by John Miller

Cormorant Books, 296 pages.

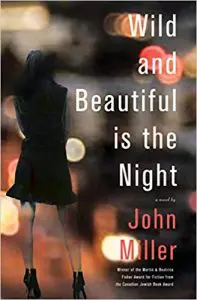

The most inviolable cliché of writing sex work is that the published product must always be accompanied by an image of a faceless woman in heels. While John Miller’s newest novel—Wild and Beautiful is the Night—certainly has the cover of a Pretty Woman novelization, the book is so ambitiously and fastidiously empathetic in its execution that I almost took the cover image in the snide spirit of the art on Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels. In other words, as a warning that your biases are cute but that they’re not this book’s problem.

As often happens when men write about sex work, the author’s primary concern is moral. In this case, though, Miller is preoccupied with the ambiguities of appropriation. From the first few pages, as our narrator, Paulette, weighs how best to relay both her experience and her friend Danni’s—tell it straight? or rabbit around like Danni herself would?—Miller is cautious and self-aware. His acknowledgements detail extensive research, and a recent column in the Globe and Mail (entitled “How far will writers go for our craft—and at what cost?”) eulogizes the former colleague who granted him several interviews, knowing he’d use her experiences as material.

“Using” is the word writers say when they’ve struck oil. “I’m using that.” “Can I use that?” We are capable of using other people’s pain like painters use paint. Here, it has other connotations. Both of its main characters are street-based sex workers managing crack addictions. Any one of the book’s plot points—poverty, homelessness, jail, rehab, relapse, assault, single motherhood, abortion, HIV—could fuel most Canadian novels for three hundred pages. Paulette, whose parents were Jamaican immigrants, is gay, and lost her first daughter to Children’s Aid years before the story starts. Her friend Danni is an upper-middle-class Jewish girl with a degree in women’s studies and a pill habit stemming from childhood sexual abuse. You see how the question of appropriation becomes inevitable; where, exactly, is the line between bearing witness and pain tourism?

Miller is a goal-oriented novelist, moving cleanly through five years of emotional and environmental extremes most of his readers will never face—and nary a confusing tense change, despite Paulette’s early anxieties. He doesn’t indulge in showy line work or poetic obfuscation. All the usual scuffs that mark a novelist’s ego are effaced. Even the occasional slip towards homily—Danni on not disclosing her HIV-positive status to her clients: “I gave them three clear reminders about condoms. Are we their fucking mothers? Are we the fucking health department?”—is a canny rendering of politicized minds, rather than pedantry at their expense. At times I wasn’t sure where the satisfaction even comes from for Miller: he seems to barely exist in his own work. He’s so self-restrained that the book could read like an act of service to atone for the temerity of having written it. I’m moved by this humility.

The day before I began work on this review, sex-work Twitter was raging: a teachers’ conference in Calgary had hired a recovered addict named Andrew Evans to share his “message of hope.” In 2006, Evans was high and drunk when he strangled Nicole Parisien to death because he was unable to get an erection. He spent seven years in jail for killing her. When local media outlets questioned the choice of speaker, conference organizers doubled down (teachers are critical thinkers). The next day, national papers picked up the story, and the organizers cancelled Evans and his honorarium. I mention this because when men who murder a certain type of people are consequently invited and paid to tell the story, questions of appropriation go from shrill to siren.

Writing in Room, Alicia Elliott recently proposed a basic guideline for writers worried about appropriation—she was referring specifically to settler portrayals of Indigenous people, but it applies here:

If you can’t write about us with a love for who we are as a people, what we’ve survived, what we’ve accomplished despite all attempts to keep us from doing so; if you can’t look at us as we are and feel your pupils go wide, making all stereotypes feel like a sham, a poor copy, a disgrace—then why are you writing about us at all?

Miller doesn’t shy away or avert his gaze as he peels away a dozen layers of stigma. He uses the material that was given to him responsibly. The woman on the cover remains faceless, but by the last page we know she was loved.

—From CNQ 104, spring 2019

We post only a small fraction of our content online. To get access to the best in criticism, reviews, and fiction, subscribe!