How the Canadian Opera Company’s re-staging of “Louis Riel” continued a legacy of marginalization and forgetting

When the Canadian Opera Company restaged Harry Somers’ Louis Riel in Toronto, Ottawa and Quebec City in 2017, the production was met with a great deal of excitement and anticipation. A seemingly endless number of articles discussed the production and director Peter Hinton’s attempts to address the colonial biases embedded in the work. Indigenous and non-Indigenous academics interested in Canadian music, or in opera more generally, eagerly added their voices to the conversation.

Many of the responses were positive; in fact, one person I spoke with was told by an opera aficionado that Louis Riel was so good that it was worth flying halfway across the country to see. Other voices were more critical. In particular, some important work was done to address Somers’ appropriation of a Nisga’a lament (which Somers and librettist Mavor Moore transformed into a “Cree” lullaby) by Stó:lō musicologist Dylan Robinson who worked closely with Nisga’a performers Wal’aks Keane Tait, G̱oothl Ts’imilx (Mike Dangeli), and Sm Łoodm ’Nüüsm (Mique’l Dangeli).

Despite the widespread attention directed at the opera, much of the debate failed to adequately address why it was restaged during Canada’s sesquicentennial celebration. (Métis scholar Adam Gaudry drew some attention to this question, but the issue did not figure centrally in general discussions.) There was, furthermore, no in-depth conversation about how Métis culture was represented in the opera—surprising given that it was a major cultural production.

What follows is a series of reflections on Louis Riel, on Canada’s consistent yet ever (subtly) changing relationship with the Métis, and on the legacy of forgetting. I say reflections rather than arguments because my intention is to keep the analysis open, to urge readers to build on them, and to consider how they might be linked to the broader context of Indigenous/settler relations in the land that is now most commonly known as Canada.

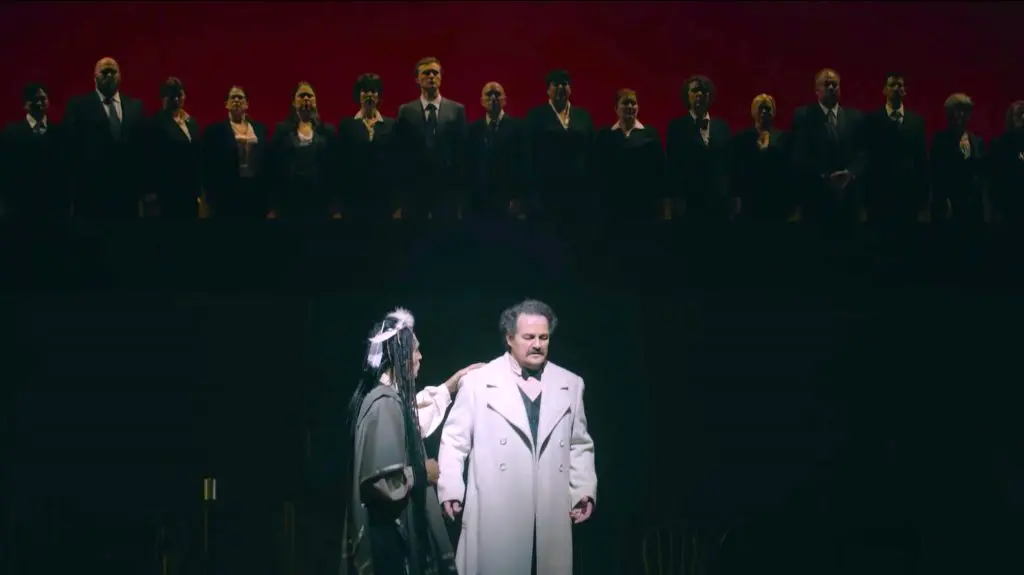

These reflections draw on my observations attending the opera in Ottawa and Toronto, as well as on critical readings of newspaper and academic articles about the opera. I also interviewed Métis attendees, and Métis performer Cole Alvis, who had a small role in the production, and was also a member of the silent chorus (which was added to the 2017 staging by Hinton).

A Curious Obsession with the Life and Death of Riel

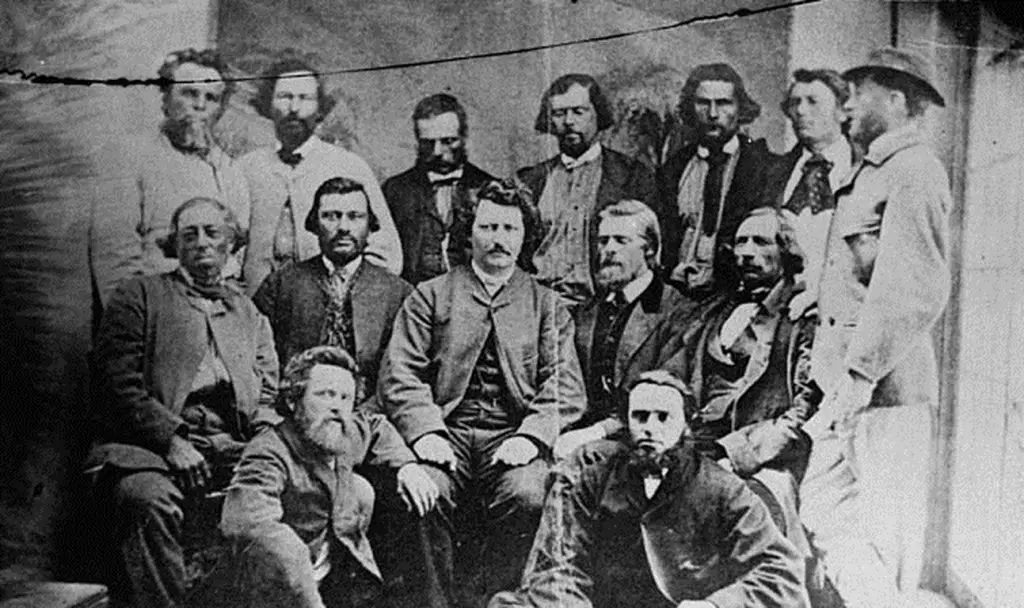

Louis Riel closes with the words “the goddamn son of a bitch is dead.” This final pronouncement is intoned by Dr. John Christian Schultz (the actor playing Schultz, that is), founder of the Canada First party, which in the late 1800s functioned as a forum for Protestant agitators in Red River. This dramatic, if rather crass end to the opera epitomizes Canada’s curious obsession with Riel—Canada’s love/hate relationship with the man and the myth.

Representations of Riel have been prolific in the arts, not just in Canada but around the world : several popular songs, at least three classical compositions, and about thirty plays have been written—largely by settler Canadians—about Louis Riel.

The opera Louis Riel is, then, part of a history of settlers representing Riel through the arts. It also embodies this love/hate relationship.

Although the opera portrays Riel as bordering on insane, other characters are arguably worse: the drunken, lying, manipulative John A. Macdonald, the childish and impulsive Thomas Scott, and the Orangemen filled with glee as they sing, “We’ll hang him up the river and he’ll roast in hell forever…” Viewers are to some extent drawn to identify with Riel despite being compelled to applaud as the opera ends—immediately after Riel is hanged—as if they were applauding his death.

Louis Riel was written to mark Canada’s centennial. While it’s remarkable that such an episode in Canadian history would be used during a time of celebration, it is also notable that Indigenous peoples were, at the time, incidental to discussions of the opera. No efforts were made to reach out to the Métis community, and one woman I spoke with noted that her mom wanted to attend the 1967 production but was unable to due to the cost. Instead, as scholars Linda and Michael Hutcheon note, the opera was positioned by the Canadian Opera Company as a “‘provocative foray into Canadian political mythology” capturing “the tragedy and high drama of an episode that almost tore the country asunder, an episode which has had important and lasting effects on the relationship between French- and English-speaking Canada.”

Indeed, the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism began in 1963, four years before the opera was created. Preliminary findings were released in 1965, the same year the Royal Union Flag was replaced. The commission’s final reports were published between 1967 and 1970.

The opera emerged, then, when the particular brand of British-Canadian nationalism that so profoundly shaped Canada’s first one hundred years was being uprooted in search of a new Canadian identity.

In the fifty years since the opera was first staged, settlers have increasingly come to see Riel, in the words of opera scholar Colleen Renihan, as an “appropriate representative of the fragmented and conflicted Canadian identity.” Famed Canadian composer R. Murray Schafer even suggested Louis Riel—the man that is—as the archetypal Canadian hero, a kind of visionary advocate of social welfare and multiculturalism, a thought echoed by philosopher John Ralston Saul in his book A Fair Country.

Perhaps it’s not surprising, given this reframing of Riel, that many critics and academics consider Louis Riel to be the great Canadian opera.

And so it was revived for Canada’s sesquicentennial celebrations, again to mark a celebration of Canada’s emergence.

Louis Riel—the opera and the man—has, then, been used at key points in Canadian history to define who we are, and the path we are on as Canadians. As scholar Sherrill Grace writes of Riel, the man, “with the irony or poetic justice of hindsight, [he]might almost be described today as speaking for all of Canada.”

Riel, the quintessential Canadian hero.

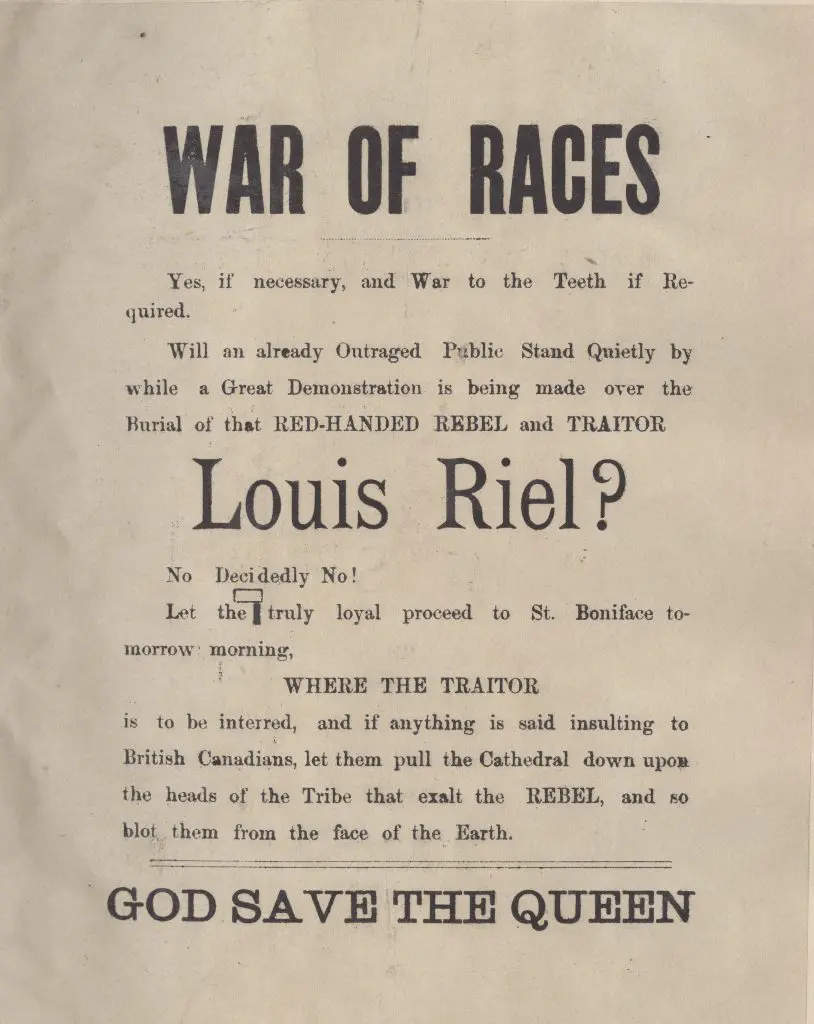

But in ending this reflection, I want to go back in time to 1885, to the eve of Riel’s burial in St. Boniface. In response to the announcement that the funeral would be held at the St. Boniface Cathedral, a flyer inciting violence against Métis people was handed out in Red River. The poster states: “Let the truly loyal proceed to St. Boniface tomorrow morning, where the traitor is to be interred, and if anything is said insulting to British Canadians, let them pull the Cathedral down upon the heads of the Tribe that exalt the rebel, and so blot them from the face of the Earth. GOD SAVE THE QUEEN.”

But in ending this reflection, I want to go back in time to 1885, to the eve of Riel’s burial in St. Boniface. In response to the announcement that the funeral would be held at the St. Boniface Cathedral, a flyer inciting violence against Métis people was handed out in Red River. The poster states: “Let the truly loyal proceed to St. Boniface tomorrow morning, where the traitor is to be interred, and if anything is said insulting to British Canadians, let them pull the Cathedral down upon the heads of the Tribe that exalt the rebel, and so blot them from the face of the Earth. GOD SAVE THE QUEEN.”

Appropriating a Little Bit of Indigeneity, But Not a Little Bit of Appropriation

One of the main points of discussion that emerged around the more recent staging of the opera Louis Riel was the issue of appropriation, in particular, the appropriation of a Nisga’a lament, which Somers and Moore transformed into a “Cree” lullaby.

The appropriated Nisga’a song was originally recorded on wax cylinder by Marius Barbeau, a well-known Canadian anthropologist. Ernest MacMillan (1893–1973), a respected Canadian composer and orchestral conductor, then transcribed the Nisga’a song from the wax cylinder recording onto paper using western musical notation.

Once transcribed, the song fell into the hands of Harry Somers, who used it in Louis Riel without knowledge of Nisga’a protocol for the song, which dictates that it should only be sung by those with hereditary rights, and only at appropriate times. As Dylan Robinson, Wal’aks Keane Tait, and Goothl Ts’imilx (Mike Dangeli) wrote in the programme notes accompanying the opera, not only do Nisga’a people consider it a legal offence to misuse the song, they believe that, if misused, it can have a negative spiritual impact on singers and listeners.

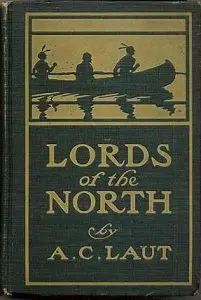

While the Nisga’a song was the most discussed, it was not the only moment of explicit appropriation in the opera. One song titled “The Buffalo Hunt” took an especially interesting path from origins to opera stage. Slated as one of only two specifically “Métis” songs in the opera, it in fact originates from a novel, Lords of the North, written in 1900 by Ontario-born author Agnes Laut (1871–1936).

While the Nisga’a song was the most discussed, it was not the only moment of explicit appropriation in the opera. One song titled “The Buffalo Hunt” took an especially interesting path from origins to opera stage. Slated as one of only two specifically “Métis” songs in the opera, it in fact originates from a novel, Lords of the North, written in 1900 by Ontario-born author Agnes Laut (1871–1936).

Lords of the North tells the story of Rufus Gillespie, who travels with a group of Northwest Company fur traders in search of a white woman and her child who have been stolen away by an “Indian.” Rufus eventually takes part in a buffalo hunt, where he is introduced to Pierre, a character described as a “half-breed rhymester” and obviously based on the Métis singer/songwriter Pierre Falcon.

This is the context in which we find the first publication of a song titled “The Buffalo Hunt,” whose lyrics are penned by Agnes Laut and voiced by her character Pierre.

Fifty-nine years later, historian Margaret MacLeod included “The Buffalo Hunt,” which she attributed to the real Métis fur trader and bard Pierre Falcon in her book Songs of Old Manitoba. The lyrics, taken word for word from Laut’s novel, are set to the song “Cécilia,” by little-known Canadian composer Jean Klinck. It was from Songs of Old Manitoba that Harry Somers took both supposedly Métis tunes for his opera.

The buffalo hunt song used in the opera was, then, an adoption of one written by settler Canadians who were trying to represent Métis people: an appropriation of an appropriation.The composer’s attempt to add a little bit of indigeneity belies a lack of attention to the source (e.g., being a nation-specific song), context (e.g., being an actual lullaby), and origin (e.g., being written by a Métis composer) of the quoted or appropriated music; all of these little bits of indigeneity, from the Nisga’a song to the buffalo-hunt song, are used to colour the opera—give it a flavour of “Indian-ness”—but do not constitute a meaningful engagement with Indigenous musics or cultures.

But to be clear: while the explicitly appropriated materials were few (limited to three songs, and some “flavour”), the opera itself is a whole lot of appropriation. As Cole Alvis told me: “the entire production is appropriation to me in that 2,000 people a show, over seven shows, 14,000 people came and thought they saw Métis culture, or think now they understand the Métis story… this is one of the things that I find quite concerning when non-Indigenous people are telling Indigenous stories. [They don’t have] the same kind of level of accountability to [the]community. I think this is where harm can really occur.”

Here I should note that the opera has never been performed in the Métis homeland (which includes the three Prairie Provinces, parts of Northwestern Ontario, the northern United States, and parts of the Northwest Territories and Northern British Columbia).

And so, while the opera explicitly appropriates only little bits of Indigenous culture, it is, once again, a whole lot of appropriation.

The Tale of a Forgotten People

The Long Journey of a Forgotten People (WLUP: 2007) by Métis historian David McNab and literary studies scholar Ute Lischke, opens with the statement “We [Métis people] are still here.” And indeed, even in 2007, when the book was written, it was a statement that needed to be made.

Before 1982, Métis people were not recognized as Indigenous people by the Canadian state. Furthermore, their presence as a living people was largely forgotten—or ignored—by settlers. It is this history of forgetting that the last line of the opera recalls: the death of Louis Riel and the supposed death of the Métis people.

Although the opera remembers the story of the resistances, it functions as a way of forgetting the Métis as a distinct people.

In my conversations with Métis attendees, I was struck by their desire to see Métis culture meaningfully and authentically represented on stage; this, when only a little dab of Métis culture was on stage.

As one Métis attendee, Marcel Larouche, told me, “When the woman was singing to her baby, in Michif, that was a very powerful moment. I think that’s what really changed the production because I’d never heard Michif in operatic form. And I just, it was magical as I said… just a wonderful experience. So that was a true… Métis experience for me.”

Another Métis attendee found the lullaby to be the opera’s most beautiful moment, a moment where Riel was a father and a husband, not just a rebel, and where Riel’s wife was a loving mother.

In the Ottawa production, this scene was changed—the cradle and baby were taken out of the scene—because that beautiful lullaby was, in fact, the stolen Nisga’a song, and the Ottawa performance a small attempt at redress.

Marcel also spoke about how people came to speak to him because he wore his Métis sash (widely recognized as a symbol of Métis identity) to the performance. He describes this as very touching, an opportunity to bring some awareness about Métis culture in a venue where patrons are typically not exposed to it. The effort that he put in to making sure his own Métis voice was part of the experience for attendees was striking.The way these Métis attendees spoke about the representation of Métis culture and family life and their efforts to reach out to attendees speaks to a profound desire to see beautiful expressions of their culture in a “high art” space; but it also highlights how Métis culture has been forgotten.

One attendee (who wished to remain anonymous) poignantly remarked that life for the Métis “wasn’t all just doom and gloom… There was lots of happiness… and dancing and jigging and… people bringing out the guitars, or the violins. There was a lot of happiness happening, and… the camaraderie of… sitting and playing cards, and just all that type of stuff… [the opera’s depiction of Métis life]seemed like a very sad existence, when I know that my family was not sad. There was a lot of happiness and lot of wonderful things going on.”

In the opera and the discussion that ensued, I was struck by how little attention was paid to the people whose story was being told, and—despite this being a major cultural production—to their culture.

In other words, Métis people are more than their story of resistance to the Canadian state.

In my conversation with Alvis, we considered whether the omission of Métis culture was good or bad: would it have been better to include more appropriation of Métis culture? Or is it better that Métis culture is omitted from the opera?

We could not come up with an answer—because both situations are far from ideal.

And so, we are left with a legacy of forgetting.

Inclusion Is an Act of Power

This fourth reflection is brief; but it gets to the structural issues at play in the recent production of Louis Riel—a production that can be seen as an attempt to salvage a settler-creation.

Inclusion is an act of power.

Cole Alvis noted that there are rules that govern the ways in which operas and other theatrical works are performed on stage. In opera, these include the convention that the score cannot be changed, and instead, changes must be limited to casting and staging. In Louis Riel, the European-Canadian “law” that holds the score as sacred was more important than Nisga’a law, and more important than Indigenous laws about community accountability.

Alvis also pointed out that it was challenging to include any Indigenous artists in the production. Those who were included were there at the insistence of the director, Peter Hinton. A white-settler Canadian had the power to decide who to include, and therefore who to exclude.

“The Goddamn [Opera] is Dead”

In the midst of all the mistakes—the missteps, the appropriation, the forgetting of the very people whose story was being told—an important shift happened within the collective consciousness of a major Canadian arts organization, a shift that ultimately marks the death of the opera Louis Riel.

When Métis artists Cole Alvis and Jani Lauzon came on board with the production, the principal roles had already been cast. The Canadian Opera Company was very proud of having an all-Canadian cast for a Canadian Opera. But they had not quite extended their vision to including Indigenous artists.

This was in part because—Alvis was told by an important figure at the Canadian Opera Company—there just aren’t any classically trained Indigenous opera singers. Alvis chuckled as he told me this, and then proceeded to talk about several Indigenous opera singers, including a mezzo-soprano who was part of the Canadian Opera Company chorus for nine years.

An opera about Métis people, written by two white men. Métis people played by white singers. Can this be fixed? Is it worth fixing?

Probably not, but some of the steps taken to lessen the opera’s colonial bias—the band-aid solutions—are worth noting: in particular, a Métis woman, Estelle Shook, was hired as assistant director, and for the first time ever the Canadian Opera Company had Indigenous performers playing Indigenous roles.

The sesquicentennial production also added a silent chorus (a work-around of the “law” that the score cannot be changed) made up of fifteen local Indigenous people. This chorus, as director Peter Hinton explained to a New York Times reporter, was present in all of the action, serving as a frame, as a mark of resistance, as a group affected by everything that happens in the storyline. As Alvis noted in an article published in Maclean’s: “I hope the audience [will]wonder what we’re thinking and what we would say if we were speaking.”

That was indeed what I was left wondering. When John Schultz intones the final words “The goddamn son of a bitch is dead,” the deafening silence that follows was marked by the presence of the silent chorus, which is collectively given, if not a voice, then at least a final bit of space in the opera. Instead of closing with the death of Riel, the opera closes with the possibilities that might follow.

And the only possibility that follows from this opera—from the conversations that emerged, from the way that it made major arts organizations aware of appropriate protocol—the only possibility and the only way forward is the death of the opera.

The attempt to address the problems inherent in Louis Riel were indeed small steps, bandages on a structurally flawed production. And it certainly was not the production that the Métis people I spoke with want for the Canadian Opera Company.

But when viewed from the starting point of pride in an all-Canadian cast, to the realization that this opera should not be produced as it was originally staged, the shift is more dramatic. And the lesson learned is that, yes, it was worth “fixing” because it led an important conversation, but it really cannot be “fixed”: the only appropriate next step for the Canadian Opera Company is an opera created by an Indigenous composer or composers, and performed (at least largely) by Indigenous singers: that is, an Indigenous-created, and Indigenous-led opera.

And so it is clear that the goddamn opera is dead.

—A CNQ Web Exclusive, January 2018