I met Milt in the mid-1970s. My wife and I had moved to Toronto in 1975 after graduating from Trent University in Peterborough. I started an M.A. in English that fall at the University of Toronto, and we found part of a house to rent in Parkdale through one of Deborah’s high school friends. The house was at 153 Cowan Avenue, midway between King and Queen Streets and just west of Dufferin Avenue. We shared the house with the friend’s grandfather, a Mr. Starkey, who was eccentric to say the least. He often roamed the property in his dressing gown, wore his grey hair in a long ponytail, and took every opportunity to regale me on the dangers of nuclear war. My piano was shipped ahead of our move from Peterborough, and when we arrived for our move-in, Mr. Starkey proudly explained that he had slept on the floor after the piano came, just in case someone broke in to steal it. It was a grand piano by the way.

At the top of Cowan Avenue where it meets Queen Street, there was a branch of the Toronto Public Library, and I became friendly with one of the librarians there, whose name I have forgotten. Eventually she invited me to give a reading at the library. In those days I was essentially a lyric poet, and I took it into my head to play harpsichord pieces—Scarlatti sonatas, I think—during intervals between reading my poems. If this sounds tweedy or ineffably high church, I can only plead a reverence back then for Basil Bunting, the English poet, who took to doing much the same thing when he gave readings of his great poem, Briggflatts, late in his life. In any case, the TPL certainly did not own a harpsichord, and I started looking for one that I could rent. A Toronto harpsichord maker, Matthew Redsell, was willing to rent me an instrument, but the cost seemed high. It was he who suggested that I speak to Milt Jewell, a Toronto artist, he explained, who had recently bought a spinet that Matthew had built. Milt was, according to him, always interested in collaboration, and might be willing to loan me his instrument. Matthew gave me his phone number.

Milt and his wife Marion lived then, as they long had, at XXV Courcelette Road, just over the city line from Toronto in the west end of Scarborough, above the water filtration plant later made famous in Canadian literature by Michael Ondaatje in his novel, In the Skin of a Lion. I give their street number in Roman numerals, because that’s the version that Milt had painted at the front of the house. It was the first thing I noticed on my initial visit, and I was charmed by it, as one might expect of a harpsichord-playing lyric poet whose M.A. thesis topic was the Cantos of Ezra Pound. Milt was then in his mid- to late thirties. He was very fit—I would later learn that he had been drafted to the Ottawa Roughriders football team out of university, though he turned down the offer—and immediately reminded me of the painter Jackson Pollock. He had been a high school history teacher, but a chance opportunity to sketch outdoors had changed his life, and he was now a full-time painter. Marion seemed kind and sweet and went out of her way to make me feel at home. On later visits, Milt always liked to say “Come early and stay late,” but even on this first encounter I was made to feel that I was an old, not a new friend. I must have met the Jewells’ three children that evening as well, Duncan, Liam, and Rachel, who were quite young then. Duncan, the eldest, was about ten years old.

I’ve forgotten what we discussed during that first visit. The harpsichord idea soon enough was forgotten, though not because Milt had any hesitation about loaning their spinet. Eventually I used a piano instead—the Parkdale branch must have owned one–and played excerpts from Hindemith’s Ludus Tonalis, which I had recently come to know. (Looking back now, that appears an even odder choice than Scarlatti.) I know that we talked about art—for some strange reason I can recall mentioning Carolee Schneeman, whose work I had seen recently in an issue of the literary magazine Caterpillar, and whose work Milt knew about—and we probably talked about music too– music, art, and family being always the main subjects of conversation whenever we would see one another in the years to come. Soon enough I started to visit Milt at his downtown studio. Back then he was a determined minimalist painter and showed at the ACT Gallery on Wellington Street, where friends and fellow painters like Ric Evans and Robert Jacks also had exhibitions. I’ve forgotten where Milt’s studio was in the mid-1970s, but I do remember then, as later, how almost overwhelming it was to be there as a writer. Writers require little more than a desk in a corner, a notebook, and a pen. Here was a large, dedicated space full of equipment and supplies and books, with art and other things pinned up on the wall, and music playing almost constantly from a tape deck. Milt was making stark, rather scary pieces back then shaped like holes punched in a wall, whose surfaces consisted of evenly applied materials like iron filings and cat litter. It was an art entirely devoid of image and unlike anything I had ever seen.

The music was unlike anything I’d ever heard too. I was well educated in conventional classical music and had even started around that time to listen to Schoenberg, Webern, Boulez, Jean Barraqué and other composers. I was spending a lot of time at the University of Toronto’s Music Library in an effort to learn more about “modern” music. I remember going in once just after the library opened in the morning and asking for Schoenberg’s opera, Moses und Aaron. The librarian looked at me and said, “Really? Before breakfast?” But Schoenberg was as nothing compared to what I heard in Milt’s studio. There was Einstein on the Beach for a start—though I see that the Tomato Records recording which Milt owned was released in 1979, so that was a little later. Milt also possessed recordings of later Glass pieces such as The Photographer and Koyaanisqatsi. There was Frederic Rzewski too. Not in the studio but in his attic room at home, Milt played Coming Together for me, the recording from 1973 with Steve Ben Israel as the speaker. It was, again, overwhelming: strange, compelling music. And then there was The People United Will Never Be Defeated in the first recording by Ursula Oppens. It was released in 1978, and after hearing it once in Milt’s studio, I asked to borrow it. I listened to it constantly for weeks, and when Marion later bought the published score, I borrowed that too and tried to play sections on my piano. The piece remains to this day deeply etched in my musical memory, and I think of it as one of the masterpieces of post-war American music. In the 1980s, the four of us—Milt, Marion, Deborah and I—heard Rzewski perform his Antigone-Legend at the University of Toronto’s Edward Johnson Music Building, and that work too became an obsession when, much later, I found a recording. There were other pieces too, music that Milt introduced me to that became touchstones: Tom Johnson’s An Hour for Piano, for example, and Kevin Volens’ string quartet called White Man Sleeps; Colin McPhee’s Tabuh-Tabuhan and his wonderful Balinese Ceremonial Music; Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians, which we heard performed live by Reich’s ensemble; Rzewski’s amazing Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues; David Jaeger’s Favour, written for the violist Rifka Golani-Erdesh, as she was then; and much more. I don’t know how exactly Milt came to be so passionate about contemporary music, but when we met he was already a devoted listener to the CBC new music programme, Two New Hours. The producer of that show, which ran weekly on Sunday nights, was the composer David Jaeger, with whom Milt was already friends and to whom he introduced us. David and his wife Sally became good friends too.

Milt and Marion were also deeply interested in Baroque music and especially in the recorder. Deborah played the recorder as well, and we had many after-dinner musical evenings in Toronto and elsewhere with me at the piano or spinet, and the other three forming a recorder choir. At some point Milt even bought a bass recorder, so that the choir would be perfectly balanced: soprano, alto, and bass. We played music by Handel, Telemann, and Bach, but also by lesser known composers such as Jean-Baptiste Loeillet, Benedetto Marcello, Charles Dieupart and others. It was all for fun and never for performance before an audience.

I’m pretty certain that Milt did not like jazz, and he disliked most pop music too. But musically he had one or two party-tricks up his sleeve. Once at the Jewells’ house he sang “The Ballad of the Frozen Logger” a capella. That’s a song about a lumberjack who likes to stir his coffee with his thumb. On second thought, perhaps it was at our house in Hamilton where Milt performed, as I feel sure that the writer Elizabeth Smart was with us that evening. She had come to Hamilton to give a reading at McMaster University. Milt would also occasionally recite from memory some of the verse in Paul Hiebert’s hilarious novel Sarah Binks, the “Sweet Songstress of Saskatchewan.” This bit was a favourite:

Oh calf, that gambolled by my door,

Who made me rich who now am poor,

That licked my hand with milk bespread,

Oh calf, calf! Art dead, art dead?

When Milt and I first met, I had published nothing and was a poet only by aspiration. He was one of the people in the 1970s who encouraged me in my writing, and we had been friends for only a couple of years when he suggested that we do a book together. He’d given me a modest watercolour—my son Jesse owns it now—that provoked a small, descriptive poem of fourteen lines. From that unprepossessing start grew a series of twelve lyric poems. I was reading the Presocratic philosophers at the time, and the twelve poems incorporated bits and pieces from the fragments of Heraclitus, whose philosophy of flux even now seems to me as relevant as when he was writing, 2,500 years ago. Milt produced twelve drawings that spoke obliquely or geometrically to the poems, though like the rest of his work at the time they contained little in the way of imagery and owed more to Sol Le Witt than to Picasso. I think Milt paid to have 500 copies of our book printed at a fast-print place on King Street West, probably near his studio, and we bestowed on it the minimalist title 12 Poems 12 Drawings. The address on King Street is now occupied by—what else?—condos. A print-run of 500 copies was probably 450 too many; decades later Milt still had a stash in the basement of his house in Campbellford, where he and Marion moved after she retired from medicine in 2000. But I was extremely happy with the book and mostly gave it away to friends. It had, I feel sure, absolutely no public reception and predictably no effect on the literary world in Canada. But it was my first book, and having a collaborator made me feel like an aesthetic grown-up. Milt used one of the poems on a poster he created for an exhibition of his held at Factory 77, a short-lived gallery established in an old carpet factory on a small street near where we were living in Parkdale.

Deborah and I moved from Toronto to Hamilton in 1979, and our daughter, Thera Emily, was born on December 24, 1980. It was Milt’s birthday too, and as a result, he always jokingly called her Thera Miltonia. From 1988 to 1996 we lived in Montreal, where we moved not long after a year’s sabbatical in the south of France. Milt photographed me one day at a nude beach on the Mediterranean Sea, a photograph that he later used as the basis for a painting (“Poet By the Sea”) that was reproduced on the front wrapper of my book Visible Stars, my first selected poems. We saw less of Milt and Marion after my graduate school studies came to an end, though there were always visits back and forth when it was possible. Milt and I somehow found occasions to work together on a series of monoprints that combined his imagery (he had by then returned to imagery) and my texts. I lettered the texts directly on the paper with stamps from an old children’s lettering set. It was more than a little nerve-wracking, since a mistake could not be corrected. One of these, a half-erased nude executed on beautiful grey hand-made paper from the Papeterie Saint-Armand in Montreal, was used much later for the front cover of the fifth book of my long poem, The Invisible World Is in Decline, which ECW Press published in 2000. That book contained two sections that came directly out of my friendship with Milt. Polyphonic Windows, as I explained in a note in the book, began as a series of short prose texts that I composed in Milt’s last studio at 30 Duncan Street in Toronto, the word “polyphonic” evoking Terry Riley’s Salomé Dances for Peace which Milt was playing on the tape deck when I was there for a visit. “Nine Encaustic Harpsichords” was meant to celebrate an exhibition that Milt had at Painted City Gallery in Toronto in 1998—Milt had it printed as a large broadside—and “A Room Full of Jewels,” the second of “Two Poems for Milt Jewell,” was a poetic description of the studio where I wrote in the backyard of our house in Santa Monica, and where I’d hung a number of Milt’s prints. I still love those brief prose poems, which are a bit crazy to say the least: one invokes “millions of nipples” and another “the great ugly wondrous rex tremendae maiestatis,” words that somehow collocate sex and a section of the Mozart Requiem.

During the years when we lived in Los Angeles, after 1996, we saw Milt and Marion once in California and occasionally in Campbellford. My son, Jesse, remembers fondly playing croquet on the big lawn next to Milt’s studio, which had been built originally as a three-car garage and which was a decisive factor in Milt and Marion’s decision to buy the house. It was situated on a large piece of land—thirty-five acres, I think—and we often went for long walks, winter and summer. Milt was an excellent naturalist, among his many other qualities, and knew not only wildflowers, but trees and grasses and ferns too. It was always a pleasure to join him on a hike. (Milt loved to berate me for my ignorance about wildflowers. Poets, he would say with a laugh, ought to know about flowers! It was an ignorance which I have corrected only recently.) The living room of the house had a thirty-foot ceiling, and that was where we played chamber music.

In the studio we went on listening to music, and on each visit, Milt would show me his new work. By then he was regularly producing encaustic paintings—big pieces that were usually based on photographs that he would project onto a blank canvas and then paint using a combination of colour and wax. That first version would then be transferred to a second canvas using a conventional clothes iron, with the result that there were frequently two distinct versions of an image. He would often letter a poem of mine over the image. In his sixties and seventies Milt loved most to produce paintings that combined nature and culture quite literally: a swamp or riverscape might have a stylized portrait of one of his culture heroes superimposed on it—Glenn Gould or Paul-Émile Borduas or Jean Cocteau. A rhinoceros (Milt admired Dr. Ferron and his satirical political party) might be painted athwart an urban landscape or standing near the Jacques Cartier Bridge. A ballet dancer might be caught en pointe among trees and wildflowers. I don’t believe that Milt thought that there was anything essentially different between nature and culture. He loved ferns and he loved Morton Feldman’s Rothko Chapel, and what, in a sense, was the difference? They both gave pleasure, and they were both incontrovertibly masterpieces. It was all a grand continuum for him, though somehow I doubt that he would have used the word “continuum.”

I knew Milt for something like forty-five years. He was rarely sullen and almost never angry, at least in my presence. He got on well with everyone, smiled almost constantly, and was interested in almost everything and everyone. He was not voluble, but he always knew what to say to buck you up, to encourage you in your own work. I imagine that he felt neglected or passed over sometimes as an artist, but he never let on to me. He just went on working, even after the move to rural Ontario when he lost the mutual esteem society that the studio at 30 Duncan Street represented, with painter friends like Jaan Poldaas and Ric Evans and Jack Brown just down the hall. He and Jaan used to race to see who could finish the Globe and Mail cryptic crossword puzzle first. On most visits to Milt’s studio, he would lead me on a quick tour of his friends’ spaces. Ric Evans and I eventually undertook a couple of collaborations, which have seemingly disappeared. They all liked to meet for drinks at the nearby Cameron House on Queen Street, where Milt showed his work on occasion. Never much of a drinker, Milt was nevertheless clearly one of the “gang,” something I envied as I also envied the working space of a studio, the place dedicated to work and play and psychologically far away from kids and kitchens and lawns waiting to be mowed. Milt’s final studio on the Campbellford property had the same feel, but it was much more isolated. That felt to me like a big change, and perhaps not for the better. He continued to work until almost the end, the moment when dementia started to become problematic, and he was moved into a care home near Cambridge, where his son Liam and his family lived. It all happened very suddenly, and I feel sure that the change was a difficult one for Milt, though on the few times when I visited him there, he certainly did not complain.

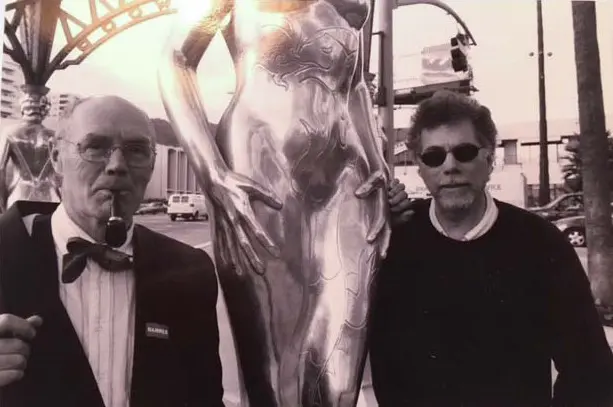

Milt eventually was given an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, something I learned only by noticing his wristband on a visit to the Cambridge care home. David and Sally Jaeger and I drove there twice to see Milt. He seemed to recognize us, and as always, despite his circumstances, he rarely had anything but a smile on his face. One time we all went for a long walk, something that gave Milt pleasure. He was not painting, but he seemed happy enough in his new residence. It was not like him to complain in any case. When Covid-19 became a pandemic and the old age homes were particularly hard hit, visits to Milt were no longer possible. I saw him last on his eightieth birthday, when Liam brought him to Toronto, before Covid, and we had lunch with David and Sally at their house in Riverdale. Milt loved to sport bowties, and for his birthday I gave him a new one. I hope he wore it. Milt affected a kind of clochard chic, with clothes mostly bought at the Sally Ann. He pulled it off sublimely.

I don’t know much about Milt’s final days and weeks, after he was admitted to hospital with what initially was diagnosed as a UTI. His health went downhill quickly, but I wasn’t really prepared for the phone call from Duncan on November 28, when I learned that he had died, still in the hospital. Covid made a visit impossible, and I only hope he had someone there with him when he lost consciousness. He was my oldest friend, and while I have some of his wonderful paintings hanging on my walls, these days they just make me sad. Eventually they will make me smile again, a bit seraphically perhaps, like Milt always smiled.

—A CNQ Web Exclusive, October 2022

We post only a small fraction of our content online. To get access to the best in criticism, reviews, and fiction, subscribe!