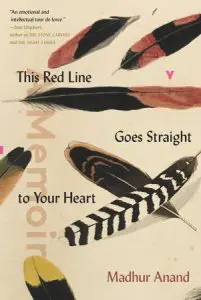

by Madhur Anand

Strange Light, 320 pages

“Some viruses have envelopes. Some letters are best left unopened. Now my mother is on the phone telling me to get my flu shot.” The virus that alters the course of life in Madhur Anand’s This Red Line Goes Straight to Your Heart is polio; her father contracts the illness as an infant and is left with a lifelong limp. His uneven gait is one of the many asymmetries that tug at the reader’s attention in this “memoir in halves.” The book itself is asymmetrical, one “half” being slightly longer than the other. The first half, titled “The First Partition,” is itself halved as Anand alternates, section by section, between her father’s and mother’s voices as we move from Partition-era India to Canada, to Toronto via Montreal and Thunder Bay. These two half-stories wrap, helix-like, around one another, providing the material for “The Second Partition,” the half of the memoir that is Anand’s own story to tell.

In 1947, the boundary known as the Radcliffe Line is drawn, dividing the British India province of Punjab into separate entities: “With the flick of a man’s wrist India ink is spilled, and there is no way to predict how much of that dark blue will become blood red,” Anand writes in her father’s voice. Against this backdrop of violence, confusion, and migration, the two young people who will go on to become Anand’s parents each achieve their successes; Anand’s father works hard, buys a scooter, studies science, while her mother works just as hard, earns certifications of her own, and becomes a teacher. With marriage, though, another asymmetry: Anand’s father immediately relocates to Canada and eventually establishes a teaching career, while his bride endures a period of purgatory—an “alternate Cinderella story” of servitude—with her new family in India before joining her husband and assuming the role of frustrated housewife in Canada.

The struggle of the newcomer is a common enough trope in Canadian literature; the false starts, disappointments, adjustments, griefs and grievances that Anand describes are hardly new terrain. What is new is Anand’s experiment with the memoir form, and her exploration of its limits: at what point does one’s parents’ story become one’s own? In the very first section of “The First Partition,” Anand’s aging mother asks, “Do you want to hear Aap beeti or Jag beeti? My version, or the version written by others?” In “The Second Partition” Anand refers to the process of researching her parents’ histories, but the stories she shares in their voices take on the mythic quality of grown-ups’ tales overheard by a child perched at the top of the stairs after bedtime.

Madhur Anand is best known to literary readers as a poet, and This Red Line Goes Straight to Your Heart is a memoir only a poet could write. There is no neat narrative trajectory; the movement is roughly linear, but the sections double back on each other as memories emerge from within retellings. Much of the story comes by way of what the author doesn’t tell us: we are given a collection of anecdotes and reflections and left to piece together three intertwined life stories from them. Anand’s prose style makes no attempt to disguise her poetic inclinations, and certain images and sequences become refrains: red lines and blue threads criss-cross the book, not just as symbols, but as material items the author encounters and remembers; words and names echo in other words and names and etymologies; asymmetries expose themselves in nature, in language, and in relationships. Anand diagnoses her fixation on pattern-finding, having read “everywhere on the internet” about apophenia, a pattern-seeking and pattern-finding disorder linked to schizophrenia, religion, and poetry.

But Anand is also a professor of ecology, and her fluency in the language of science is what truly shines here. The virus is just one of many scientific strains that shoot through Anand’s memoir; in the first pages of “The Second Partition” we encounter the physics of heartbreak, biexponential functions, Ramsey’s Theory, and breakthroughs in theoretical chemistry, which the author shares as casually and as confidently as she shares backyard observations on a nesting robin, or the memory of a favourite sweater. This reliance on language and imagery beyond the grasp of the average reader might have come off as either posturing or patronizing in less able hands, but Anand’s comfort with her material reads as so natural and sincere that the reader can’t help but follow along.

This is not to say that This Red Line Goes Straight to Your Heart is without flaw; the shifting point of view in “The First Partition” takes a while to grasp, and at times the fragmented format of “The Second Partition” pushes past the point of cohesion into what seems more like researcher’s notes than either poetry or memoir. But at its best, This Red Line Goes Straight to Your Heart is intimate, elegant, and audacious in its fundamental question of where our stories begin and end.

—From CNQ 108 (Fall/Winter 2020-2021)

We post only a small fraction of our content online. To get access to the best in criticism, reviews, and fiction, subscribe!