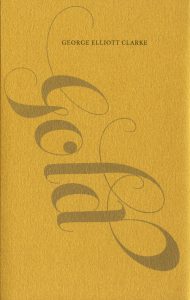

by George Elliott Clarke

Gaspereau Press, 160 pages

If I had been asked to hand out medals to Canadian poets at the starting blocks of the new century, George Elliott Clarke would have been a contender for gold. Back then his verse was kinetic, and reverberated in the national consciousness as if it had been looped through a stadium-sized boombox. This supersonic articulation, along with his broad-minded social conscience and formal acumen, made Clarke a maverick among his contemporaries. Indeed, his closest Canadian forbearer is Irving Layton — a modernist who, among other shared qualities, favoured poems of verbal excess. Paralleling Layton’s early assumption of mastery, Clarke took up the mantle as Canada’s perennial medal hopeful upon the publication of Whylah Falls in 1990. Introducing the elaborate unofficial history of an entire “Africadian” community, the book grapples with unrequited love, poverty, and racial injustice, and is one of the country’s most ambitious literary touchstones.

Poetic forbears often teach us what to do and what not to do, and some of Layton’s less-desirable characteristics endure in Clarke. For example, the more Clarke publishes, the more his proclivity towards repetition exposes the prescribed characteristics of his work — ecstatic rhetoric that originally felt fresh now feels played out, and predictable diction has dulled his lively syntax. Though he seems to rise in stature with each passing year (Clarke is currently the Parliamentary Poet Laureate of Canada), new books have been hastily published, and on the whole, ill conceived. Traverse (Exile Editions, 2014), a book that represents the nadir of Clarke’s Layton-like over-production, was apparently written in a single day. While Whylah Falls is still Clarke’s gold standard, his most consistent offerings in recent years have been his self-described “colouring books” — Blue (2001), Black (2006), and Red (2011). Gold (Gaspereau Press) is the fourth book in the series, and gives Clarke a chance to reinvigorate his oeuvre, if not his craft.

So, can we call it a comeback? Based on the first poem in the book, “Duplicity”, the results are mixed. Beginning in halting iambic pentameter, the poet pens a self-portrait:

Two-faced poet? That’s me. “Guilty”—as framed.

My double visage suits my double tongue—

Spieling out twice-told tales in spliced duets—

Paper-and-ink, print-on-a-screen—unless

I redouble lies by dubbing aloud.

Let’s say my art’s “Romantic,” so I sport

A rosy halo—like printers’ devils,

And blaze all night, steeped in rosé or blush

(Bed) sheets…. Or say I’m extra “noir,” extra

“Polar,” my face pairing disappeared heart—

AWOL, paroled, sentenced no more to Love….

Or say my background’s orange—a hint of sun:

It gilds “Apollo”; suns appalling Guilt.

This triptych of twin selves tells I’m split—

North, South, East, West, Hyde-and-Jekyll; thus, each

Ensemble disassembles—in resembling me.

As if caught in a lie, Clarke deliberately adopts a stop-and-start pace: “Two-faced poet? That’s me. “Guilty”—as framed.” Pausing to admire his work on “framed,” he then repeats himself (two-faced / double visage, double tongue / twice-told tales) while moving forward with his argument, hammering home the speaker’s unreliability before a sudden switch from iambic to trochaic pentameter signals a turn. This is Clarke in full control, shaking the reader awake when he shouts: “I redouble lies by dubbing aloud.” Alluding to his public readings, which have an exuberance that rivals his verse on the page, Clarke uses this line to transition to the poem’s volta. Strangely, “Duplicity” ’s sluggish meter is maintained here, despite the opportunity for a knockout blow. Stranger still, Clarke tenders a “triptych of twin selves,” spending little time to develop his case, choosing instead to let a series of images — printers devils, rosé bed sheets, a disappeared heart, Apollo — pile on top of one another until the poem is cluttered with underdeveloped ideas. By the time he invokes Jekyll and Hyde, the portrait feels like a potentially great piece of art that’s been overwrought, its best qualities squandered.

“Duplicity” sets the tone for much of the book. Clarke is a brilliant, if inconsistent craftsman, but his maximalist bent often blunts his superior technique. Bigger is better in Gold, and this extends to the ephemeral material that pads the book out to an unruly 150+ pages. Here the reader will find a trove of images scattered in the “Gold Mine” (as Clarke dubs the collection’s contents), some of which function like visual poems themselves. For example, to counter the formal framework of “Duplicity,” a photograph of the author cleverly flanks the poem, appearing on the left-hand page. Clarke’s duelling, Janus-like self-portraits present the reader with a literal “double visage” — artist and art — that enhances the mnemonic qualities of the poem. The technique of pairing photographs with verse is a hallmark of Clarke’s “colouring books,” and continues throughout Gold, giving it visual resonance with past work.

Yet attempting to fulfill Gold’s status as a sequel is part of what prevents Clarke from making it new. In “Golden Moments,” a poem patched together with a series of statements that begin “Gold is…” (preceded by “I. i” in Blue, “IV. iii” in Black, and “Other Angles” in Red), Clarke constructs a rationale for the colour that brands the book. While this formula was one of the highlights of Blue, it proves rote fifteen years on, and “Golden Moments” is problematically executed with a veritable rainbow of adjectives — emerald, white, black, red, purple, silver, grey — to describe the gold within. The hit or miss quality of the poem is also reinforced with lazy lines referencing other sequels like “Gold is Goldfinger, Diamonds are Forever, and The Man with the Golden Gun.” Relying on his reader’s sensory experience of well-known books/films, Clarke adds little value of his own by namedropping rather than tendering fresh commentary on 007. Regardless, the poet’s “colouring books” are more akin to Die Hard than James Bond —pyrotechnic, over-the-top, and increasingly thin on plot — with Gold languishing in a line of action-heavy follow-ups.

Clarke is better when his verse swaggers, as in “Austin C. Clarke’s “When He Was Free and Young and He Used to Wear Silks” (1971): Subtext.” Boasting the author’s signature sonic fluency, the poem was penned for “A Celebration of Austin Clarke” at the International Festival of Authors in 2015, and follows a protagonist named “Clarke” over the course of an evening at Toronto’s Pilot Tavern. It also includes a swathe of the most dexterous prosody the poet has put to page:

The feministized divorcée returned.

My lungs changed chords.

Preening amid smoke and Smoky Robinson—

his meddling, wah-wah cries,

this independent woman surveyed, for me,

the Eliotic Waste Land that’s Divorce,

while I spilled down precious fluids

in unbroken ripples,

and the lady sucked sexily at her drinks,

secreting, now and then,

the gaseous piss of a pregnant silence.

These lines are a prime example of Clarke’s inimitable style — a powerhouse display of alliteration (“changed chords,” “sucked sexily”), consonance (“gaseous piss”), and onomatopoeia (“wah-wah”). Moreover, he audaciously weaves Smokey Robinson, T.S. Eliot, and a Beyoncé song title (“Independent Woman”) into a scant four lines before turning a round of drinks into a snapshot worthy of a Harlequin romance. With the technical details behind his widescreen ambitions on full display, Clarke draws the poem out for a full twelve pages. Barring a bathroom break, nothing of consequence materializes in the plot — the speaker enters and heaps superlatives on his drinking companion, content to simply muse about where the evening will take them. “Clarke” ’s entrance to the tavern is even described twice, as he backpedals to sketch “the slinky, leggy lady” he meets in gratuitous detail. I’d call this a Rashomon-like retracing of steps, only Clarke doesn’t change perspective, he just pens the poetic equivalent of a double-take.

While “Austin C. Clarke’s ‘When He Was Free and Young and He Used to Wear Silks’ (1971): Subtext” is a linguistic achievement, it’s also symptomatic of Clarke’s increasingly problematic portrayal of women, particularly in books like Illicit Sonnets (2013) and Extra Illicit Sonnets (2015). Similar to Layton before him, Clarke has always pushed the boundaries of good taste in relation to sex, but there are several instances in Gold that are palpably hateful. As the speaker at the Pilot Tavern gets drunker, he becomes boorish, imbuing his companion with “bitchy intelligence,” and fantasizing about “pry[ing]her saggy or stretchable snatch / until she[‘s] haggard”. The violent details don’t end there, and Clarke continues to reduce the interaction in question to “[w]ill she or won’t she? That’s what matter[s].” Early on in Clarke’s career, his transgressions were more salacious than misogynistic. Consider the blues-based love song, “To Selah,” from Whylah Falls:

The butter moon is white

Sorta like your eyes;

The butter moon is bright, sugah,

Kinda like your eyes.

And it melts like I melt for you

While it coasts cross the sky.

The black highway uncoils

Like your body do sometimes.

The long highway unwinds, mama,

Like your lovin’ do sometimes.

I’m gonna swerve your curves

And ride your centre line.

Stars are drippin’ like tears,

The highway moves like a hymn;

Stars are drippin’ like tears, beau’ful,

The highway sways like a hymn.

And I reach for your love,

Like a burglar for a gem.

Here Selah’s suitor is lustful but loving. There’s menace — the poet is describing a forbidden affair — but the poem’s central images (the butter moon, stars, tears) are traditionally Romantic. Even the crude metaphor at the end of the second stanza —“I’m gonna swerve your curves / And ride your centre line”— is couched in bluesy repetition, with the surrounding bandwidth reminiscent of a calm drive. Now counter this with the divorcée’s monologue in “Austin C. Clarke’s ‘When He Was Free and Young and He Used to Wear Silks’ (1971): Subtext.” Describing herself as “acting the couch-surfing adulteress, / a no-mind, nomad, no-one-man’s slut,” she is rendered less an independent woman than a thinly sketched character acting out the author’s fantasies. The self-deprecation above is disturbing, and while degradation is part of the duplicity Clarke strives to explore in Gold, it’s too common in his new work to be ascribed to a single character.

This is particularly evident in “Gold Heart,” the series of “Sapphics” that act as the emotional core of the book. A liberal sampling finds Clarke reeling off vitriol like “Unsheathe your slick, orgulous instrument, / Pickle it in the snacking gash” (“Desolazione Cosmica”) and “the fine-ass, small-tit wench shakes as if / Martha Beck, quaking her electric chair” (“Mariangela E La Seduzione”) — lines as bilious as they are blatant. They’re also repetitive, and vary little in rhetoric or tone. Which is unfortunate, because when Clarke broadens his scope, as he does in “Oreo Blues,” very few contemporary poets can match his follow-through. Like “To Selah,” “Oreo Blues” describes an illicit relationship, set in an era similar to circa-1920s Whylah Falls. Both personal and political, its stanzas are incisive, as in this excerpt:

I feel lonesome as a flower,

Glorious in a desert!

Like a Qur’an in a liquor store,

I’m misplaced; I’m dissed; I’m hurt.

My gal sucked all my gusto;

I’m like Autumn-cut-down August: Curt.

According to Gold’s extensive notes section, these lines were composed on a flight from Barcelona to Toronto in 2015. Plunking the reader down in a hostile, racist desert, “Oreo Blues” is more pluralistic than the rest of the poems in “Gold Heart,” and Clarke’s language is urgent, matching the exigency of a situation where the speaker has been misplaced, dissed, and hurt. This urgency is peppered with bravado, however the invective displayed in “Desolazione Cosmica” and “Mariangela E La Seduzione” is now warranted, transformed by the profound sense of fear that builds throughout the poem. It’s easy to imagine the speaker running — “If we’re caught out, see me go— / Spectacles, Swiss watch, suitcase” — despite his declarations of love.

In the end, Gold feels like an unnecessary entry in Clarke’s rapidly expanding oeuvre. For a poet who once aimed “to take apart Poetry like a heart,” he’s now firmly on autopilot, publishing rapid-fire collections that serve as stopgaps rather than showstoppers. It’s not surprising then that Gold isn’t Clarke’s only release of 2016 — he began the year by delivering a novel (The Motorcyclist) and will end it with a 400+ page epic poem (Canticles I) that will spawn more sequels. In “Upon Reading Flavia Cosma’s ‘Thus Spoke the Sea’” Clarke writes: “We all read Literature badly: / We think it is cabalistic Scripture.” He’d be well served by heeding his own admonition — where he had a legitimate claim to eminence at the turn of the century, Clarke currently runs the risk of becoming a standard bearer for overindulgence, of mistaking much of the work he publishes for gold.

—CNQ Web Exclusive, November 2016