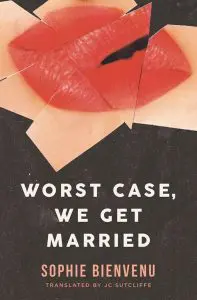

<br>Trans. JC Sutcliffe

<br>ReBook*hug, 296 pages

“Ill at ease”: that’s the phrase, antique but applicable.

With Sophie Bienvenu’s one-of-a-kind Worst Case, We Get Married I found reading sentences on pages discomfiting to the point of putting the reading experience on hold (aka, stuffing the book in my backpack) because of the reaction-fireworks key scenes managed to induce—feelings related to collusion, exploitation, resentment for being placed in the position of hapless voyeur, and, perhaps, fear of getting caught.

The principal reason for this emotional flowering? Exposure to explicit and erotic renderings of female teen and pre-teen sexual experiences with adult men.

Arguably, there’s nothing more forbidden for a male (even a gay one, like me) than to encounter the heterosexual couplings Bienvenu routinely describes. It’s telling that when gory, geysering bloodshed erupts at the close of the story, fatal, standard-issue violence is a relief compared to yet another detailed anecdote about a newly teenage girl freely giving a blowjob to some arbitrarily chosen guy in a stolen car.

The novel, which to appearances is set on a single day, is written as a kind of dramatic monologue. Across twenty-nine untitled sections, a girl, Aicha, speaks to a woman (addressed as “you”), who is recording Aicha’s words and taking notes. The person might be a legal counsel, police representative, or psychologist. Aicha is being interviewed because something has happened that she witnessed. In short, she’s a person of interest. Bienvenu teases out plot elements but doesn’t reveal the crime, its victim, or its perpetrator until the book’s closing pages.

In the interview room, Aicha’s emotional state is erratic, naturally, but the constants are her anger (at her “bitch” mother in particular) and her worldly persona (at thirteen, she has befriended the transvestite prostitutes in her downmarket neighbourhood in Montreal’s Centre-Sud: “You have to be a bit sick to sleep with a whore that’s a guy dressed up as a girl, right?” Aicha says. “They’re cool and everything, but let’s be honest, it’s not like guys want to get sucked off by them because of their wonderful personalities”). A habitual teller of half-truths who’s comfortable with the shock value of expletives, Aicha also talks knowingly about “super personal stuff” like methods for pain-free anal sex, the strategies of porno directors, and her identification with a chosen family of “queers, whores, junkies, and welfare bums.” As the interview progresses, Aicha reveals that she has volunteered to speak in order to help exonerate Baz, a guy in his twenties she’s developed a huge crush on. Her crush revelations extend to explicit sexual fantasies that Aicha summons while masturbating. Further, angry reaction to that unrequited crush situation results in Aicha’s first sexual experience—impulsive, in a car, at night, with a virtual stranger, and (porno)graphic in its bluntness: “He came inside me, it was running down my thighs, and it was hot and gross.” In turn, these recollections remind Aicha of when she was nine, in her view a lifetime ago. To the interviewer, she discloses how she used to watch Scarface with Hakim, her mother’s boyfriend, who was kicked out after Aicha’s mother discovered his sexual abuse of her daughter. Aicha’s recollection of those episodes involving the “pleasure and electricity” of Hakim’s probing fingers, however, is disclosed through frankly erotic language.

When you “like a guy,” Aicha informs the transcribing woman in the room, “it gets really tricky.” According to her, though, when “you give a blowjob to the brother of some guy from school” it’s a cinch. Yet, listening in on the one-sided conversation—inevitably picturing the scenes and assigning value to the sentences where pre-teen and early adolescent lust, yearning, sexual lyricism cannot be discounted—grows wildly distressing with its implications. To find actual eroticism in the words of a thirteen-year-old recalling her “fun” as a nine-year-old (via, of course, an adult author named Sophie Bienvenu, who turns forty next year)? To consider that a nine-year-old can pursue, agree to, and/or enjoy sexual experience with an adult male? To pathologize Aicha, as Baz does, as being “sick in the head,” or to entertain the idea that her sexual precocity is a direct result of her inherently perverse sexual experiences with Hakim?

Worst Case, We Get Married pushes these questions at the voyeur, Bienvenu’s unsuspecting reader. No doubt they’re provocative, if incendiary questions. They’re also proverbial—a can of worms—and seem nearly impossible to discuss in the public realm of 2019. And, not to mention: wholly impossible to answer.

—From CNQ 105 (Fall 2019)

We post only a small fraction of our content online. To get access to the best in criticism, reviews, and fiction, subscribe!