One condition of the present is that it makes it difficult to contend with the past. Looking backwards, one witnesses a teleological collapse; what was and what is are never knotted together quite so tightly as we’d like to believe, and despite our faith in progress, it’s seldom the case that one thing leads precisely to another.

Margaret Atwood released two books in 1972, Survival – an adaptation of her graduate work on the primary themes of Canadian literature’s first century – and Surfacing, a novel about, well, political, personal, and physical survival. Survival remains a touchstone in Canadian literary theory, the first comprehensive study of how writing from Canada expresses who we are on the page. Her basic premise is that our literature is built, as Susannah Moodie had it, from the bush. As a broad, largely uninhabited mass of land, Canada is an ideal backdrop for an ongoing dramatic conflict where humanity is pitted against nature. You might remember from grade-school English that this is one of three basic conflicts from which one might conceivably build a plot.

Today, Survival feels inordinately dated; there’s a half-built syllabus of (by now, often forgotten) texts in every chapter and a pernicious colonial presumptiveness about who has been living on this land and telling stories about it. The pertinent chapter, “First People,” begins with a hedged bet – “Until very recently, Indians and Eskimos [sic]made their only appearances in Canadian literature in books written by white writers.” The chapter goes on to discuss instances of Aboriginal people being collapsed into metaphors for white ideas and experiences. While Atwood nods toward a self-awareness regarding the First Nations here, she commits exactly the same act of collapse by failing, through lack of empathy or imagination, to presume anything but a white readership for her own work. Survival relies on a systematic accounting of the myriad ways in which Canadian literature is built on a faultline of victimization. But in making this point by way of a discussion of how Aboriginal people are depicted in poems, novels, and stories, Atwood misses an opportunity to reflect on the way that her own discussion of the trope normalizes the racism and colonialism she describes.

Designed, in part, as a teaching tool for high school and university English classes complete with thematic reading lists and a near-exhaustive bibliography of both critical and primary texts, the book occasions just a few brief fits of verve and insight in the wry prose that has come to characterize so much of Atwood’s writing (“Canadian authors spend a disproportionate amount of time making sure that their heroes die or fail.”). But on the whole Survival makes for dry, dated reading.

Surfacing, on the other hand, feels fresh and bright over three decades later. Atwood’s second novel simultaneously fits her thesis on the particular, bushwhacked quality of Canadian literature, and gives evidence of her creative resistance to the constraints of a still-forming national genre. The novel sees its unnamed protagonist returning from her boho life in Toronto to the remote, Northern Quebec village of her birth. The visit is occasioned by an unhappy circumstance: the narrator has been summoned by a neighbour because her father has gone missing from his lakeside cabin. She brings three friends with her, urbane and politicized young people with ties to a pseudo-radical community of artists. David and Anna, a couple of feminists who married young, and Joe, the man the narrator is dating but does not love. The plucky, white, and suitably fucked-up foursome spend the week communing with and being challenged by the rural landscape while discussing the concerns of the day: American politics, women’s liberation, and the ways young heterosexual people enjoy having and seeking sex. (That groups of young, educated, liberal white people can be found discussing these exact talking points all over the country today is a matter, I think, of national plus ça change.) Atwood’s protagonist, a young woman nearing thirty, recalls reading guidebooks for surviving in the country’s backwaters as a child, but nonetheless finds herself ill-equipped to navigate the wilderness of contemporary adult life.

Surfacing, on the other hand, feels fresh and bright over three decades later. Atwood’s second novel simultaneously fits her thesis on the particular, bushwhacked quality of Canadian literature, and gives evidence of her creative resistance to the constraints of a still-forming national genre. The novel sees its unnamed protagonist returning from her boho life in Toronto to the remote, Northern Quebec village of her birth. The visit is occasioned by an unhappy circumstance: the narrator has been summoned by a neighbour because her father has gone missing from his lakeside cabin. She brings three friends with her, urbane and politicized young people with ties to a pseudo-radical community of artists. David and Anna, a couple of feminists who married young, and Joe, the man the narrator is dating but does not love. The plucky, white, and suitably fucked-up foursome spend the week communing with and being challenged by the rural landscape while discussing the concerns of the day: American politics, women’s liberation, and the ways young heterosexual people enjoy having and seeking sex. (That groups of young, educated, liberal white people can be found discussing these exact talking points all over the country today is a matter, I think, of national plus ça change.) Atwood’s protagonist, a young woman nearing thirty, recalls reading guidebooks for surviving in the country’s backwaters as a child, but nonetheless finds herself ill-equipped to navigate the wilderness of contemporary adult life.

Toying with the reader’s trust, the narrator initially presents herself to us as she does to her parents and her friends, as a recently divorced woman undergoing what thirty years later would be called a quarter-life crisis. After moving to the city, falling in love, having a child, and developing a career as a commercial illustrator, she finds herself without the future that society would seem to have promised her. Her life appears oriented toward a conventional enough future, rearing her child with her husband, gradually gaining renown for her illustrative work, but there is – for both the narrator and the reader – a shadowy question mark hanging in place of a clear path.

Slowly, the picture comes into focus and we are given to understand that the situation is murkier, more complicated than what our narrator has initially presented, a narrative that is in fact a sort of lie.

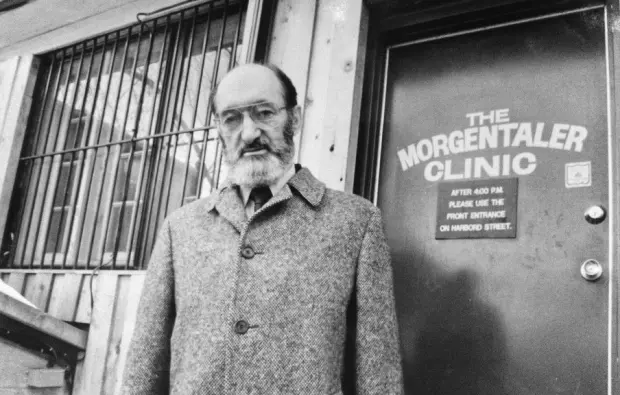

Three years before the publication of Surfacing, Montreal-based Dr. Henry Morgentaler opened the first private abortion clinic in Canada. Canada’s first Criminal Code, ratified in 1892, prohibited all forms of abortion, and it wasn’t until 1967 that the clause was challenged. The first Trudeau government formed a committee, and invited Morgentaler to speak. At the time, a woman seeking a legal abortion would only be allowed to undergo the procedure if she could demonstrate that the pregnancy put her life at risk and/or was the result of incest or rape. She would have to argue her case for an abortion, a procedure that was only legally available in hospitals, before a committee of three doctors, who would then collectively determine the fate of her body. Because so few hospitals provided the service, and general practitioners weren’t permitted to perform it on their patients, many women were unable to access a legal abortion, compelling some to attempt dangerous and unregulated procedures. In 1969, defying existing law, Morgentaler closed his general practice in order to open the first Canadian abortion clinic, where women could safely terminate their pregnancies without suffering humiliation. His clinic was raided by police the following year, and Morgentaler was charged with performing illegal abortions. He would be embroiled in court battles to perform legal, safe abortions for the next twenty years.

That Atwood was able to write a female character with complex feelings about having had an abortion in this context strikes me as exceptionally brave. It’s a difficult task to execute with grace, and one she handles without making the subject matter into an argument – this is not a didactic work, and the prose, at times poetic and others plain, never presents the narrator’s experience as case material for advancing a political side. It’s an altogether astounding achievement, and all the more remarkable when considering the text’s immediate socio-political context.

As with her first novel, The Edible Woman, Surfacing is a blatantly feminist text, interrogating the ways in which both in-stitutional and intimate misogyny affects the development of the self. Gradually, our narrator reveals that she has misled her friends and family, and possibly herself, about her life; she is not a divorcee, but rather the former mistress of a married man. She did not have a child; she had an abortion.

In addition to pioneering abortion access, Morgentaler was at the forefront of technological developments that increased the procedure’s safety. He was the first physician in North America to perform abortions using vacuum aspiration, a much less invasive procedure than sharp curettage, the technique used by hospital physicians at the time.

Sharp curettage, a blind procedure performed without an ultrasound or incision, required the patient to be sedated on ac-count of the extreme pain caused by both the forced dilation of the cervix so that the contents of her uterus could be scraped out, and by the scraping itself. Atwood’s narrator offers a graphic and personal account of the procedure:

…they shut you into the hospital, they shave the hair off you and tie your hands down and they don’t let you see, they don’t want you to understand, they want you to believe it’s their power, not yours. They stick needles into you so you won’t hear anything, you might as well be a dead pig, your legs up in a metal frame, they bend you over, technicians, mechanics, butchers, students clumsy or sniggering practising on your body, they take the baby out with a fork like a pickle out of a pickle jar.

The dead animal is a recurring motif throughout Surfacing – our narrator winces as she pierces a frog to use as fishing bait, and a pivotal moment in the journey occurs when the group happens upon a great heron, murdered and hung up in a tree. Even before that, one of the narrator’s terrible friends, a sessional professor, introduces the theme:

“’Do you realize,’ David says, “that this country is founded on the bodies of dead animals? Dead fish, dead seals, and historically dead beavers, the beaver is to this country what the black man is to the United States. Not only that, in New York it’s now a dirty word, beaver. I think that’s very significant.’ He sits up and glares at me through the semi-darkness.’

‘We aren’t your students,’ Anna says, ‘lie down.’”

(A note on that explosive, racist clause: David and Anna are characters deployed precisely to prove how repulsive humanity is outside of nature. The casual racism of David’s remark here is typical of the character, and is, in my reading, one of many instances where Atwood craftily indicts the exact kind of people who most need indicting – the beneficiaries of systemic oppression who feel that merely acknowledging the existence of oppression exculpates them from their own complicity in the system from which they benefit. David and Anna are a distorted foil constantly magnifying the ills of civilization, the posturing and politics and psychology.)

Dead animals are a constant in these pages, as symbols and fact. Grief over her aborted fetus blossoms into mania when the protagonist finally confronts her father’s death. She separates from herself and her friends in the wild rural environment of her home after watching them bring their politics, their art, into an intimate, even bestial sphere. Encountering her father’s body, which death has rendered mere animal flesh, has the uncanny effect of breaking the narrator’s mind open; in her pain and her anger, she rejects the burden of narrative, of social order and constraint, and liberates herself, becoming wild, animalistic.

After destroying the evidence of her domesticity – the plates, the bedding, the paperwork, the family keepsakes and knick-knacks – she heads out toward the lake, craving separation from all the agonies borne from the human condition: “When nothing is left intact and the fire is smouldering I leave, carrying one of the wounded blankets with me, I will need it until the fur grows.”

The narrator’s descent into animal madness is far from sudden, even if it hinges on a specific moment, one where she seems to decide definitively to abandon humanity. In fact, looking more closely one sees that there was no precise moment when our narrator became an animal, became nature – the genius of Surfacing is in Atwood’s ability to demonstrate how facile the idea of humanity vs. nature is. Whatever the environment, we can’t escape being mere animals, destined to fuck up and die, even as we persuade ourselves we spend our lives making choices that would suggest otherwise.

Reading Surfacing in 2016, I was struck by the courage it would take, even today, to pin a feminist novel about our animal being to an abortion plot. While the narrator misrepresents the fact of her abortion to her parents and friends, there is no suggestion that the right to terminate an unwanted pregnancy is anything other than a right. Instead, the issue is made thorny and complicated – the question is not about rights and freedoms, but about how to endure life in a world made cruel by our being in it.

Women’s bodies are not tools or instruments, and legislating against a woman’s right to bodily integrity and agency is damaging to her personhood. Because she shifted the domain of the narrative away from what was, during the time of the book’s publication, a fierce and well-publicized debate, Atwood was able clear a path for her readers to think about the issue in a new way. She moved abortion away from divisive policy and headlines and into the realm of art.

Playing with the Canadian literary tradition of reckoning with the fearsome power of nature, Atwood’s Surfacing transforms these tropes into a dazzlingly accomplished consideration of how women, our bodies, and our fundamental human rights fit uncomfortably into an established tradition. Atwood takes that principally gendered discontent and builds it out into something rarified and noble, a new vantage point in the art form on what came before even as it broadens the horizons of what may yet be written.

There is a temptation to believe that the rights Dr. Morgentaler and a generation of activists fought for are folded irrevocably into an ongoing social project of liberation. “Because it’s 2016” was a common refrain among today’s young and entitled liberals in the same year that saw a drastic turn toward the far political right in Italy, France, the United Kingdom and America. People like me, sure, and people like the foursome depicted out in the woods in Surfacing, typically used this phrase without irony, implying that we have socially progressed to a point where shameful acts of institutional discrimination are stuck firmly in the past. The truth is that we have not, and that we cannot; the past, contrary to the cliché, is not a foreign country and nothing can be left there.

In 1988, the Supreme Court of Canada finally acquitted Henry Morgentaler of all charges against him. The ruling, handed down in accordance with the 1982 Charter of Rights and Freedoms, effectively overturned the existing legislation prohibiting abortion. Even so, access remains limited. The first legal abortion in P.E.I. has, as of this writing, not yet been recorded. Since 1988, women have had to travel out of province for the procedure. Last year was the first year in the province’s history that the government has mandated women’s access to safe, legal, abortions. A clinic was expected to open up before the year was through.

Last year, our American neighbours saw a law requiring the official burial of miscarried and aborted fetuses pass in Texas. A blatant attempt to legislate reduced access to abortion by any means necessary, the ruling came into effect in December, just months after the Supreme Court narrowly overruled the state’s right to directly reduce access to elective abortion. Across the Atlantic this past October, thousands of women wearing all black poured into the streets of Poland to demonstrate against a law that would completely ban all forms of abortion, the right to which is already severely limited in that country.

This is the context we live in now. And it’s in this context that I can unreservedly say that Surfacing remains an uncannily courageous, weird, and potentially explosive work.

—From CNQ 98, (Winter 2017)