Jack London’s epistolary relationship with Canadian socialist agitator Wilfrid Gribble

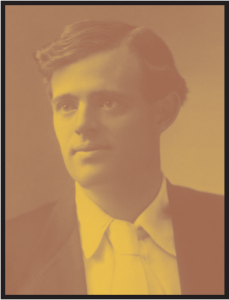

At least one of Jack London’s Canadian connections is well-known. In the summer of 1897, he went to the Klondike for the Gold Rush. Twelve months later he returned to California, with no riches to show for the experience and a case of scurvy to boot. But he had more than enough material to make his reputation as an author of adventure stories. After the publication of The Call of the Wild (1903), London was acclaimed as the American Kipling. He went on to become one of the most popular writers of his time. In Dawson City today, there is a small Jack London Museum.

London came out of the lower depths of the American working class of the late nineteenth century. He started as a newsboy, did odd jobs on the waterfront, raided oyster beds, worked in a cannery, and went to sea on a sealing ship. The year he turned eighteen, in 1894, he crossed the continent as a hobo, one of a straggling army of underemployed men who were trying to attract the attention of the American federal government.

That odyssey, he later wrote, taught him that he was no more than a work-beast at the bottom of the labour market. In New York State, he spent a month in jail—“a living hell, that prison”—where he saw guards throw a man down six flights of stairs. London made his way home to the West Coast by hopping freights on the Canadian Pacific Railway. He was detained by police in Winnipeg, but talked his way out with some tall tales that already showed his talent as a storyteller.

Back in California, London decided to return to school and even, briefly, attended university classes. At the public library in Oakland, he came under the influence of a Queen’s University graduate by the name of Frederick Irons Bamford. This well-read librarian introduced him to Darwin and Marx, a potent mix that convinced London, like others of his generation, that the logic of social evolution led to socialism. He soon joined the Socialist Labor Party and was a member of the Socialist Party of America until shortly before his death in 1916.

Given London’s enormous reputation for writing animal and adventure stories, it is sometimes surprising to learn that he was a radical social critic. His People of the Abyss (1903) is a first-hand exposé of urban social conditions, and The Sea-Wolf (1904) is a gripping story that highlights exploitation and manipulation on board a sealing vessel. London’s most political novel, The Iron Heel (1908), is a dystopian epic, set only a few years forward in time, about the suppression of labour and socialist movements by the prevailing capitalist oligarchy.

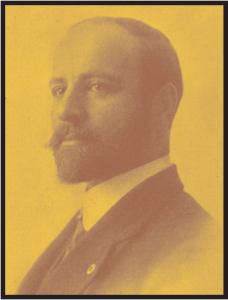

In the spring of 1913, an itinerant Canadian by the name of Wilfrid Gribble arrived to visit London at his ranch in the Sonoma Valley. He was attracted by their shared political affinities and London’s standing invitation. “Our latchstring is always out,” London would write to correspondents, and a steady stream of visitors came to the door, including fellow writer Upton Sinclair and the veteran anarchist Emma Goldman. By the time he arrived there in April 1913, Gribble was known in Canada as a socialist agitator and occasional poet. Born in Devon, England, in 1872, he served in the Royal Navy as a young man before following his mother and father to Ontario in 1900. He worked as a carpenter in Toronto, where he also joined the Socialist Party of Canada. Likely drawing on the example of his clergyman father, Gribble earned a reputation as a writer and speaker who, said one listener, “throws all his powers into his assertions, and drives home every statement in a remarkable manner.”

Gribble typically delivered hard-hitting messages that aimed to educate his listeners about the underlying evils of the social order. As he told an open-air crowd in Regina in 1913, “There is not a person in the world today who is practicing the Golden Rule, nor is there one who is able to practice it. It is not possible under capitalism.” By this time, Gribble had also published his own “neat little volume of virile verse” under the title Rhymes of Revolt. In one of his recurring themes, he linked modern socialism to age-old battles against autocracy and slavery: “Those old time rebels knew right well, They did the best they knew, They went their way ’ere Freedom’s day, And left us a work to do.”

Information about Gribble’s visit with Jack London may be gleaned from several surviving letters that passed between them. Like other socialists, they addressed each other as “Comrade” and signed themselves “Yours for the Revolution” and “Yours in Revolt.” Men of about the same age, they were clearly on good terms. London signed one of the letters “Affectionately yours.”

On his way back to Vancouver after his week-long visit, Gribble wrote to thank London and his wife Charmian for their “generous and comradely hospitality.” He also included an apology for the effects of “too much John Barleycorn” on his last evening with them. London—who had just finished writing his “alcoholic memoirs,” published that year as John Barleycorn—was reassuring: “Everything is all right with me so far as you are concerned, and Mrs. London says everything is all right. Therefore everything must be all right. Now, do you please forget anything that might be bothering you in any way.”

In the same letter, Gribble tried to express his admiration for London in measured terms: “I feel towards you exactly as I feel towards every other rebel who I know to be true, earnest and single-minded in the cause of the workers, except on the score of your ability, and in that you are to me ‘the noblest Roman of us all.’” He also told London that some of the latter’s economic discussions were “in my opinion, rather faulty” and that there were plenty of good economists who had done better work. London’s real achievement, especially in his pamphlets, was to awaken the intelligence of the working classes and cultivate a rebel spirit: “you have done more to forward the revolutionary movement than any other writer that America has produced.”

Was Gribble worried that London’s radical commitment might be faltering? As a property owner, London had taken great pride in showing Gribble his prize stallion and was greatly preoccupied with managing the ranch and building a new residence, to be known as Wolf House. Perhaps this is why Gribble’s letter ended on a note of caution. “I rejoice in your success, and realize that you will have greater yet,” he wrote, but he also exhorted London to “stay with us” and “remain in our fight, what you aptly term ‘the big fight’, till it is won.”

As was his habit with visitors, London presented Gribble with copies of his books, including the semi-autobiographical Martin Eden (1909), which he read straight through as soon as he reached San Francisco. London also gave him a copy of The Iron Heel, which Gribble had already read more than once. Indeed, Gribble asked London for permission to serialize the novel in the Western Clarion, the Socialist Party newspaper published in Vancouver. It was just what the paper needed, he wrote in thanking London for the gift of serial rights. One of their problems, Gribble said, was that the Clarion declined to publish “soft and sweet sentimentalism or silly abuse of the capitalists” and this made it difficult to attract readers. “To make it popular without stultification,” Gribble wrote, “the Iron Heel just fills the bill.”

Some of the chapters in this futurist novel must have struck contemporary readers as highly optimistic. To stop a world war, there were successful general strikes in both Europe and North America. And in elections, there were landslide victories for the socialists in many countries, including the United States. But the novel also depicted a rising tide of repression that was followed by three centuries of darkness. Since London’s time, critics have come to see The Iron Heel as a forecast of fascism.

Introducing the book in the Clarion, Gribble explained that The Iron Heel had received a mixed response from socialist leaders in the United States. Some had told London that his book was putting the socialist movement back five years, but the author did not agree: “‘To tell the truth’, he told me, with a twinkle, ‘I believe I put it ahead five minutes.’” London later wrote Gribble that the political situation was not improving: “It seems to me THE IRON HEEL is coming truer every day, and day by day.” By this time, London saw himself as a maverick within the Socialist Party. When he resigned, in March 1916, he wrote that it was “because of its lack of fire and fight, and its loss of emphasis on the class struggle.”

Back in Canada, Gribble wrote to London again in March 1914 from “the frigid Canadian backwoods” of his father’s farm near Parry Sound, where he was “’picking icicles out of my mustache and beard.” He recalled his week at Glen Ellen a year earlier as “a purple passage” in his life. He touched on a dozen topics, ranging from his own health and fitness (“there is some difference between the fellow who is writing you now and the wreck who visited you”) to his literary ambitions (“I use rhyme and metre as an aid to make my meaning stick, and latterly, to get a few dollars”). He hoped London would not mind him making liberal use of his books in a coming lecture tour. And, on the principle that “a mouse once helped a lion,” he drew London’s attention to the bitter two-year labour war then underway on Vancouver Island. The coal miners there, he said, “took things in their own hands à la Paris Commune.” Gribble suggested London “could certainly make a red-blooded yarn on the Western Canada miners,” but there is no evidence London took up the idea.

For his part, London reported on his own unhappy year: Wolf House had burned down before construction was finished, and he was plagued with health issues. (He told Gribble he had had appendicitis, but did not mention that his doctor had informed him his kidneys were also badly diseased). There were lawsuits, especially regarding movie rights (“every time I got $20 in sight, four men rose up to try to take it from me by perfectly legal means”). But London reassured Gribble about his speaking tour (“use me in your lectures any way you see fit”) and encouraged him to visit again. Moreover, as Gribble had sent him some of his own verses, London gave him a brotherly seal of approval: “Enjoyed your poems immensely.”

While London continued to bring out two books a year and spent a good deal of time in Hawaii, Gribble had settled in Saint John, New Brunswick. There he counted himself part of a small group of local socialists. In 1915, he married a widow, the former Mary Eliza Currey, who was active in the local suffrage movement. Despite her earlier years as the wife of a conservative local barrister, Gribble declared her to be “a very thoro’ RED” who was well-versed in socialist thinking.

Gribble’s last known letter to London was sent from the city jail in Saint John in January 1916: “Just a few lines to let you know I have fallen into the hands of the enemy. I am ‘remanded for sentence’ after being found guilty of ‘seditious words.’” His wife was standing by, “waiting to smuggle this out.” Gribble had been arrested for making an anti-war speech at a socialist meeting, where he stated words to the effect that “Your King and country will bleed you.” He expected a heavy “penalty,” but escaped with a stiff lecture and a sentence of two months.

After his release, Gribble and his wife left for the United States. They stopped for a time in Detroit, where he was named organizer of the small breakaway Socialist Party of the United States. He likely had plans to visit London, who had sent his congratulations on the formation of the new party that summer. It is not clear if Gribble was aware that London, at first skeptical of the war, had come to see himself as a supporter of the allies in a showdown between civilization and barbarism.

In November 1916, Gribble received news of London’s death, apparently from kidney failure. Writing to Mrs London, he sent condolences on behalf of himself and his wife, and added, “There is no need of a monument to keep your husband’s memory green, for in the work he did and the affection he inspired, he will live for all time . . . ” This has turned out to be true enough, as more than a century later most of London’s books remain in print.

Gribble is lesser known by far, almost invisible to history. By the early 1920s, he had returned to England, where he found a niche working for a network of labour colleges. Under a pseudonym, he published a second book of verse, The Rubaiyat of a Rebel. He also continued to write to Charmian London in California and occasionally gave lectures on “Jack London and His Works.”

—From CNQ 109 (Spring/Summer 2021)

David Frank is a professor emeritus in Canadian history at the University of New Brunswick. His books include J B McLachlan: A Biography and Provincial Solidarities: A History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour.

We post only a small fraction of our content online. To get access to the best in criticism, reviews, and fiction, subscribe!