fed on a steady diet of saltwater feeder fish. His body grew twice in size. Despite an ocean of predators and our cancer chemicals, marine creatures still cling to survival. Believe me, he was suffering. I had time on my hands. Rachel was gone. Had her own needs to fill.

Mark’s reluctant ally in his efforts to pull his life back together is his former college sweetheart, Myrna, with whom he’s still friends. Unfortunately, the meeting he arranges between Myrna and Dan doesn’t go well. Dan emerges from a sink after Myrna arrives at Mark’s place and wraps a tentacle around her throat. She in turn grabs a carving knife and cuts off part of the tentacle. When Mark flips out, Myrna assures him that the limb will grow back. “That’s a sea star!” he retorts.

It’s all quite comical, but “Prey” also has moments of tender melancholy. We empathize with Mark at every step of his failure-to-launch life, and can’t help but be charmed as his devotion to the squirmy, slippery Dan borders on bromance. McNulty packs a novel’s worth of adventure in one brief story. We get a sense of Mark’s longing for Myrna, his relationship with his mother, and his desire to help save the planet. We follow him and Dan on not one but two road trips: up the California coast, and across the continent to Newfoundland.

“Prey” ’s whimsy contrasts with the seriousness of some of the other stories. Two stand out in particular. In “Monsoon Season,” a guy named Terry travels to Thailand for gender-reassignment surgery. Transforming into Jess takes a physical and emotional strain, which McNulty imposes on the page in heartbreaking detail. Jess’ encounters—with the doctors, another transsexual person looking to have her gender changed, her own mother—are described with a keen sense of quotidian and emotional accuracy. “Monsoon Season” isn’t the first Canadian short story to deal with transsexualism, but it’s notable for its thorough, and empathetic, layoung out of specificities. We get details of the physical transformation itself, the emotional fallout, and how this sort of invasive change can redraw the landscape of our most treasured relationships.

The second is “WOOF,” about a woman who casts off her life as an investment manager in a big city to get back to nature after a breast cancer diagnosis. WOOF is an acronym for “Wild Ones Over Forty,” and has a somewhat derogatory connotation (similar to MILF). As McNulty describes it:

Women who eschew social conventions. Abandon everything and book it for the airport. Outliers … The gist of it was that, unable to face their disappointing futures or corrupt world views, WOOFs seek relief in reckless adventure. They wander freely for a time, aimless as cattle, but they always make their way back.

Returning from an extended stay in the woods, the woman, Bella, gets a desperate email from her oldest friend, Cynth, asking her to come over and help her. But Bella soon realizes she’s been duped: her family and friends have instead orchestrated an elaborate intervention to stop her devolving into a WOOF. They call her acts “selfish”; accuse her of being “in a rut” and “spinning her wheels.” But McNulty’s story grapples with the age-old question: Who does my life really belong to? This piece reminded me of the award-winning novel, The Vegetarian, by Korean author Han Kang, about a woman whose abrupt decision to give up meat turns her family against her. McNulty looks at a similar subject matter here through an overtly feminist lens, and by the end of “WOOF” we find ourselves rooting for Bella as she draws a new and unorthodox map for the territory of her life.

Readers will find other gems sprinkled throughout Life on Mars. “Two Bucks from Brooklyn” has a certain Trainspotting vibe, as a crew of rough guys with weird names (e.g. Tu and Jello) get wrapped up in what appears to be a drug deal about to go very badly. “Ticker,” about a sportswriter in need of a heart transplant, is less about the titular organ itself and more about loyalty, as the narrator’s friend Aardvark tries to get him to cheat on the love of his life.

Indeed, across these twelve tales, there are very few missteps. I did find it curious that McNulty opened with what passes for the title story of the collection, “Evidence of Life on Mars.” It isn’t that this piece is weak, but it’s the weakest in the book. It tells the story of a pot-smoking dude named Mars, his brainy, put-together sister, Lizzie, their hanging-on-by-a-thread lawyer mom, and absent truck-driver dad. There’s a lot to like in this story, but it’s also marred by its protagonist’s painfully overwrought similes (“Squinty-eyed smiling, I notice the whites of her eyes look firm, like hard-boiled eggs, as if she’d been trapped in an existential windstorm”). It’s hard to discern if this is a deliberate expression of marijuana’s effects on Mars’ young brain, or just bad writing.

Overall, though, the stories in Life on Mars will take you into all the rewarding depths and complexities of a novel in just a few short pages, and you will need to take breath and reorient yourself after each one. This collection isn’t for everybody: many of its tales are elusive, elliptical, and mysterious. But those readers willing to put the effort in and have their imaginations tested will be amply rewarded.

—From CNQ 100, Fall 2017