A lecture delivered as the “Immortal Memory” address at DaPoPo Theatre’s “Not Quite Burns Night,” January 24, 2020, in Kjipuktuk/Halifax.

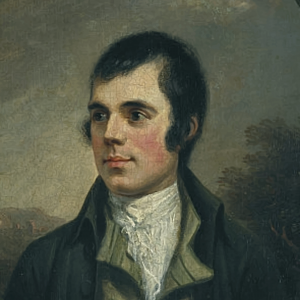

I first encountered Robert Burns not as the Bard of Ayrshire, nor as the People’s Poet, nor (as the wonderful epithet has it) as the “heaven-taught plowman,” but rather—and rather dryly—as exhibit A in the definition of simile which appears in a classic scholar’s primer, M H Abrams’ Glossary of Literary Terms.

I first encountered Robert Burns not as the Bard of Ayrshire, nor as the People’s Poet, nor (as the wonderful epithet has it) as the “heaven-taught plowman,” but rather—and rather dryly—as exhibit A in the definition of simile which appears in a classic scholar’s primer, M H Abrams’ Glossary of Literary Terms.

Now a simile, as every schoolgirl knows, is a comparison asserted using the word “like” or “as.” The classic example that Abrams gives, blithely Englishing Burns’ word luve, is the first line of a song that Burns collected, apparently from “a country girl” (and who knows what else he may have collected from her?) and passed along to the Edinburgh musician Pietro Urbani in 1793: “O my love’s like a red red rose.”

My love’s like a red red rose. A comparison, using the word like: a textbook simile.

If Burns had written “My love is a red red rose,” Abrams informs us, blithely ignoring the country lass, he would have been using the figure of speech called metaphor, a comparison made without the comparison words like or as, but rather with the copular verb to be. Is. My love is a red red rose. If simile is comparison, metaphor is identity.

We will get back to metaphor. For now, let us return to simile.

My love is like a red, red rose.

What does it mean to be “like” something? To resemble it? To take after it?

“Is it not like the king?” says Marcellus to Hamlet, of Hamlet’s father’s ghost.

“As thou art to thyself,” says Hamlet.

“Love thy neighbour as thyself,” we are told in the New Testament—another simile. But—as a priest once pointed out to me—this doesn’t mean very much if we don’t like ourselves, in the first place.

But surely we can be like something, without liking it—without feeling, when we behold it, “our heart overflowing with what is called liking,” to use Burns’ phrase. Surely. God makes man, we are told, in His likeness. But whether He likes man—that is another question.

*

“A red red Rose” is one of the great love songs in the English (perhaps I should say the Scottish) language. But what are the great like songs?

Central in the canon, for me, is Sancho Panza’s beautiful ode to Don Quixote, in the musical Man of La Mancha:

“Why do you follow him?” Aldanza asks the devoted squire of the Don.

Sancho, the squire, wracks his mind: “I follow him because … because … I like him.” And then, singing: I like him, I really like him, pull out my fingernails one by one, I like him.…

Sancho Panza likes Don Quixote—but they are not at all alike. Indeed, one might say they are a picture of unlikeness.

“Unlikeness is us,” says the speaker, in one of the oldest love poems in the English language, an enigmatic lyric called Wulf and Eadwacer. Here it is in Christopher Patton’s new translation:

As if one had made the people an offering.

They will receive him if he comes in violence.

Unlikeness is us.

The wolf is on an island. I am on another.

Mine is secured and surrounded by marsh.

The men on that island are glad at war—

they’ll receive him if he comes in violence.

Unlikeness is us.

I have borne a wolf on thought’s pathways.

Then it was rainy weather and I sat crying.

When the war-swift one took me in arms,

The joy he gave me, it was that much pain.

Wolf—my Wolf—thoughts of you

sicken me. How seldom you come

makes me anxious, not my hunger.

Listen, onlooker, to our miserable whelp

a wolf bears to woods.

Easy to part what was never joined;

our song together.

Unlikeness is us. We do not know who the speaker is, but we know that the speaker is not like their lover. Their lover is a wolf.

The speaker is not like their lover, and the speaker may not even very much like their lover. Wolf—my Wolf—thoughts of you sicken me. How seldom you come makes me anxious, the speaker says.

The speaker is not like wolf; the speaker does not like wolf.

The speaker loves wolf.

What is this love, this passion of unlikeness? What is it like? Well, says Burns’ country lass, it’s like … It’s like a red red rose.

*

In the commonplace book he kept between April of 1783 and October of 1785, Robbie Burns wrote:

I have often thought that no man can be a proper critic of Love composition, except he himself, in one, or more instances, have been a warm votary of this passion. As I have been all along, a miserable dupe to Love, and have been led into a thousand weaknesses and follies by it, for that reason I put the more confidence in my critical skill in distinguishing foppery and conceit, from real passion and nature.

To hear Burns speak, you would think him a hoary Bard of seventy; in fact, at the time he wrote these lines, he was twenty-four. Perhaps this should not surprise us. One knows everything about love when one is young. It is only as one ages that one acquires the rudiments of an ignorance in the discipline.

At twenty-four, Burns had had “major associations,” as his editor delicately calls them, with seven women: Nelly Kilpatrick, Peggy Thomson, Tibbie Steen, Ellison Begbie, Mary Morison, Agnes Fleming, Anne Rankine, and several “Tarbolton Lasses” whom the editor does not deign to count.

Nelly, Peggy, Tibbie, Ellison, Mary, Agnes, Anne: forgotten bards. I wonder if any of them is the anonymous author of “My Luve’s like a red red rose.” We know, for instance, that Agnes liked to sing, and that Burns listened to her singing with “religious devotion.”

“My love,” in what I am now going to start calling Agnes’ poem, refers doubly: it is an epithet for the beloved; it is also the name of the passion that connects the speaker to their bonny lass. The speaker is not like their bonny lass. The speaker may not even like their bonny lass: but the speaker loves her, they will love her, till a’ the seas gang dry:

Till a’ the seas gang dry, my dear,

And the rocks melt wi’ the sun:

I will love thee still, my Dear,

While the sands o’ life shall run.—

To anyone who has been in love, who has been, as Burns says, a warm devotee of the passion, the next line will come as no surprise:

And fare thee well, my only Luve!

We protest the eternal nature of our affections only to turn around and say farewell. That is humanity for you. That is love. Thus Burns moves on from Nelly, to Peggy, to Tibbie, to Ellison, to Mary, to Agnes, to Anne. Wolf leaves for his Island. Unlikeness is us.

And yet. And yet, says the Lover, I will come again.

And fare thee weel, my only Luve!

And fare thee weel, a while!

And I will come again, my Luve,

Tho’ it were ten thousand mile!—

I will come again.

“He will come again,” says the prayer book, “to judge both the quick and the dead.”

“It was but a little,” says the speaker in the Song of Songs, “till I found him whom my soul loveth.” I will come again, my Luve, / Tho’ it were ten thousand mile.

*

When I teach simile to my students, in my introductory course on literature at Saint Mary’s University, I tell them that in any simile we have the tenor (“my Luve”), the thing being described—and the vehicle (“a red red Rose”), the thing by means of which the tenor is being described.

The vehicle and the tenor are connected by often unspecified grounds: those aspects or properties the vehicle and the tenor might be said to share. How is my Luve like a red red Rose? What are the grounds for the comparison?

Well, my Luve is like a red red rose because my Luve is beautiful, I might say; or because my Luve is thorny; or because my Luve is endlessly unfolding; or because my Luve is mortal. There is, of course, no one right answer. Poetry is a both/and world.

It beguiles me, to think about the grounds for the comparison that Agnes puts so pithily: my Luve’s like a red red rose. But I have always thought, about this simile, that the grounds for the comparison is actually less important than the fact that the speaker compares and then compares again—and then compares again:

O my Luve’s like a red, red rose,

That’s newly sprung in June;

O my Luve’s like the melodie

That’s sweetly playe’d in tune.

No sooner does the speaker come up with one comparison, they discard it in favour of another. And another. For my Luve is like … everything. It is (or he is or she is or they are) like the keys that are sitting on my desk as I type these words; it is like a man’s scarf, like a woman’s hairdo; it is like the wind; it is like the sky. My Luve is that which beggars comparison. It is … unlikeness.

And yet, we are told, it creates us in its likeness. My Luve is like … us.

*

My Luve is like us—and then, with one great sweep of its hand, the way a professor might erase the word “like” from the bard’s comparison, trading simile for metaphor, it is us. It becomes us. The Word becomes flesh and dwells among us, full of grace and truth.

(It is perhaps for this reason that Burns, educated as he was by those great forgotten Christian bards, Nelly, and Peggy, and Tibbie, and Ellison, and Mary, and Agnes, and Anne, “never considered his sexual expertise to be at loggerheads with personal religious morality.” As the editor reminds us, in the text of his commonplace book, Burns commends to his reader the practice of “keeping up a regular, warm intercourse with the Deity.”)

*

It is hard not to think of Burns as Wulf to Agnes’ Eadwacer: as the man who goes, relative to the woman who stays. The abandoned-woman song is a well-established genre, in part because traditionally men have had freedom of movement. They’ve been able to go away; the women have had to stay behind, raising the whelps and the bairns. But women, too, abandon their loves: abandon their parents to cleave to their husbands, abandon their husbands to cleave to their children, abandon their children to cleave to their lovers, abandon their lovers to cleave to their vocations, abandon their vocations—well, to die. In death, too, we abandon our loves, even as we assure them “I will come again.”

I like to imagine Agnes Fleming singing this song to Robbie Burns: a lass, stepping into the role of a lass’s lover, to sing to a lass’s lover this song of his love—which is also her love for the duration of the song. I am like you, her singing seems to say. I am you.

O my Luve’s like a red, red rose,

That’s newly sprung in June;

O my Luve’s like the melodie

That’s sweetly play’d in tune.—

As fair art thou, my bonie lass,

So deep in luve am I;

And I will love thee still, my Dear,

Till a’ the seas gang dry.—

Till a’ the seas gang dry, my Dear,

And the rocks melt wi’ the sun:

I will love thee still, my Dear,

While the sands o’ life shall run.—

And fare thee weel, my only Luve!

And fare thee weel, a while!

And I will come again, my Luve,

Tho’ it were ten thousand mile!—

—From CNQ 110 (Fall 2021/Winter 2022)

Luke Hathaway has been before now at some time boy and girl, bush, bird, and a mute fish in the sea.

We post only a small fraction of our content online. To get access to the best in criticism, reviews, and fiction, subscribe!