At fifty I wrote Marrying & Burying, a memoir. Today, twenty-seven years later, in the middle of a pandemic, I have time for a backward glance. Or a forward glance. Who can say? I’m scrubbing my hands routinely and building a coffin in the basement, hoping to ward off death.

By Ronald L. Grimes

Writing a memoir is a construction project. You convert yourself into a book. It starts out as a cabin in the woods. Then you break out in the dead of night, having lost track of who and where you are. Be-booked, you are both more and less than this self, held together between covers.

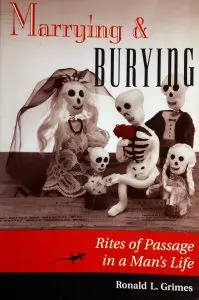

My family adorns the cover of the book. I’m the groom in the tuxedo. In real life I wouldn’t be caught dead wearing a bow tie, but weddings are weddings—even among the dead. Funerals too are for dress up, only you don’t get to dress yourself.

Susan, my wife now of decades, is veiled and bedecked for marrying. Her hair cascades, as it does in life. The Stranger, between Bryn with the rabbit pajamas and Cailleah in long braids, makes me nervous. The woman who made these Day of the Dead figures of our family said, “He’s smelling the flowers before it’s too late.”

Not long after it was published in 1995, the kids and I were visiting a bookstore and saw Marrying & Burying on the shelf.

“There I am,” Cailleah blurted, pointing to the skeleton with braids.

“That’s me!” shouted Bryn.

The woman at the till looked befuddled.

The opportunity to see yourself on the cover of a book is rare.

“Macabre,” one reader said of Marrying & Burying’s cover. True. Death is already dead; nevertheless, he is smelling the flowers.

“Macabre,” one reader said of Marrying & Burying’s cover. True. Death is already dead; nevertheless, he is smelling the flowers.

After making myself an open book in Marrying & Burying, I found it hard to write again. You only have one thing to say in life, and I’d already said it. The memoir-writer’s choices seem to be self-parody, becoming a variation on a theme in a book you yourself wrote.

I recall old memories shaking loose when I was working on a troubled section of the manuscript. I exited without saving, necessitating (after wailing and swearing), an attempt at reconstruction. The stuff was too emotionally fraught to postpone re-writing. So I began again, and within a couple of hours I had finished building a new second self.

The next day, after retrieving the first draft, I had in hand two versions of the same event. Same author; same intention. One life, two life stories.

The difference shocked me. I could no longer believe in myself.

The second book was shorter; the writing, tighter. I admired the second self; it didn’t amble. But the first book-self was vulnerable. Second-self told the truth—if not absolutely, at least directly. The first book-self was less certain what the truth was. He hadn’t written himself before, so how could he know what he was going to say?

Authors, especially of memoirs, speak with authority, or so we like to imagine. You can hear the kinship of the words: authors speak with authority. One’s authority doubles when he is his own subject matter. Who could know more about my book than I do, since I am myself and therefore an authority on it? And what greater sign of authority could there be than a book that authorizes my self?

In a phone interview, a college student asked about the photograph on page 130, the one captioned, “Grandma, the only patriarch I ever knew.”

“How,” said the voice at the other end of the phone, “did your Christian grandmother justify wearing that black dress with spiderwebs on it? I can’t believe she’d wear something like that. Or that they even made such dresses back in those days. I mean, spiders are pagan, you know. (Pause.) You didn’t have that photo touched up did you? I mean, you didn’t have the spiders added later, just for effect?”

I confessed I hadn’t noticed the webs; otherwise, I’d have pumped them for all their symbolic worth.

“What do I know?” I asked the bewildered student, “I am just the author of this book. I am the last person you should expect to speak authoritatively about it.”

That’s the thing about writing a memoir: afterward, you become merely another reader. Though you have privileged access in certain respects, in others you are especially blind. One of the reasons autobiographers write is to discover themselves. Often, they claim to be revealing themselves, but they have to discover themselves first. And whatever book-self an author reveals is surely a smokescreen hiding another self, who is even more (or less) interesting. The intention to blow away all the smoke generates a counter-intention driven by a need to add more wet wood to the fire.

For all the things readers imagine you said, or think you ought to have said, they do see things we hide from ourselves. You think you’re going make your life an open book, and maybe you do, but your life is also a boarded-up window.

You think you know yourself well enough to be aware that there is more than one of you. In my case, I hear professor-speak and father-speak, son-mode, lover-mode, kid-mode. The list is long, but at least, as author, you think you know what the list consists of. To contain it, you can play god, an omniscient narrator who can frame the whole, contain the multiplicity of actors. Let the omniscient narrator have a pleasing, well-balanced, not-too-academic-but-still-scholarly, quotable voice. I made the other choice, not of an omniscient narrator, but of I myself, playing narrator. Tom Driver’s book blurb describes that voice as “wry, sardonic, passionate, utterly unsentimental, witty, self-mocking, deeply moral, unconventionally (and uncommonly) religious.”

Memoir-selves are idiosyncratic. If they aren’t also familiar, no one will be able to make sense of them. I made myself into a book with four parts: initiating, marrying, burying, and birthing. It allowed me to track myself, using a standard map of passage rites. “Get through these four stages,” I said to myself, “and you will be a whole—albeit fictive—person.” I was enjoying imagining the book’s parts as the limbs of my body, when a fifth part emerged and ruined the symmetry. I hadn’t known anything was missing until near the end of the revisions. (Think of the possibilities and weep: self-revision = self-editing.)

It took me a long time to figure out the obvious: If you build your life story around the big moments, you miss most of your life. How many times do you birth, bury, marry, and initiate? Susan complained she hardly recognized me in the manuscript. My marrying-and-burying book-self was not my usual self; the one who fixes bikes, takes out trash, earns a living. Where were those other parts of my life?

So I added section five, practicing, to the canonical four. The practicing part isn’t about the big passages, but about small rituals, sometimes very tiny: inhaling, exhaling, inhaling; getting up, going to work, coming home. Sometimes, medium-sized rituals that last for weeks, months, seasons, and other mundane turns in time. I had invented a book-self out of a series of climactic turns with no space for ordinary time.

However much writers wish to discover their selves by making them into books, they are eventually forced to dramatize and conventionalize in order to be read. Book-selves need drama if they hope to sell, and conventions if they expect readers to believe they have real lives.

Then there are texts and images. And so arose the question of photographs, semblances of bodies. I discussed their inclusion with editors and family.

In one picture, my hair is freshly curled. I have on a dress and lipstick. I stand astride my tricycle as if expecting a horse to rescue me from mother-imposed girldom.

In one picture, my hair is freshly curled. I have on a dress and lipstick. I stand astride my tricycle as if expecting a horse to rescue me from mother-imposed girldom.

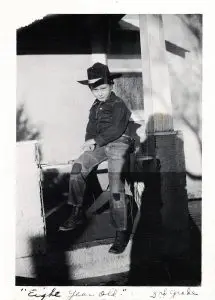

In another picture I’m a knee-patched cowboy. The list goes on: Eagle Scout with pimples, family man, scholar looking too young in cap and gown.

In another picture I’m a knee-patched cowboy. The list goes on: Eagle Scout with pimples, family man, scholar looking too young in cap and gown.

Some advised against photos. “Let readers imagine,” they counselled. In the final analysis, I was unwilling to trust myself to mere words.

When you write as many words about yourself as I did in Marrying & Burying, you can start to sound slick. You learn to mistrust this glib self. It talks back to you from the page, and, god help you, you almost fall for your own lines. You have to resist becoming a true believer in any book about yourself, especially one you’ve written. Still, it was tempting to believe that this book I’d made of myself was more myself than I am, that I should imitate it rather than it, me.

After Marrying & Burying rolled off the press in Colorado, a student in Canada got a copy before I did. “Now,” I said, “you’ll know more about me than I’ll ever know about you.” In fact, it was not he who knew more about me; it was his girlfriend. I began to appear in her dreams.

Make yourself into a fetishized object with pages and a cover, and you end up haunting your students, their girlfriends, your relatives. Eventually, you haunt yourself.

And the haunting continues. You write a book and someone in the New York Times reviews not your crafted story but your “feckless life.” How the hell would he know whether my life was feckless? There’s a difference between lives and life stories.

A student asks, “Does your wife feel exposed by your book?”

When I ask Susan, she says, “Tell that student I’d be embarrassed by her embarrassment, not by anything I do and say in your book. And please remind her that it’s your book. And life. Not mine.”

When I’m feeling low and unable to write, I sniff books. I pull one off the shelf and fan the pages. When Marrying & Burying first came in the mail, I fondled and thumbed and smelled it—almost as good as a new car. Even though Marrying & Burying’s pages have yellowed and the cover is splitting, I can still be caught reading my own book to myself. I then put the defaced icon back on the shelf with my scholarly books—the ones no one reads but which Mom kept copies of in the bookcase, alongside her home medical encyclopedia.

The year after the book was published, I was invited to the Sundance Institute as a resource person for playwrights working on plays involving ritual. The artistic director had read the demeaning New York Times review and thought I’d be good to work with. How he reached that conclusion after reading the review is beyond me.

Workshop participants (playwrights, actors, directors) insisted that I perform too, so I did a reading. I tried to draft some Sundance actors into reading, but they objected, “You, not we, are the author of the memoir.” So I had to perform myself, using Marrying & Burying as a script. Performing my ancestors—a dead son from my first marriage, my mother, my father, my grandmother—I choked up. The tears dried quickly as soon as I remembered that I had written the words. Self-consciousness, however much it apes self-knowledge, is not the same as knowing yourself. The one freezes you up; the other one frees you to attend to the world. Be careful writing yourself into a book. The act may reduce you to self-pity then steal your tears before you have a chance to enjoy them.

Memoir, for the man who would narrate his own ending, presents a problem. Originally, I said Marrying & Burying was not a book, just stray notes the kids would find after I died—a lot rambling stories about love and death, fun and failure. Maybe the ironies would make the family laugh and cry.

After I decided the notes were to become a book, the act of making myself into pages became a passage. When I would get cold feet, I’d think, “Damn it all, I’m fifty. I’ll write what I please.” Rejected fifteen times, the book was finally published by Westview Press. The opening line of the acceptance letter says, “I am very pleased, and somewhat relieved…” I was relieved because now the odds were in my favour.

The reception of the book was similarly polarized. Some reviewers really didn’t like the book: too personal, dirty laundry. If you’re not famous, who cares? Even so, I have a huge binder of personal letters written by readers who responded, often effusively, to the book. In 1996 Body Mind Spirit Magazine presented an award of excellence to Marrying & Burying.

Turning fifty, I made myself into paper, a saleable object. Most days the object was only a book, but on some days, it was a trophy, an urn, a last will and testament, a ritual object.

I wrote M&B to have conversations about births, weddings, initiations, and funerals. Some of those conversations have happened; others became impossible. However much a book is a resurrection into another kind of body, it is also a tombstone, a visit with the Stranger-sniffing-the-flower. If you think you have the last word, think again.

Ron Grimes is an American Canadian author who has written several books on ritual, including Deeply into the Bone. A recent creative nonfiction essay is “The Backsides of White Souls” published in Canadian Notes and Queries. Another essay is “Disarming Boys” published in the first issue of The Canopy Review.

—From CNQ 110 (Fall 2021/Winter 2022)

We post only a small fraction of our content online. To get access to the best in criticism, reviews, and fiction, subscribe!