As we finally lurch into spring in Canada behind much of the rest of the world—the use of “lurching” meaning we can never really be sure it’s here until it’s here—I turn as I always do to my spring ritual of rereading one of my favourite books.

The Wind in the Willows is a natural for spring and I know it so well I don’t really read it, I dip in; a favourite chapter here and there, searching out Toad when I want to laugh at vanity and pomposity, but usually starting with Ratty and Mole interrupting spring cleaning for their picnic by the river. Nothing so properly immerses us in the universal feel of Wind in the Willows as that beginning, as generations have learned. But only on warm, sunny days does my personal ritual begin; when it gets overcast and suddenly cold again, I set it aside and wait.

The last few years have been different though, because I am using the marvellous recent edition annotated by Seth Lerer (Harvard University Press, 2009), a sumptuous treasure of a book. For people like me who thought they knew this book well, it’s not only wonderfully done—containing illustrations from many of the most famous illustrators who have tried their hand at it—it also contains incredible source material on Grahame and all his characters.

Toad, Mole, Ratty, Badger, and friends are given the sort of scholarly treatment one finds in Shakespeare and Alice in Wonderland studies (and even some less important modern writers, like Joyce and Eliot). And rightly so, for these beloved animals are now as established in literature as Mother Goose characters and The Wizard of Oz and all those classics that have imprinted themselves on the souls of so many young children. This is so common as to barely merit mention. My wife has seen The Wizard of Oz a hundred times and sings along with the movie. She clicks her heels, of course, but not in her red shoes, because they’re small models, not made for wear; they glitter down on her from the mantel.

We have friends, both professors, one of whom is slowly filling their house with artifacts relating to the Wicked Witch of the West. The husband and I may be discussing Montaigne and Pepys, but our wives discuss those images imprinted since childhood—plucky Dorothy and her friends and persecutors.

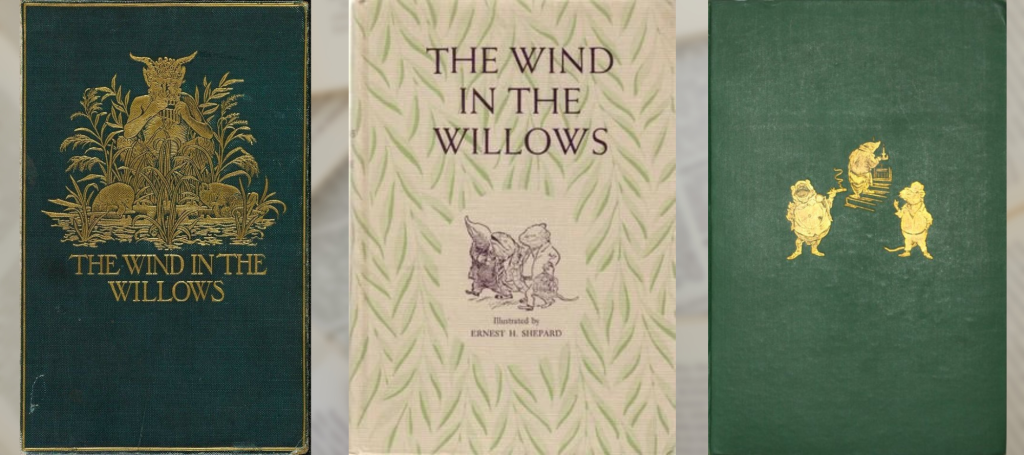

My friend Joe Brabant, the great Alice in Wonderland collector, filled a large apartment with Alice and her friends. He owned a ratty couch and two pieces of extremely valuable furniture—an eighteenth-century French desk and a seventeenth- or eighteenth-century Canadian bed—and nothing else. The closets after his retirement contained only a single suit and a ratty tweed jacket, that space also stuffed with Alice artifacts. While it is too early, and I am too old to do the same with Grahame’s characters, it will happen someday with someone. And, as with Alice, every ambitious new illustrator wants to try their hand. Aficionados have their favourites but still welcome new interpretations. Unlike Alice, whose first appearance in 1866 (the 1865 edition, being withdrawn because they didn’t like the printing of the plates, has become extremely rare and costly), was illustrated by Tenniel. The Wind in the Willows had no illustrations in the first edition of 1908, only a rather pedestrian (I think) frontispiece by Graham Robertson. The actual first illustration is on the covers of the first edition. The first cover has a gold embossed scene of Pan playing his flute in the reeds, with Ratty and Mole below him in their boat. On the elaborately gilt spine we find Toad arrogantly splendid in his driving outfit, complete with goggles, hands resting on his hips, a truly beautiful book cover, appropriate for such an instant classic. Neither Alice nor The Wizard had a cover equal to this one.

It was only later that we got illustrations, by Paul Bransom (1913), Nancy Barnhart (1922), followed by Ernest H Shepard, Arthur Rackham, and many, many others, right up to the recent brilliantly executed ones done by the Canadian illustrator Charles van Sandwyck. George Walker, one of Canada’s most prominent wood engravers, was the first Canadian to attempt Alice, but there will be many more. And The Wind in the Willows will go on forever, too, I’m sure, just like Alice.

But the information supplied by Lerer is the real treat in his scholarly edition. I think no repeat reader, certainly not I, will ever read The Wind in the Willows again without Lerer’s edition at hand. Or at least any adult. It’s not an edition for children; for them let’s just leave the mystery and wonder intact, there’ll be time for more understanding when they’re grown.

I have several books where every year or so I reread the book then watch the movie (or the reverse). Unfortunately, while I have a number of animated film versions of The Wind in the Willows, I don’t watch them as part of my ritualistic homage, for none appeal to me. It may be because they were wholly aimed at kids and are all animated. I don’t remember clearly, but I don’t think I’ve ever even watched one of them right through. I guess I’d have to wait, as with Alice, for us adults to be taken seriously. After all, we’re people, too.

But this year by chance I came on a reference to a Monty Python version of The Wind in the Willows which was said to be rare, since it had been a failure at the box office. Through Amazon I was able to track and obtain it very easily. It’s called Mr Toad’s Wild Ride and it met its promise, combining perhaps the greatest comedic geniuses of the twentieth century with a book and characters that seem made for them. It may be finally judged as some sort of weird failure in cinematic terms, but for aficionados of The Wind in the Willows it will continue to be a treat to savour. Like reruns of Monty Python.

And now I have a movie to rewatch as I reread the book every spring.

Over the years I have built a large but rather weird collection of The Wind in the Willows; weird for what is missing. I own the first edition of The Wind in the Willows, which I found with a damaged cover and had rebound in a design binding by Michael Wilcox, a Canadian whom I and Justin Schiller, and perhaps other aficionados, consider the best design binder in the world. I also own the second edition in a fine, original binding which bears precisely the same lovely gold-stamped cover as the first edition. But I lack several of the later limited signed editions illustrated by famous illustrators like Ernest A Shepard, Rackham, and Charles van Sandwyk. These are very pricey, and while I had sold many of them before I began collecting Grahame, the truth is I’m now really only interested in the secondary editions of The Wind in the Willows. I don’t want Grahame’s other writings. A few years ago our respected colleague David Holmes, who dealt in autographs, manuscripts, and books from that period and with whom I did a fair amount of business, died way too young. David had a truly important collection of Grahame, including several early inscribed copies of The Wind in the Willows, quite rare and valuable books. David’s daughter, Sarah, did me the great honour of offering the first and another early edition bearing nice presentation inscriptions. I wanted them very badly indeed, but my age and precarious health, followed soon after by this wretched pandemic, meant I was not able to contemplate the considerable expenditure they would have necessitated. Several years and several disasters later I still can’t buy them. I’m now at the stage where I’m afraid to inquire of Sarah if she still owns them for fear I might weaken and be tempted to mortgage the farm.

What I do pursue are all the modern illustrated trade editions, especially the many pop-up editions and segmented editions issued for young children, of which I now have quite a few.

I’m getting set to donate my collection, another reason I couldn’t buy the presentation copies. My loss, even with the partial tax credit, would be much more than I could sustain these days.

One of my great pleasures is giving books to children, from my friends’ and family’s children and grandchildren to the very young Halloween visitors we get every year (along with plenty of candy, of course—we don’t want our mission to spoil their fun).

At a certain age these kids move up the maturity ladder from picture books to beginning readers real books, and The Wind in the Willows is the first real book I give. They get a common child’s version, which I hope they like enough to later get the full version.

This year Theo, my cleaning lady’s son, will be six years old and I am fraught with anxiety that he won’t be ready or won’t like it. But I must chance it, it’s my mandate.

One last thing for whoever cares. My old friend Joe Brabant identified with and focused on, in his Alice collection, The Mad Hatter. While Joe was a distinguished, respectable, and conservative lawyer, I always thought that symbolic choice eminently appropriate. My focus in The Wind in the Willows has always been Mole, and my mind’s picture of his cozy den has always had the entire den shelved and full of books. Quite appropriately, I find myself living out the dregs of my life in two small rooms in our home surrounded with books, every single wall—even inside the closets—shelved and full, at peace and content, missing only my friends … and perhaps the spring picnic on the river. Just like my dear Moley.

—From CNQ 111 (Spring/Summer 2022).

We post only a small fraction of our content online. To get access to the best in criticism, reviews, and fiction, subscribe!