Trivial Pursuit almost seems an answer to a trivia question today, but in 1982 it enjoyed a magical Christmas as the North American gift of choice. The following year it repeated the feat. The story behind Trivial Pursuit was so good, and so Canadian, that it was circulated in the media for months on end and even turned into a 1988 feature-length movie: Two struggling journalists, frustrated by missing Scrabble tiles, decide to make a board game of their own and end up multi-millionaires.

Trivial Pursuit almost seems an answer to a trivia question today, but in 1982 it enjoyed a magical Christmas as the North American gift of choice. The following year it repeated the feat. The story behind Trivial Pursuit was so good, and so Canadian, that it was circulated in the media for months on end and even turned into a 1988 feature-length movie: Two struggling journalists, frustrated by missing Scrabble tiles, decide to make a board game of their own and end up multi-millionaires.

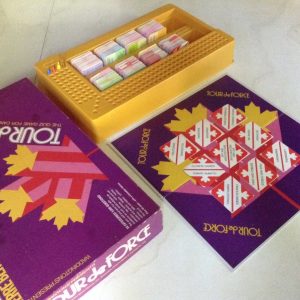

There’s more to it than that of course, but this column is about Tour de Force, a trivia game created by two men who were already quite wealthy. In 1984, the year it landed in Eaton’s and the Bay, Pierre Berton and Charles Templeton were two of the country’s long-standing, bestselling authors. One had made good money from television, the other had made good money from film, and both had enjoyed fourteen years together as co-hosts of the radio program Dialogue.

Tour de Force was a less successful collaboration.

I’m guessing the whole thing was Templeton’s idea; he always fancied himself an inventor. Mattel’s Teddy Warm, a microwavable bear you zapped then popped in your child’s crib, was his. As chief spokesman for Tour de Force, Templeton acknowledged Trivial Pursuitand its lesser rival, Isaac Asimov Presents Super Quiz,as inspirations, while encouraging comparisons through flag waving. “I wanted Canadians to have a truly Canadian quiz game,” he told Gazette journalist Nancy Durnford, “one that was fun to play.”

Both Templeton and Berton were in Montreal for the February 9, 1984 launch. The next week they were back in Toronto for a Tour de Force charity event that pitted everyday folks against local luminaries Ben Wicks, Jack McClelland, June Callwood, and Bob Rae.

Waddington’s Games president Bertie Watson anticipated fifty thousand in sales. Templeton claimed one hundred thousand had shipped.

Watson would be disappointed. Let’s say Templeton was misinformed.

As Christmas 1984 approached, Pierre Berton did his darndest to spur sales with the claim that David Frost would be launching an international version of the game in London.

There was never was an international edition.

Berton went on to feed lazy newspaper columnists stories of intense competition. Tour de Force was being called “Tour Divorce,” he said. One woman had even thrown the game board at her husband!

I can understand her anger. Tour de Force retailed for thirty dollars, and thirty dollars was a lot of money for something so cheap.

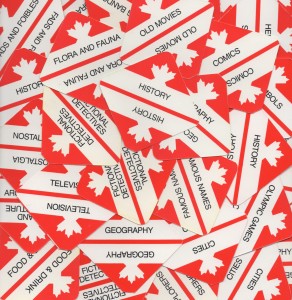

For Waddington’s Games, the most expensive component was surely the question cards. Fourteen hundred, containing five thousand questions; had they not been so poorly produced they would’ve overwhelmed the measly five hundred cards and three thousand questions Trivial Pursuit offered. Most Tour de Force cards feature four questions, two of which are printed upside down for use in some future game. Players must answer the first of the two right-side-up questions, but can take a pass on the second. A varying number of points is awarded for each correct answer; single points deducted for incorrect answers.

Progress is measured by moving pegs on a cribbage-like board composed of the same thin plastic found in supermarket cookie trays. Berton and Templeton were secretive, but I discovered – when I counted the holes – that forty points would win a game.

Excitement comes courtesy of the odd star card, which is worth ten points. Even greater excitement is added by the possibility of achieving a tour de force,which occurs when a player correctly answers the questions posed on five consecutive cards, bringing sudden victory.

What made Trivial Pursuit so popular was that the game had less to do with strategy than knowledge; it was entirely possible for a novice to defeat a veteran player. The same is true of Berton and Templeton’s game.

I played ten rounds against various opponents. The first ended in the sixteenth minute, when I scored a tour de force. The second ended in the twenty-first minute, when one of my opponents matched the feat. Twelve minutes later, I achieved my second tour de force. A third followed in the very next game.

Do not be impressed by this. The questions are remarkably easy. These ten gave me my first victory:

Q: The title of this George Orwell novel is simply a date. (1 pt)

A: 1984

Q: Life in 1984 was lived under the constant scrutiny of

who (or what)? (2 pts)

A: Big Brother

Q: These streets form Hollywood’s most famous intersection. (1 pt)

A: Hollywood and Vine

Q: This theatre imprinted star’s [sic]footprints on its

concrete sidewalk. (2 pts)

A: Grauman’s Chinese Theatre

Q: Name Luke’s two droid friends in The Empire Strikes Back? (2 pts)

A: R2-D2 and C-3PO

Q: What kind of creature was Chewbacca? (3 pts)

A: A Wookee[sic]

Q: In which city is the Saddledome? (2 pts)

A: Calgary

Q: What is the name of the annual rodeo in Calgary? (2 pts)

A: The Calgary Stampede

Q: Who wrote the Canadian classic Anne of Green Gables? (1 pt)

A: Lucy Maud Montgomery

Q: Which province is the setting of Anne of Green Gables? (1 pt)

A: Prince Edward Island

The last four questions are atypical. Despite the thousands of maple leafs in its design, Tour de Force has relatively few Canadian questions. In 1986, two years after the game’s failure, Ontario schoolteacher Ken Fisher revealed that he’d been paid to supply over ninety percent of the five thousand trivia questions.

Q: Who was Ken Fisher?

A: He was the man behind Isaac Asimov Presents Super Quiz.

Q: What was Isaac Asimov’s role in Super Quiz?

A: Nothing.

I’m now beginning to wonder just how much Berton and Templeton had to do with Tour de Force. What either man knew about The Empire Strikes Back is up for debate, but it’s clear that both had mastered the apostrophe.

I won seven of the ten Tour de Force games I played, and so claim title of Tour de Force champion. I do so only because I’m certain that I’ve played more games than anyone else alive.

From CNQ 95, The Games Issue (Spring 2016)