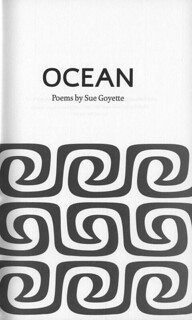

Sue Goyette’s Quagmire

Sue Goyette

Gaspereau Press, 2013

80 pages

The crux of the discussion so far about Sue Goyette’s Ocean has been its placement in an appropriate tradition. Chad Campbell, writing in Maisonneuve prior to the book’s Griffin Prize nomination, found it full of “poor metaphors and rickety conceits.” He goes so far as to summarize the vehicles used in an excerpt from “Forty-Four” (the poems, identified only by number, are not titled), in order to show how nonsensical the metaphors are. Phil Hall, in response, misreads a good part of Campbell’s review – for instance, he thinks that Campbell uses the word “metaphor” contemptuously, when Campbell clearly has a problem only with Goyette’s sloppy use of the device; and that Cambpell’s neutrally descriptive summary of the book as “a chronicle of a society undergoing feverous and protean changes” is meant as a criticism – but he does make a point worth engaging: Campbell was myopic in dismissing Ocean on the basis of its imprecise metaphors. Campbell has evaluated the book according to a more formal tradition, or by using what Hall calls an “academic method.” “This poem,” Hall says of the piece whose metaphors Campbell dissects, “does not come out of the tradition that is being used here to judge it.”

In a CBC radio interview, Goyette urges readers of her book to “just be in the ocean”; “people,” she remarked, “will either get it or they won’t.” Implicit in the pronouncement that the reader must just “get it” is an opinion that someone who does not like or appreciate these poems could not be convinced to do so. Hall’s review exhibits a similar logic – namely, that a rational point–evidence–argument model won’t work here. His review is composed of clipped, one-to-three sentence paragraphs, and groups of paragraphs are separated by ellipses: an alternative to “the academic method,” or “systematic quoting to support a thesis.” Of course, the problem with ditching systematic quoting is that his points, lacking supportive evidence, have little power to convince.

Hall urges you to “jump” into the book, and when you do, you land in a boatload of strange analogies. Gaspereau Press presents the book as a biography of the ocean, and the ocean is the thing most often metamorphosed. The ocean is sometimes just “it”; at other times it is: a fashionable accessory; a beast; a cook; a mood ring; a failed experiment; a dominatrix; a form of currency; part landlord, part wolf; a furrowed brow; a pacing waiting room; a coyote; a caged animal; a wild lover; a reckless friend; a lion; an audience; a performer. When listing the metaphors this way, it’s not hard to see Goyette’s point: the ocean is changeable, impossible to pin down, but we’ll try our best to understand it, through whatever means necessary.

What you can’t tell from this list is how well or poorly the metaphors work within their poems. Goyette’s main strategy is to introduce a figure, only to veer wildly from it. For example, “Fifteen” begins:

We grew alarmingly quiet the years we believed

our heartbreak had made the ocean salty. We had foundlove like a box of candles beneath our beds . . .

We had no idea how love would go on to build its fires

in our every word.

And continues:

How it’s a factory that churns out action

in a way that our city wasn’t used to.

Oh the high school musical of a smile. The conquestand lasso of a kiss. We learned to play the fiddle

in those days. . . .

Or “Twenty-Five,” which starts with a perfectly well-developed metaphor:

Someone had figured out how to grind up footprints

and then sold them by the gram. It only took snortinga few lines to wake up a homesickness we hadn’t

experienced before. This elicited its own kind of hangover

Only to lose us at the next simile: “that made our feet feel like tired tongues.” Non sequiturs like these abound, as do metaphors that switch vehicles with no apparent logic.

Perhaps dismissing the whole book on the basis of its illogical metaphors is, as Hall contends, unfair. As he points out, Goyette belongs to a tradition whose poetry “hurls a reader along, past logic,” although her poetry is not as rare or radical as Hall makes it out to be. In fact, poems whose metaphors aren’t overly logical seem to have become fairly common, though Goyette’s do seem wilder than many. Michael Oliver, reviewing Ocean in The Antigonish Review, argues that Goyette’s central thesis is that “inarticulation is a trait the lonely ocean shares with human beings. There is logic in this argument – poetic logic, but this is a poem!” I’m not sure what he means by “poetic logic,” but, unfortunately, inarticulateness overwhelms the poems. Inarticulateness seems more a problem with the poems themselves than a problem they are trying to inscribe. The poems’ articulation issues are compounded by a host of other faults. Invariance of form, while perhaps making a point about the ebb and flow or invariance of the ocean, becomes distressing. Every poem is set in a series of long-lined couplets, a good chunk of which are heavily enjambed. After a while, the line and stanza breaks seem arbitrary. A quick glance at her past work will show a similar invariance, which makes the structure seem more like a default setting than something insisted upon by the poems’ subject matter. It’s hard to make sense of a form that is quite loose but that doesn’t vary. It’s also hard to find meaning in the unwavering use of the preterite tense. It’s there because, as Jeffery Donaldson points out, Goyette is writing in a mythopoeic mode, a point to which I’ll return. But verbs in the past tense that continually appear in constructions like “we weren’t,” “we invented,” “we grew,” “we didn’t want,” “we went,” etc., quickly become predictable and therefore uninteresting.

There are a few streams running throughout this book: 1) ocean as beast; 2) desire/longing; and 3) a backward glance, but magnified to the level of myth. Donaldson has conducted a very helpful close reading of “Eight.” He points out that Goyette is writing in the tradition of the “contemporary inheritance of the mythopoeic,” in which, as he says, “the very weird and the very actual” happen in the same poem. Donaldson also aptly points out that the book exhibits a uniquely Maritime attitude, which he defines as “skepticism toward the monumental itself,” both “humble” and “savvy.” This attitude is the most coherent thing about the book. But the last two streams, 2) and 3), don’t mix well, and this incongruity is even more of an obstacle for a reader than the murky metaphors. A sudden expression of desire or longing jars when it’s stuck in the midst of a primarily mythopoeic poem. For example, in “Forty-Five” and “Forty-Six,” which appear on opposing pages, a few phrases appear that use a formula against which Ezra Pound warned – “the concrete noun of abstract noun” – because “it dulls the image”: “Oh the coniferous tears / of our pining”; “the fish hooks of our goodbyes”; “a gypsy of kisses” (“Forty-Five”); and “the teddy bears of their bedtimes” (“Forty-Six”). Beyond alienating readers by, without warning, taking them out of one mode and dunking them into another, these individual, private emotions – desire, longing – are presented as collective, and, unless all individuals are also experiencing these expressed emotions, the effect is unproductively alienating.

Part of the “other tradition” in which Goyette writes is that of political poetry. She has said, “This was for me a political book.” She’s also said, “But to be political you have to be so hospitable.” I wish she had been less “hospitable,” because her hospitality translates into unhelpful imprecision; the poems are best when their concerns are clear, and when the vision they present isn’t obscured by fogs of nonsensical metaphor. Five poems from the end of the book, the ocean departs, leaving us with a sealess Halifax: “We woke one morning and the ocean was gone” (“Fifty-Two”), an event that clarifies the book’s (albeit loose) narrative arc. The post-ocean poems tend to have more tangible images, and are better at building up coherent worlds, as for example: “We tuned our radios to the sunsets and downloaded / whale call overdubbed with protest songs” (“Fifty-Five”). Or: “We wanted pure ocean podcast into our veins but tethered while we slept,” which works well with the funnier tone of a line in the same poem: “We wanted death to be a stranger we’d never have to give directions to” (“Fifty-Five”). In the last poem, the speaker switches to the second person, and this mode of direct address works so well one wishes she had written in it earlier and more often:

When it whistled, whatever is in you

that defies being named, didn’t that part of you perk up?And didn’t you let it tousle you to the ground,

let it clean between your ears before it left you?Wasn’t that all right? That it left you? That we all will?

Goyette is obviously not without talent, and she definitely has a vision, which is apparent as early as her first book, The True Names of Birds. Her past books were a bit more formally rigorous, and the slightly weird metaphors worked better: there’s a sense that something is being left unsaid, and the poems are eerie without being alienating. The thread that works least well in Ocean is also present in the past books: that individual-presented-as-collective longing and despair, apparent in a general overuse of the throwaway abstraction “loneliness.”

On the one hand, Ocean is concerned with such individual anxieties; on the other, and more largely and explicitly, it’s concerned with origins, invention, the mythology of the ocean, ritual, and the psychological effect of the sea on individuals and society. The book, however, does not accomplish what it sets out to do. Its vision is lost to readers, who encounter confusion where it doesn’t seem intended. Donaldson points out that the central emotion of “Eight” is anxiety. This anxiety is sustained throughout the book and, frankly, it’s exhausting, not to mention hard to navigate. The problem with jumping into this book is that the water is in fact a quagmire.

From CNQ 92 (Spring 2015)