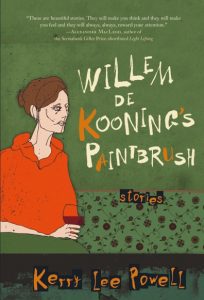

Montreal-born Kerry Lee Powell grew up in Antigua, Australia, and the United Kingdom. She has one book of poems, Inheritance (Biblioasis) and a pamphlet, The Wreckage. Her first book of short stories, William de Kooning’s Paintbrush, was recently published by HarperCollins.

Brad de Roo: Along with stories, you write poetry. Do these forms intersect for you? Does a poem ever start as a story or vice versa? How do you choose which form to proceed with?

Kerry Lee Powell: I write lyric poetry, and I’m very driven by voice as a fiction writer. When I come to see that there must be other voices to fully explore an idea, or a central tension around which several voices must revolve, a narrative that the voices must live through, then the work moves away from being a poem. But I don’t stray far. I love this quote from Stanley Kubrick: “The best plot is no apparent plot…the start that gets under the audience’s skin and involves them so that they can appreciate grace notes and soft tones and don’t have to be pounded over the head with plot points and suspense hooks.” We’re chronic storytellers — the art, or the poetry if you will, is in knowing where and when to linger. On the other hand, it’s easy to underestimate the skill involved in writing a decent thriller.

BdR: Are there authors who write both that you particularly admire?

KLP: There are some canonical writers, D.H. Lawrence and Thomas Hardy, and Sylvia Plath who write both and I would say those writers have been pretty formative. I’m drawn to lyricism, to writers like Virginia Woolf, Vladimir Nabokov, Henry James, J.D. Salinger, and Truman Capote, whose paragraphs and sentences often have the music and bravura of poetry. I’m particularly drawn to Nabokov’s lyricism, the way he navigates the follies and vanities of the self, his inner kingdoms of memory and imagination at odds with often preposterous realities.

It’s impossible to measure the debt that the literary imagination owes to poetry. The history of the western lyric poem is, to a degree, the history of western subjectivity. Even if you were create an arbitrary cutting-off point with twentieth century literature, distinctions between the forms collapse. The temporal shifts, the fractured vision of the self, those explorations of consciousness that T.S. Eliot made so richly explicit, the stunning poetry of Woolf’s fiction, these deep roots are still vital and flourishing in the works of fiction writers like Alice Munro, in poets like Fawzi Karim and countless others.

Kerry Lee Powell

HarperAvenue, 2016

272 pages

BdR: Trauma is central to many of these stories. The physical and emotional fallouts from violent interruptions of characters’ lives are explored in fine detail. What about trauma appeals as a conceit?

KLP: My father was in the Second World War and suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder and, after a couple of attempts, committed suicide when I was eighteen. Growing up with someone whose reality was so fractured by trauma, who was unable to overcome the horrors of a world war, has had an enormous influence on my work. Watching a fellow human suffer in that way sets you up, I think, to ask some fundamental questions about the world, and it creates a sense of alienation: How do people live? Perhaps I’m reliving his trauma through my characters, but I’m also, as an artist, looking for potential lyricism, for moments of grace that make survival possible.

Does art help to redeem us, or are we simply perpetuating violence? David Foster Wallace raised that age-old question when he condemned Brett Easton Ellis’ American Psycho, that it wasn’t enough to simply show that the world was horrible. But Ellis is a wonderful satirist, and American Psycho has a dark, fractured elegance that made a big impression on me as a younger writer. I find myself meditating on this argument often, in visual art, in literature, in the music of hip-hop artists like Eminem or Dr. Dre. As much as anyone might be outraged at the work, these are often superbly manufactured mirrors, manifestations of the late-capitalist self in its brazen paranoia and obsessive consumerism, its fierce marshalling of identity, its frightening dalliances with psychopathy. As a writer I’m also very interested in capturing moments of violence on the page, and I feel compelled to also acknowledge and explore that sense of ambiguity. Largely though, as you’ve observed, my interest lies in aftermath, in the repercussions of trauma. Salinger’s matchless exploration of post-traumatic stress disorder in Nine Stories has been a big influence on this aspect of my work.

BdR: Are stories integrally explorations of trauma?

KLP: In my last book, I wrote about my father’s suffering as a survivor of the Second World War, and I had “Father” with a capital F in mind because his experiences resonated so strikingly with the dominant myths surrounding masculinity in western culture: those of war and heroism, hubris and self-sacrifice. He was an educated man, often able to put his own mental disintegration into context, lining his shelves with books on war, quoting King Lear or passages from Homer’s Odyssey while he paced up and down the living-room floor. Sometimes he was violent, often he was inchoate. I don’t think any one of us is ever free, even in the most immediate physical sense, from trauma. To experience violent physical trauma is to become aware of the suffering of so many others, to experience momentarily the mortality that is common to all of us. I’m interested in the way trauma jolts us out of our everyday experience, sends us reeling into a primitive place in the brain where adrenaline and instinct overwhelm our more civilized selves, a shared underworld that is only glancingly knowable. There’s this absolutely seminal, to me, poem by Eugenio Montale called “Ossi di Seppia,” where a man is wandering through the countryside and turns to look behind him:

Maybe one morning, walking in dry, glassy air, I’ll turn, and see the miracle occur: nothing at my back, the void behind me, with a drunkard’s terror.

Then, as if on a screen, trees houses hills will suddenly collect for the usual illusion.

Trauma, for me, is a means of rupturing those “usual illusions.”

BdR: Your realistic characters often seek meaning and coherency through fantastical beliefs. They develop fairy-tale narratives or tell themselves occult or mythological stories. Do we tell ourselves such stories to escape the ugly realities of our lives? Do stories help with processing or healing traumatic events and/or abuses?

KLP: I’m interested in the ways that irrational belief systems continue to flourish in the face of what’s often called common sense. In many of these stories I aimed for a synthesis, something that was realistic, but that had the heightened, surreal qualities of fantasy. I was a Tolkien and C.S. Lewis junkie as a kid. Later on I gravitated towards writers like A.S. Byatt and John Fowles, who painstakingly recreate fairy tale, or fantastical or mythological worlds, but are equally committed to disrupting those worlds, interrogating that sense of enthrallment.

As a writer, as a reader, as a feminist, I recognize that fairy tales and a great of fantasy is often inherently conservative, reproducing cultural norms that are troubling, if not abhorrent. I went to the Philippines when I was eleven years old, a rich uncle paid for my father and I to stay in a fancy suite in the Manila Hotel, and I’d never seen such luxury before. While my father was out bar-hopping, I laid on a four-poster bed pretending I was a fairy princess in a castle. Later on I went for a walk, at the time the local officials in Manila had put up billboard-sized panels all over the tourist areas to block out the surrounding countryside. But if you went up and peered through the cracks, you saw these endless vistas of poverty and squalor, the shanties and clothes all the same colour as the surrounding mud. That crude method of concealment, those glimpses of squalor, the selfish relief I felt at once again closing the hotel room door, those experiences have stayed with me. One of the reasons that fairy tales enchant is that they tell the story of our selves, our innermost desires and primitive urges, the hope that we will somehow be chosen or saved, plucked from an otherwise formless sea of suffering and desperation. I wanted, in these stories, to lay bare both the allure and deceit of those narratives.BdR: A number of your characters are visual artists, especially illustrators. How does visual art inform your writing? Do you draw? Is writing at all like drawing?

KLP: I don’t draw outside the odd doodle, so I don’t know if writing is like drawing. I’m interested in art. I have a few friends who are visual artists or performance artists, and I taught creative writing for a while at an art college. I’m interested in the impact of personal trauma in a culture that commodifies violence, that often values intensity of experience and self-expression above, say, compassion. Visual art is one of the most vivid means by which these ideas can be explored. The artist Francis Bacon, when confronted by appalled critics, defends his often-horrific subject matter by saying “for a painter, there is this great beauty of the color of meat.” I wanted to explore that ambivalence, that domain beyond morality that we all at least partially inhabit.

Some characters in the book have given up on art, or reality, or are so committed to their own sense of aesthetics that they are blind to the needs of those around them. I was also really inspired by Yevgeny Zamyatin’s elegant dystopian novel, We, and by the works of J.G. Ballard and other dystopian writers, who use a variety of methods to expose the arbitrariness of what constitutes reality. I write about artificial environments, suburbs, and amusement parks, the sham worlds of nightclubs and the show homes of interior decorators: the worlds we create and re-create for pleasure or profit.

The collection’s title Willem de Kooning’s Paintbrush arrived after a few of the stories had come together. I was dating an animation artist for Warner Brothers who was a huge fan of the artist David Hockney. He’d worked with Hockney briefly on a project and had acquired one of his paintbrushes, which he’d had encased in glass and mounted on the faux mantelpiece of his walnut-panelled loft. I knew that I wanted to set a story in LA almost as soon as I arrived, wanted the juxtaposition between the fantasy-making apparatus of Hollywood and a tourist couple who undergo a random, brutal attack.

But my thoughts kept coming back to that paintbrush, encased in glass, resting on a little satin bed like Sleeping Beauty, and in my notes I kept confusing Hockney with de Kooning. The more I thought about it the more de Kooning’s brutality with the human figure, his extremism and his expressionism, all these things made his paintbrush seem like an appropriate talisman for a collection of stories unified by trauma, albeit a slightly inaccurate talisman, as de Kooning worked with various other tools. I’m referring symbolically to the violence of that gaze, and to work that seems almost psychopathic in its intensity, but that in fact requires a great deal of patient planning and ambivalence to produce. In the title story, I’m looking at the ways in which trauma dehumanizes both subject and onlooker. The woman confronts the ambivalence that her husband’s terrifying experience has produced in her. The comfortable life she’s made for herself is obscured, and Boyd comes into view as a figure in a de Kooning painting, fractured, barely human.

BdR: The performative aspect of clothing is a repeating motif in these stories. Characters often accentuate or alter themselves by wearing or shedding costumes. What about characters in costumes fascinates you? How is shedding clothing (like the strippers in certain stories) comparable? Different?

KLP: Studying medieval and renaissance literature, and particularly the dramas from those periods, has most likely influenced my sense of pageantry and spectacle, the role that clothing plays in determining our identities, our gender, and our social status. Unclothed, we are vulnerable as individuals. But the nude figure in art is seen as “universal” whereas the costumed figure is always constrained by its historical moment. Clothing, and the freedom we have in donning masks or costumes or disguises, is to me a symbol of the fluidity of the human imagination, of inner lives that don’t or can’t respect the boundaries and inhibitions our various cultures place upon us.

BdR: Immigration, immigrants, travel, and xenophobia are consistent concerns in Willem de Kooning’s Paintbrush. Do you see fiction as a means for cross-cultural empathy? How much have your personal travels influenced your writing? Does your reading reflect an interest in this diversity?

KLP: I moved around a lot as both a child and as an adult. When you move often, you’re forced to deal with the tribal prejudices of locals and undergo the rituals of establishing yourself in any given pecking order. You become aware of how contingent value systems are.

In Canada, many of us from diverse socio-economic backgrounds aspire, or are encourage to aspire, to a middle-class lifestyle that has fairly rigid parameters, prescribed modes of behaviour or self-expression. Some of my characters are immigrants, some are people who feel like imposters in familiar environments. I set each of the stories in a different geographical location because I wanted the world of each story to disrupt the world of the last.

I write largely from the perspective of a white female, but I want my reader to be distracted by the urgency of other voices. And of course there’s a whole literature of alienation and exile that I’m consciously and unconsciously indebted to, works that explore absurdist and existentialist philosophies, and other works born out of the mass migrations of people whose lives have been shattered by despotism or war. I’m not sure if I do see fiction as a means for cross-cultural empathy. Or maybe empathy isn’t enough. Many of us, when confronted by or exposed to the enormity of suffering, to the trauma of others, can do no more than turn inwards, or away. Literature is a source of escapism and pleasure. It creates worlds but it also shows the world as created, by our own values and ambivalence. For me, the tacit implication underlying any work of art is that we’re not governed by fate, that we can change our minds, our lives, our worlds, hopefully for the better.

May 25, 2016, CNQ Web Exclusive