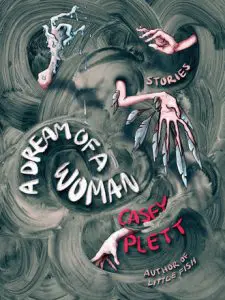

by Casey Plett

Arsenal Pulp, 256 pages.

Although the stories of A Dream of a Woman are arresting and captivating, they are disheartening too. From shorter stories “Floodway” and “Couldn’t Hear You Talk Anymore,” to the novella-length “Obsolution” (whose five discrete “chapters” are dispersed throughout the book), the portraits of transgender individuals in Canada and the US resonate because they are complex and unsparing.

In general, across seven story titles, Plett highlights a demographic on the go. Instead of upward mobility or a career-building, however, they are in search of something that remains elusive: a place that accepts them or where they feel at home. Coupled to that generalized sense of alienation, Plett documents characters whose reliance on alcohol is a daily fact or a known problem that is managed with varying degrees of success.

As they cope and quest and make amends and move on, the characters of A Dream of a Woman suggest something of a transgender Lost Generation.

Opener “Hazel & Christopher” sets the tone. Hazel describes herself as “a thirty-year-old transsexual ex-hooker in recovery” and currently inhabits a “quiet un-life” in Pilot Mound, Manitoba. Exploring Hazel’s history and outlook, Plett’s character profile is typical of the collection:

She had no idea what to do with her existence—if she had a future, or if she wanted one. In the absence of the alcohol she’d flooded herself with for half her life, her tired, newly sober body had handed her a sense of alertness she hadn’t felt since she was a teenager. At the same time, she also felt herself turning into a slug as that body barely moved. Many days, she never left the house. She slept and watched Netflix and cooked.

After a few months of watching boozy friends misbehave, Hazel begins dating. (The pairings don’t end well. “What were you doing in Montreal?” she’s asked. “Becoming a girl and a drunk.” Unsettling and incisive, Plett’s humour runs toward the mordant.)

Hazel half-believes that any period of life can bring renewal—“Can’t it? I believe in that”—even as her search for an enduring relationship reaches a bittersweet ending. Drinking again, she decides that sobriety is always waiting, “ready to come back when [she’s] ready.”

Cut from similar cloth, Gemma in “Enough Trouble” has “tapped out all the favours she can call on”: “Gemma knows she runs away easily. Her flight mechanism is primed from many angles. Chalk it up to childhood bullshit, crap with her ex, close calls in T-girl Hookerland, a blacked-out brain that has long mixed the watercolours of memory and nightmare…”

With a “dangerous love” for booze that nevertheless “turns violent despair into garden-variety sadness,” Gemma pieces together an existence “through different cities and houses and lovers, few of which ever lasted.” And Plett’s story about her latest city, house, and lover all but assures readers over a long week of quarrels, hangovers, and intriguing drunken conversations about trans identity and community (plus, in-ternet hook-ups for quick cash) that Gemma isn’t about to settle down: “She is a woman about to attempt to be alive for the millionth fucking time.” Life can bring renewal, Hazel thinks. Less hopeful and more shop-worn, Gemma opts at the moment to take a reluctant leap of faith.

Running about ninety pages, “Obsolution” is an absorbing coming-of-age narrative that follows a Portland-based university student. He tells his hard-drinking girlfriend, Iris, “I have some issues with my gender,” and the story’s five sections trace David’s evolution—a “time of never-ending new experiences” that lasts decades—as well as his active social life, including Iris and his conservative mother.

From his hand-wringing (“Was David gonna transition? Who fucking knew? Not him. It was a scary thought. For years, he’s spent nights on the internet, discovering how one went about this. And every night, he’d gone to bed blocking out more fears than he’d started with”) and trials in New York City (“This city—you give so much and get so little”), to rural Minnesota, when he’s Vera and “doing pretty good” just in time for Donald Trump’s election win, “Obsolution” presents “a melange of excitement and embattlement,” of communities and individuals emerging from isolation. The story is dense with dialogue, experiences, and perspectives, and it’s striking as a chronicle of time and place.

In “Rose City, City of Roses” Nicole reflects, “If the future holds anything normal, I could see myself becoming a good-natured old hag with a permanent seat at the bar who no one ever sees tipsy.” Based on A Dream of a Woman, no one will mistake Casey Plett for starry-eyed. Her stories hint at possibilities—of “becoming a good-natured old hag”—if only the cosmos will let it happen.

—From CNQ 110 (Fall 2021/Winter 2022)

We post only a small fraction of our content online. To get access to the best in criticism, reviews, and fiction, subscribe!