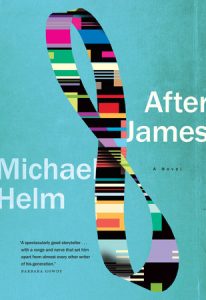

Michael Helm’s novel After James (McClelland & Stewart) was published this September to widespread critical acclaim. Ambitious and virtuosic, it’s a story told via three distinctly different but interconnected novellas, each with its own geography, genre, and characters, the complex common thread being the titular “James.”

Brad de Roo: After James is essentially three novellas that resonate together. What appeals about the novella form?

Michael Helm: It’s elastic and manifold. There’s not much in common between, say, [William] Gass’ “The Pederson Kid,” those weird things César Aira writes, Point Omega, Yuri Hererra’s Signs Preceding the End of the World, and Anne Carson’s hybrid fiction. But I wasn’t thinking of three novellas so much as one novel made up of other novels. Maybe it came about because story forms like 2666 and Keislowski’s Three Colours trilogy are out there, but it’s not much like them. I guess I wanted something I hadn’t seen before.

by Michael Helm

M&S, 432 pages

BdR: Did you start out with the intention of compiling the three stories into one overlapping whole, or did the form arise via the writing? Were there any other stories that did not make the final arrangement?

MH: I wrote the three parts concurrently and understood early that they were connected and saw the order and shape. The writing had complications in three dimensions. It took time to find the right tonal shifts, keep certain questions before the reader, create resonances, and keep the whole thing moving forward while the patterns and themes, whatever, began to bring the parts into a certain relation.

I didn’t have other stories beyond these. There was no thought of setting something in the distant past or future or on the planet Zorgon.

BdR: Being a fan of literary genre-mashers like Michel Faber and Brian Evenson, I was very pleased with the presence of many genres in your book. I was even more pleased with the hybridization of genres that occurred within particular novellas. Is your extensive use of genre a rebellion against any particular way of writing? Is genre being taken seriously enough in CanLit circles?

MH: I’m kind of in CanLit but not of it. I don’t know much about CanLit circles but apparently After James moves around happily in the territories outside of them. I don’t write in rebellion. I just write what I want to read.

Genre as both subject and form first started to matter to me when I wrote In the Place of Last Things. The idea was to make a novel as if it were a sketch of one creature composed of others, drawn with one continuous line, in sort of unfolding conversions. That novel was slightly subversive of genre understood in the sense of sub-traditions – the road novel, the campus novel, the love story, a kind of crime novel, and others.

I read genre fiction, mostly crime novels, of the kind that are safely outside the world as it is and don’t pretend to be saying much about real history or politics. But somewhere behind After James is my anxiety about certain kinds of genre entertainments, especially of the kind where women are imperilled or go missing or get objectified against their will. I’ve had my fill of TV shows, however well written or acted, where every episode or two the camera takes time to pause over dead naked young women. If something can be boringly offensive, that’s it. Fifty years ago, Leslie Fiedler identified two possibilities for the gothic in American literature, a distinction that seems to me still relevant to that genre. One is “the pursuit of genuine terror” and the other is the “evocation of sham terror.” One is a “confrontation” with violence, the other an “indulgence” in it. Without relenting entirely of genre conventions, from its opening to its ending, After James attempts to draw readers into its pages through “sham terror” yet to bring them to a confrontation with real trouble. The trouble comes in forms sometimes used in escapist fiction but that should now belong among the concerns of serious literature: climate change, mass surveillance, death-cult terrorism, bioweaponry, or just this new kind of disquiet in the air.

The danger is that the writer might hide behind ironies to get away with using the very tropes he’s taking on or taking down. In Cities of Refuge one of my characters, a woman who’s survived real violence, sees a painting by Gerhard Richter of a woman who ended up murdered, and she wonders if the amazing artwork isn’t just another instance of a male artist being sly with violence. I like that she thinks to ask the question, and that yet she’s amazed by the genius of rare artistic talent. In fact, now as I’m answering this question I realize a variation of this occurs in Part II of After James, when the narrator, James, remembers his ex criticizing a Velasquez painting for the political conditions that brought it about. James understands what she’s saying but can’t really get past the sheer virtuosity of the artwork.

I seem to have drifted from your questions.

BdR: Literary investigation fills your book, especially the second part, “Décor.” Semiotics, deconstructionism, etymology, hermeneutics, and other fields of literary theory make explicit or subtle appearances. Are you prone to view your own work through these means of perception? Does a story that doesn’t directly explore how it’s a story miss out on an important dimension of reading?

MH: I’m not aware of having consciously used much literary theory, but certain ideas interest me, of course. They have to really inhabit me before they register in the fiction. I try to write without a thought in my head so that such thoughts as there are come from the toes, having sunk that deeply.

I do seem to be interested in there being some self-awareness in the writing. I love the very best realist novels maybe more than I love the best metafiction, but why not aspire to a fiction that presents as realist in one light and as ironic or self-aware when you turn it? We’re all struck with self-awareness. Fiction needs to be adaptable to the ways this self-awareness makes claims on us, and it does so differently in this century than it did in the last.

In one of his letters, Italo Calvino writes, “Man is simply the best chance we know of that matter has had of providing itself with information about itself.” I would say that fiction is the best thing we’ve come up with for understanding our condition of being aware of ourselves. It’s fundamental to nature, even material nature, to reinvent itself constantly based on what it knows of itself, trying to get things closer to right (which means only, right in the given moment). There’s a degree of self-awareness even in the coursings of invisible things.

BdR: After James deeply explores technology’s ability to redefine and reframe a human sense of self. Biotech, pharmacology, and digital communications all figure as diverse agents of self-reformation. Characters often struggle to make heads or tails of their identities in this perceptually enveloping mix. What does a well-integrated self look like, to you, in this constant shift and onslaught of mediated experiences? Do any particular elements of modern technology frighten you? How has the multifaceted growth of technology in our day to day affected your writing process?

MH: These technologies do a number on our ability to find the borders of the self. The last word on the self is always physical but the second last one is emotional, and through technologies the emotional self extends beyond us in ways we can’t measure or can only mis-measure.

Since the novel came out I’ve been asked about apocalypse and dystopia. I don’t read a lot of dystopian or apocalyptic novels, but the best of them are both wildly imaginative and dead serious. Dystopias exist now in parts of Iraq and Syria and elsewhere. And the danger of global apocalypse is real and growing. Climate change is killing us and many other living things. New plagues are going to emerge. Nuclear and bioweapon stockpiles aren’t secure. The internet isn’t secure. What do we call the condition where we know this stuff but can’t get enough people to care? The sky really is falling. We’re expected to suck it up and adjust.

So that affects my writing process, this pitch of doom. And of course, just practically, interconnectivity allows far too many voices into any room. Novels take a long time to write. They can’t be written while carrying on five conversations. There used to be a chance for enlightenment in asking someone to tell you what they were thinking. Now they’ll tell you anyway, without being asked. I want to say, “Don’t tell me what you think. Sit with it a while.” There’s a reason my closest friends fall quiet for long periods of time. Silence can be scary but in time it calms the jitters. Then, if we’re lucky, vast prospects open. Somewhere out there, maybe we’ll find ourselves.

BdR: The study of genetics is readily and regularly invoked for its metaphorical and symbolic richness in then novel. What about genetics is creatively inspiring? Do you note specifically vibrant analogies between its modelled forms and those of art?

MH: Let me say, first, that I’m an idiot about this stuff, but I have scientist friends who are not and who patiently explain to me genetic processes, the science, its implausible applications, the ways our understandings of pasts have been changed or junked by new findings. Genetic science is attractive for its power to rewrite assumptions about life in all forms. When we speak metaphorically, comparing literary and organic forms, it’s no step at all to think about transference from form to form, or about extracted codes and mixed codes, and these feed into ideas about literary form and non-organic systems, maybe most obviously computer and internet technologies, but not just those.

BdR: Surveillance is a central concern of the book. Many characters are under constant suspicion of being surveilled, or of surveilling. The literary minded in “Décor” are often shown to be implicated in both sides of surveillance. What are the dangers that beset an author in age of increasingly insidious monitoring? Is there anything about a writer’s need to watch and keep tabs on people that borders on surveillance?

MH: I wouldn’t make statements on behalf of all writers, but I don’t think of myself as a keeper of tabs. I watch in order to see, to understand, or maybe to find something, a certain shape or gesture, that I never will understand. It’s an under-accounted for part of the practice, I think, this watching. The world streams by – live or mediated – and we can’t take it all in, so our attention becomes selective. If it narrows too much, then it’s not attention, but the trap of the habits of mind. I love being in the company of someone who sees other than I do, who catches different things in the scene I’m looking at.

But now we’re all being forced to conceive of a thing there’s no picture for. Full-on Big Brotherism used to be associated with the classic totalitarian state, but now the sources of intrusions into private lives have become both more powerful and less identifiable. Governments, certainly. Corporations. But also other citizens. Any or all could be watching us. One of my friends has seen a demonstration of real-time identification of a presumably anonymous internet searcher. From the data stream some anonymous user searched for tattoo parlours, four locations around Houston, Texas. The search narrowed to neighbourhoods around the location of the parlour sites, and through IP addresses, server locations, associated searches, and who knows what else, the tattoo searcher was identified – name, address, age, and so on –with a 99% probability, within two minutes. And by the way, we can imagine only a zillionith of the implications of giving over our genetic information to a corporation. You only want to know if you’re part Neanderthal, but because you click-signed the waiver you didn’t read, your info can be sold, used to track you, sell things to you, manipulate you and your offspring in the future in ways we can’t predict.

BdR: The apocalyptic opens its ugly maw throughout the book. Visions of plagues, storms, floods, and wars abound. The final section, “The Boy in the Water,” is consciously eschatological. What about the apocalyptic makes it a persisting conceit, an authorial tradition? Do we live in conclusively apocalyptic times? Must an honest book end grappling with end?

MH: In the sense of an obliterating revelation, apocalypse happens all the time locally. In some place or another it’s happening right now. But even globally, all times are apocalyptic in the mind or the nerves, as the history of millennialism and its attendant forms proves. Theologians and cult leaders tend to get their math wrong, but the feeling persists. For about seventy years, it’s been possible to know one of the forces that could bring about the kind of destruction to make way for the better thousand years we’ve all been waiting for. And now the threats are multiplying. Last year The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists moved their doomsday clock another minute closer to midnight based on their assessments of the security of mega-weapons and the by now fatal inability of our species to deal with climate change. Our anxiety about entering the end times has been used against us. The anxiety damages the wellbeing of anyone awake to things as they are. The deranging effect of impending harm or death is evident in the breakdowns of some of those people living under armed drones, as reported by the social justice clinics at Stanford and NYU and by those captured by the Taliban. But we’re all under a shadow that feels like a dark promise.

But all this makes the novel sound more doomy than it is. I wanted it to have as full a range of registers as possible. Humour, irony, love, resonating strangeness, hope. I wanted these things for the novel, so that by the ending – the novel’s ending, not ours – all of them are in play. And play, for that matter, I wanted that, too.

—A CNQ Web Exclusive, November 2016