In his essay, “Steps Towards a Small Theory of the Visible,” John Berger writes, “The impulse to paint comes neither from observation nor from the soul (which is probably blind) but from an encounter: the encounter between painter and model – even if the model is a mountain or a shelf of empty medicine bottles.” This analogy applies also to literary work, but the encounter is between the writer’s imagination and language. Berger continues that the painter must “get close enough for a collaboration to start” and “To go in close means forgetting convention, reputation, reasoning, hierarchies and self. It also means risking incoherence, even madness. For it can happen that one gets too close and then the collaboration breaks down.”

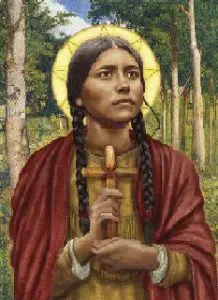

Berger’s assertions provide us with a precise diagnosis as to why, fifty years later, Leonard Cohen’s second novel, Beautiful Losers, remains a failed, fossilized encounter. The novel, according to the book jacket, attempts to relate the “hapless members of a love triangle, united by their sexual obsessions and their fascination with Catherine Tekakwitha, a mythic seventeenth-century Mohawk saint.” What it more accurately surrenders unto is a broken collaboration where Cohen hits manic incoherence and little else. But these symptoms, also, or perhaps, only, offer us a convincing entry point to contemplate why the hardest part of any artistic “encounter” is endurance. On the writing side, most writers can testify to the need for endurance because, unless they’re owed money, no one will notice if they never write another book. Yet on the reading side it can be equally challenging and take another variety of endurance. Do we carry on reading a novel even though it’s an abysmal and torturous experience? How ought this novel to be read? Am I making sufficient effort to read this book on its terms? This can swiftly haemorrhage towards increasingly dour and uncharitable thoughts like: Should the writer have carried on writing this book? How can we encourage writers to stop writing these terrible books while they are in the midst of writing them so we might be spared them? Or is there always something salvageable? Who makes the choice? Do novels ever hit an expiration point? Why do some have built-in obsolescence (forgotten after six weeks and a consoling piece of cherry pie), while others are entitled to endure with far less merit, flagged as postmodern with a folk-singing legacy attached? You might sing in tune off the page, but this doesn’t automatically guarantee harmonics on it.

We could merrily remix Berger’s title for this rhetorical tango to “Steps Towards a Small Theory of Why the Reader Should Stay or What the Hell Possessed the Writer to Remain at this Font. Or, at this frantic hour, for this writer typing this lament to you, How on earth can I write about a novel, which I have agreed to do, when the prose makes me feel dizzy and unwell?”

Simone Weil would contend that I embrace detachment, “necessity and obedience” or that “Grace alone can do it.” I’m forty-five and well beyond graceful or obedient. Necessity lies solely in feeding the detached teenager (mine). On detachment she versed that “Affliction in itself is not enough for the attainment of total detachment. Unconsoled affliction is necessary. There must be no consolation – no apparent consolation. Ineffable consolation then comes down.”

Weil is correct. I have reached unconsoled affliction. There has been no consolation apparent or otherwise in reading Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers. The first one hundred and thirty-four pages of it alone ruined three days of my life. Inexplicably though, ineffable consolation has not come down. Perhaps it is on the way, but it’s now been three weeks and three time zones. I was reduced to reading it while walking around the park in an attempt to crawl my way through its operatic stigmata of grains-of-rice-inserted-into-the-belly-button… what? Threesomes, indefatigable Catholic angst, and earnest mashing of his paintbrush all over a Mohawk Saint (I actually prayed privately that no indigenous woman would ever have to suffer reading this novel).

Weil is correct. I have reached unconsoled affliction. There has been no consolation apparent or otherwise in reading Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers. The first one hundred and thirty-four pages of it alone ruined three days of my life. Inexplicably though, ineffable consolation has not come down. Perhaps it is on the way, but it’s now been three weeks and three time zones. I was reduced to reading it while walking around the park in an attempt to crawl my way through its operatic stigmata of grains-of-rice-inserted-into-the-belly-button… what? Threesomes, indefatigable Catholic angst, and earnest mashing of his paintbrush all over a Mohawk Saint (I actually prayed privately that no indigenous woman would ever have to suffer reading this novel).

Cohen has provided some insight as to why his book is such a pain in the hole. He is on the public record as admitting he wrote it off his face, high on amphetamines, deliberately famished, while living for a time on a Greek Island. What’s missing therefore is a series of lickable page corners to provide a micro dose of LSD every twelve pages to enhance this bad trip. Amphetamines are insufficient. I tried them while reading it. They merely resulted in a massive headache. Though it was a marginally reduced headache compared to reading the book chemically unassisted. The only additional benefit of the Ritalin was that it allowed me to fly around the living room with my hoover to disperse the chronic desire to lie under a concrete block, which reading Leonard, drug-free, results in.

Rather than prattle on here, chemically unassisted, for two thousand words about all that is, to quote my reading notes, the “pointless hell” that is this novel; instead I’ll settle on submitting a few random examples of the prose for your immediate digestion.

“Do I have any right to come after you with my dusty mind full of the junk of maybe five thousand books? I hardly even get out to the country very often. Could you teach me about leaves? Do you know anything about narcotic mushrooms?”

“F. said: Connect nothing. He screamed that remark at me while overlooking my wet cock about twenty years ago. I don’t know what he saw in my swooning eyes, maybe some glimmering of a fake universal comprehension. Sometimes after I have come or just before I fall asleep, my mind seems to go out on a path the width of a thread and of endless length…”

“Her mouth sailed crazily over my body like a flock of Bikini birds, their migratory instincts destroyed by radiation.”

“You thought a heavy shell necklace would draw blood. To kiss her there was to intrude into something private and skeletal, like a turtle’s shoulder.”

“Her freakish nipples make me want to tear up my desk when I remember them, which I do at this very instant, miserable paper memory while my cock soars hopelessly into her mangled coffin, and my arms wave my duties away, even you, Catherine Tekakwitha, whom I court with this confession.”

It continues with this type of rubbishy gibbering for two hundred and fifty-five pages divided into three books. There’s one strong page. It’s page sixty-six. Read that and close it. This is a classic art-school novel, where (Berger’s instructed) encounter occurs between the lobbing of sixty eggs and a wall and uniquely, in the history of the necessary indulgence that is art-school abandonment, nothing stuck to the wall, except page sixty-six. Maybe if you were stoned in a ditch in Grand Prairie in 1966, this novel was a revelation and Lord knows, perhaps it still is a revelation if you’ve had your head inside your armpit for eighty years.

The novel’s reception on publication swung between hyperbolic dismissal – (“The most revolting book ever written in Canada” – critic Robert Fulford) and loopy decanting on its excellence (“Leaves one gasping for breath as well as suitable words” – the Dallas Times Herald). Like the novel itself, neither perspective makes much sense. There’s nothing revolting about this novel, it is just plain daft. The only gasping for breath would result from bolting away from it, while shouting the very suitable words rubbish, rubbish, rubbish, Câlice de crisse de tabarnak.

Committed to understand what I lacked as a reader, I surveyed a few local poets who were upright at the time of its publication. They either remembered very little of it, had no desire to, and/or were in a hurry to go camping. One admitted to being stoned reading it and never having read anything like it. Fair enough. My final attempt to unravel my possible ineptitude for this task resulted in a most unpleasant disagreement on an entirely unrelated topic. Be very careful challenging opinion on Leonard Cohen, it’s like bringing up someone’s ex-partner with a mistaken warm smile on your face.

Is there a desire to protect or pardon literary Cohen because he’s a national sonic treasure, whose music even I enjoy. He certainly looks very dashing in his fedora while singing about oranges and tea and Suzanne and Marianne? Can a socio- or sacro-cartographic argument be made for this novel being “of its time,” where it’s auto-afforded a spot in the museum like a literary artefact, or more accurately, a literary wreck? I’m sure there are some who’ll herald such a trumpet, but not this reader. Blank literary nationalism, geography, and 1966 are a weak basis for maintaining meritless work. Who cares if it was Canada’s first introduction to postmodernism, let’s skip ten years and harp on instead about our second introduction. The “we’d never read anything like it before” argument rather collapses – then, as now – against the history of modernism and more recent experimental work (Eileen Myles, Ann Quin, Jordan Abel, Tamara Faith Berger, Bridget Brophy, Elfriede Jelinek, etc.) that successfully tackles sex, excessive Catholic everything, and the other themes of his unfathomable ramble. Carte blanche cartographic loyalty cannot erase sentences such as:

“Connect nothing: F. Shouted. Place things side by side on your arborite table, if you must, but connect nothing! Come back, F shouted, pulling my limp cock like a bell rope, shaking it like a dinner bell in the hands of a grand hostess who wants the next course served.”

Cohen’s invoked cock has morphed into his literary garden hose by the end of this sentence. God help the poor imagined woman who has to chug on it. All grand hostesses would take early retirement if their rope turned into conjoined penile tissue by the time the pea soup’s ready to serve. Cohen never seems to get over the glans for the entirety of this novel. It’s like he’s forcing oral on the reader, jabbing these God-awful sentences into any innocent auditory orifice.

What’s worth examining, more than the novel, is the lexical agony of having such a book thrust upon you. Or, as the Leonard himself so conveniently supplies, “O God, help me get through this. I am corrupt in stomach. I am cold and ignorant. I am sick in window…”

Wherein lies the point of termination with an unbearable book? There’s an obvious reason to brave it if you are being paid to write about it or if, having bought it, the reader might wish to ascertain how much worse (or better?) the text will become and whether it can sustain this level of awful right to the end. I find there’s an overwhelming physiological condition that descends on me in these circumstances. Medically, it falls somewhere between distressing injury to the vestibular system and the flu. The generic humph of it’s all subjective proves unconvincing since there’s nothing subjective about an overloaded, burdened sentence. It will follow you from 1966. It indicts itself. We are all perfectly capable of them and a novel can bear a few such sentences without graze, but not two hundred plus pages of them.

At one time I would have argued that one should Always Read the Work. I continue to. I’d have argued always read the entire work. Beautiful Losers has persuaded me otherwise. Sometimes there is nothing to be gained from carrying on and there are much better ways to waste time. Namely, one can read something else. Much else. Everything else. Swipe left.

In many ways Cohen did follow what Berger succinctly suggests. He certainly went in close. He went in so close he offers us literary cataracts. He did forget convention. He didn’t give a toss about reputation. Though he was appropriately pissed off at not being properly paid. Respect. He threw reasoning way off to the hillcocks. The two things he failed to discard, and which ultimately scuppered his novel, were hierarchies and himself. He’s alleged to have declared, upon finishing, that he’d written the Bhagavad Gita of 1965 and figured out how to write a novel in three weeks. Both assertions indicate he was raving, as we’d all be raving if we ate nothing and downed speed in a hot spot for ten days. Jesus did forty days and forty nights, but there’s a very good reason he did not bring a typewriter. Could the distance between sense and nonsense fifty years ago have been a daily boiled egg?

—From CNQ 97, the Fall Issue, September 2016