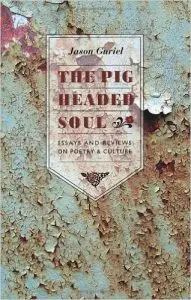

Essays and Reviews on Poetry and Culture

Jason Guriel

The Porcupine’s Quill, 2013

208 pages

In his introduction to a selection of the poetry of Rudyard Kipling, T.S. Eliot once opined that there were three kinds of poems: good, bad and good-bad. Good-bad was a category which allowed the Possum to think more or less kindly of the poetry of someone so obviously unlikely to appeal to his aesthetic principles as Kipling, who was clearly not High Church, not remotely interested in the serious poets who Eliot felt were the masters (Dante, Milton, Donne et al.), and who did not really care about Culture with a capital C. The poet of Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats nevertheless had to make room in his canonical dining-room for a chair to be occupied by someone like Kipling, a rhymester who had smarts and a musical instinct of a sort. It is rather heart-warming to watch the Highest-Culture Poet of the century make a space at his table for a bumbler like Kipling.

Jason Guriel, a thirty-five-year-old poet and critic based in Toronto who has made a name for himself as a balls-out reviewer, likes to quote Eliot and has an Eliotian degree of condescension that allows him to say some nice things about Charles Bernstein or Anne Carson, for example, while on the whole restricting his praise to poets who fall into the New Formalism camp. He loves alliteration and rhyme. He likes his poetry left-justified, with each line capitalized (the latter bestows dignity, he thinks). He admires poets, like Eric Ormsby, who do not publish too often or too much. He writes and publishes an essay on Kay Ryan that imagines a time twenty-five years from now when critics will speak of the Age of Ryan, as though she will dominate the writing of poetry for many years to come after 2010, and acolytes will publish anorexic poems on the Ryan model in magazines and blogs and every scrap of verse she has ever committed to print will command reverence. He is equally keen about the poetry of Daryl Hine and George Johnston, Canadian poets who to most critics have always seemed determinately marginal. Hine left Canada early on and was a species of New Formalist avant la lettre, while Johnston was simply an out-of-the-temper-of-the-times poet who also had a good reputation as a translator (of Icelandic sagas) and whose most famous poem, “On the Periphery,” made it into secondary-school anthologies and thereby had an outsize renown. These two were not poets who meant much during the 1960s and 1970s when Canadian nationalism was the dominant and reigning aesthetic, nor have their reputations or influence grown markedly in the post-nationalist phase of CanLit. In any case, Guriel admires their work, as he also admires the poetry of Dorothy Parker. The Parker review-essay, entitled “Perfect Contempt,” is one of the best in his book, and that is slightly disconcerting to say the least.

Book reviewing in Canada has long been a tough genre. The literary world being as small as it, and the likelihood of the author whom one reviews badly today sitting on a Canada Council committee adjudicating one’s grant application tomorrow has given most reviewers, especially poetry reviewers, a fatal case of punch-pulling. There are few literary journalists who are not also poets or novelists and who therefore have a hard time avoiding assignments to review friends’ and colleagues’ new books; and by and large Canadians’ reputation for pleasantness restricts much reviewing to the “if you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all” category. This is patently not the case with Jason Guriel. He revels in rejection and loves to deflate. He also writes well, for the most part, and comes up with zingers again and again. Of course there is a danger in the magisterial bon mot of seeming to emulate the great Greta Garbo, whose self-appraisal was “Deep down, I’m shallow,” and of thereby treating the book or poet under review as a mere pretext for sprezzatura, a word Guriel is very fond of. He quotes with approval Oscar Wilde’s aphorism that art is too important to be taken seriously, and lists as his literary models writers like William Logan, Carmine Starnino and others who are well known as self-styled debunkers and determined straight-shooters. Above all he thinks that the function of poetry, indeed of all art, is to entertain. He even manages to find a quotation from T.S. Eliot, of all people, to that effect. In this conviction, however, lie the limitations of his work, no matter how well written or how stylish.

But first, praise where praise is due. The first section of The Pigheaded Soul is devoted to Canadian poets. Guriel’s essay on Anne Carson, a poet who on the surface does not seem cast in his mould, is measured and perceptive. He observes the way in which she rhymes the archaic and the postmodern (a perception I think of her as inheriting from Guy Davenport) and compliments her ability to create startling images. He thinks that her work was strongest at the beginning and has grown more tiresome with each new book, an opinion I happen to share. He quotes a passage (I am not certain which book it is taken from) which he rightly criticizes as cut-up prose, and not very interesting prose at that, but he also notes that from the Vesuvius that is Anne Carson “much of worth has bubbled up.” At the end of his essay he picks and chooses bits and pieces for a Carson book he would call Volcanoes, committing himself admirably about his likes and dislikes in her oeuvre. He is funny in a second Carson review, this one devoted entirely to her book Red Doc, admitting (as reviewers are surely often tempted to, but rarely do) that if he were not reviewing the book, he would have given up on it long before reaching the end. A review of Dennis Lee’s 2007 book Yesno begins with some unnecessary and off-puttingly disrespectful badinage, then boldly goes on to dis a collection that, on the basis of his citations (“How can the/tonguetide of object/sub-/jection not garble what pulses in/isbelly”) unarguably merits it. Don Coles gets Guriel’s deep respect by contrast, and so does a book by Brian Bartlett hewed directly out of some family letters and turned into found poetry, a genre I would not have expected this critic to countenance. (The book in question, Dear Georgie, “is no mere stunt; it’s a great Canadian war poem.”) Part I concludes with two journalistic pieces, on the Griffin Poetry Prize and the so-called Battle of the Bards respectively, and Guriel is in fine fettle here. He is funny without being dismissive, astute, even somewhat self-effacing in a charming way but without giving up his nose for the ridiculous.

Part Two focuses primarily on American poets, with reviews of books by Seamus Heaney and Alice Oswald thrown in, as well as a piece about the musician Alex Chilton and two essays that explore the use of poets (or anthologist-poets) in novels. As I noted earlier, Guriel writes outstandingly about the poetry of Dorothy Parker, a writer who, whatever her many talents, was not much of a poet, really. Guriel recognizes this (so did she, in fact), while still wanting to retain her services for cutting through the crap and pretension of much of what passes for modern poetry. (This is his view, not mine.) If poetry is meant essentially to entertain, of course, Parker is your girl, and she certainly brings out the best in this admirer. Reading him on her, I half expected him to utilize her poems as a test case for the privileging of the dulce over the utile in poetry, but he missed the opportunity, or so it seems to me.

Guriel is excellent on Kay Ryan, although I am a bit mystified at his calling T.S. Eliot a “yuppie” in this essay. (Has the word morphed into something other than young urban professional?) His contention that “Ryan’s poems always seemed to angle for something like the ideal audience of a universal reader” is sensible, although one might counter that such an audience is drawn to her work by its weakest characteristics. A long piece on novels by Nicolson Baker and Roberto Bolaño demonstrates that Guriel is an astute reader of fiction too, although I am puzzled by his insistence, at the conclusion of this essay, on the proposal that “in taking poetry less seriously than, say, a visceral realist, [a poet]might just wind up taking it more seriously.” I’m not sure that this passes the test of logic. Further pieces on e.e. cummings and the Spectra hoax of 1916 seem a bit passé. Guriel’s discovery that cummings, under all the trappings of the avantgardiste, is really just a romantic, and an adolescent one at that, is hardly a revelation. As for the poets who perpetrated the Spectra con, Guriel seems mostly interested in using them as a way to flog the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets and the Flarf gang. (“They are hucksters conning themselves.”) His longer examination of Charles Bernstein’s poetry is far more serious and convincing. He sees Bernstein as less a poet than a Barthesian “scriptor,” someone who “knots together pre-fabricated strands of language, cadged from the culture.” This is perceptive. Guriel’s tsk-tsking Bernstein for seeming to sell out – the once avant-garde poet now has a named chair at a university and publishes with Farrar, Straus and Giroux – seems less warranted. All cutting edge poetry eventually comes to seem arrière- rather than avant-garde, after all, and Bernstein’s path in life doesn’t seem to me especially egregious in this regard.

Jason Guriel’s often-stated belief that poetry should entertain is provocative for certain, and he enjoys the role of provocateur. His glib pronouncements on a bad poet (Jane Mead, for example, is “less poet than stenographer,” a barb almost as good as Mordecai Richler’s deft consignment to hell of Frederick Philip Grove as “a good speller”) are great fun, and make his reviews and essays themselves good entertainment. But most poetry surely aspires to a bigger goal than TV or Hollywood movies or YouTube videos of cats playing the piano, all of which aim at the entertainment factor as their primary target. Despite Guriel’s approbational quoting of August Kleinzahler’s statement that “art’s exclusive function is to entertain, not to improve or nourish or console,” this remains a shallow view of art. Poetry does console, nourish, and teach at times, and is no worse at all for doing so. Who isn’t consoled by “Lament for the Makeris,” nourished by Keats’s odes, improved (or uplifted, or moved) by Canto 47 or the “Ode to Walt Whitman” or Tristia or Briggflatts? Most of these great poems have entertainment value, of a sort, too, but it is not their primary motivation, nor should it be. When Guriel suggests that some of the classic Modernist poets should have “lightened up” a bit at times, okay, one can certainly agree with that. I remember how refreshing it was to read a poem of Robert Lowell’s in which he quoted T.S. Eliot as starting a sentence with “Balls!” Who knew that the dour Eliot could talk like that? It was good to know TSE could be a regular guy as well as a cultural mandarin. But the lack of any entertainment quotient in The Waste Land is obviously irrelevant. I hope that Jason Guriel continues to write his irreverent and entertaining reviews and essays. But if it’s entertainment he’s after as a cultural consumer, maybe he should look to other forms than poetry for his fix.

From CNQ 91: The Nostalgia Issue (Fall/Winter 2014)