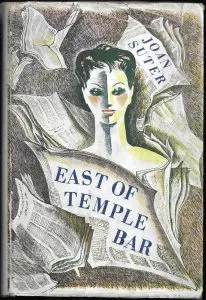

by Joan Suter

London: C & J Temple, 1946

190 pages.

Eighteen-year-old Eve Smith is painting her nails at the London offices of Consolidated Press when in walks Hugh Fenwick. He churns out adventure stories for the company’s boys’ magazines. She’s a sub-editor at one of Consolidated’s romance periodicals, to which Hugh is submitting a tale of love gone wrong.

Two or three years older than young Eve, Hugh resents her at first. Eve got her job—“a sop for boredom”—because she’d gone to school with the daughter of one of the company directors, whereas Hugh had been scrambling for a position in the magazine trade since the age of fourteen. But evening finds them in the local, drinking pints together like best friends. Hugh tells Eve his dreams of being a theatre critic. Eve surprises herself by responding that she aims to be a journalist, when, in fact, she’s never felt an attraction toward writing of any kind.

Eve writes her first story the next day, placing a well-heeled pump on the first rung of the ladder of success. She soon leaves Consolidated for the Morning Chronicle, then the Morning Chronicle for the Sunday Sun. By the time she’s wooed away by the News Record, Eve is so well-known that adverts featuring her photo are affixed to the sides of double-decker buses. Eve’s next move has her leaving the paper trade altogether to become a novelist. Her first endeavour enjoys great praise, numerous printings, and a sale to Hollywood. Hugh also achieves success, largely through Eve’s help, by becoming a critic and editor with Show Pictorial. If there’s disappointment, it is found in their respective love lives. Both flit from one partner to the next as initial excitement turns to boredom. “Funny,” Eve tells Hugh, “but it doesn’t matter how hard I try, I can’t dissemble and I can’t recapture the love I had for them the day before yesterday, although it was so very real at the time. The only way I should ever marry would be if someone came along and did it out of hand…married me within the first few weeks, while that first, fine, careless rapture was on me.” Hugh is about to respond that perhaps they should take a chance on each other, “but the telephone bell rang and he lifted the receiver to hear the voice of his favourite blonde.”

And then, “within the first few weeks,” Eve marries handsome engineer Roger Pelham.

Is this the real life? Is this just fantasy? East of Temple Bar opens in 1930, but the Great Depression does not exist. Careers are on an ever-upward trajectory and the money is more than good. On his honeymoon, Roger’s masculinity is injured when he learns that his bride has the greater income. “But Roger,” says Eve, “surely you know that writers and show people always earn fantastic sums.”

Yes, this is fantasy…but fantasy grounded in real life.

East of Temple Bar is a debut novel. As might be expected, it has autobiographical elements. Author Joan Suter began her writing career at London’s Amalgamated Press, where she edited and wrote for magazines like Children’s Sketch and Woman’s Friend. She left to become a features writer at the Sunday Dispatch and Sunday Pictorial. The August 18, 1938 [London] Daily Herald features a photo of the author posing before a dart board with journalist “Punch” Kerr, whom she wed “[a]fter a romance of 14 days.” The Daily Herald reports that they met in a darts march.

On her honeymoon, Eve dazzles pub patrons with her skill at darts, after which she settles into a marriage bereft of passion. This is the point when real life intrudes in the form of the Second World War. Hugh enlists in the army, Roger serves in the Navy, and the reader is left to speculate as to which will die.

Joan Suter and “Punch” Kerr (journalist Ogilvie MacKenzie Kerr) divorced in 1946, just as East of Temple Bar was being put to bed. Both remarried that same year; Joan to James Walker, formerly of the 12th Canadian Tank Regiment.

The newlyweds settled in Val d’Or, Quebec, which served to inspire Suter’s 1953 memoir, Pardon My Parka. Published under her married name, Joan Walker, it received the Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour. Her next book, Repent at Leisure, a novel about an English war bride in Canada, was the winner of the 1957 All-Canada Award for Fiction. It was followed in 1962 by Marriage of Harlequin, a historical novel revolving around the life of eighteenth-century British dramatist and politician Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Joan Walker (née Suter) lived another thirty-five years, dying in 1997 at the age of eighty-six. She never published another book.

Suter being very much a forgotten writer, I admit my interest in East of Temple Bar has much to do with it being so hidden. The novel was published overseas, under the author’s maiden name, before she immigrated to Canada and married her second husband. Library and Archives Canada does not hold a copy, nor does the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library. I’m happy to have paid more for one with a dust jacket. The text on the front flap concludes:

This is not a book to approve or disapprove [East of Temple Bar was banned in Ireland]. It is the type of fiction which is more revealing than history. To start it is to surrender oneself to the grip of drama; to complete it is to gain an insight into the fastnesses of the realm of life whose boundaries are known to all; but whose heart to few.

I did complete East of Temple Bar, but can’t say that it provided insight into the fastnesses of the realm of life. It did provide insight into Fleet Street and the British publishing world, as it was in the first half of the twentieth century. The novel’s value comes in what it reveals of history, particularly social history: the petty jealousies, the drunken evenings, the one-night stands, the dirty weekends, and of course, the dart matches.

I neither approve nor disapprove.

—From CNQ 111 (Spring/Summer 2022)

We post only a small fraction of our content online. To get access to the best in criticism, reviews, and fiction, subscribe!