I don’t know what to do with Corb Lund. If Ian Tyson weren’t alive, then he might be the only great cowboy singer left in Canada; he’s certainly one of the best musicians writing about Alberta today. And he has the bonafides – his birth in Taber, his ranch upbringing in the southern part of the province to fourth-generation Albertans, even his stint playing in punk bands in Edmonton during his undergrad days. His ability to tap into a shifting, twisting narrative about progress and destruction in his explorations of the minutiae of blue-collar practices has also made him one of the great contemporary songwriters of labour and geography. The music he produces is accessible and often brilliant — a distinctly Albertan narrative to set against the Ontario themes dominating the airwaves.

Lund approaches Alberta via his family’s history, which he has a tendency to mythologize. And yet both the West’s history and mythologies are more complex and inclusive than he allows. Though Lund is clearly aware that Alberta’s economy and demographics have shifted, and that, even before that shift, the monolithic view of Western Canadian history was flawed, the latter nevertheless persists, overwhelming as the prairie sky, in his work. It might be churlish to demand Lund speak for those outside the ranching community, or for Indigenous communities, for urban Western Canadians— but the absences nag.

Part of this twisting narrative is how he plays off the history of the West. Lund’s best work is a kind of meta-effort at imagining Canadian culture through an Albertan lens; an understanding that, in Canada, Lethbridge seems closer to Billings than to Timmins. When Lund plays, he’s working through a number of factors, often in a self-consciously literary way. Most of how he plays, or what he discusses, functions in a kind of mytho-poetic mode. He knows the history of the West, knows that the play of authenticity must be made — for those outside of Toronto, Montreal, or Vancouver—with a deeply self-conscious irony.

I’m thinking about how he follows Ian Tyson. Tyson started as a rodeo cowboy, working in the 1950s at a ranch near Duncan, BC. His music career started when he could no longer ride. But Tyson didn’t become a musician in Victoria or in Duncan, or even in the Vancouver folk scene. He met Sylvia in the folk clubs of Toronto’s Yorkville, playing up the West to position himself against future superstars like Joni Mitchell, or Neil Young. The West’s regionalism became, in his hands, a kind of exoticism, one that he would continue to double-down on. His return to the West, and to rodeo life, became a logical consequence of his time playing the Albertan out East. Tyson bought his ranch late, got into cutting horses late. His work in the West wasn’t the kind of work that Lund was born into. Tyson’s music on albums like Cowboyography (1986) became a way of being more Albertan than Alberta itself; a kind of purposeful forgetting of his Eastern, coffeeshop roots.

Tyson playing the cowboy was both authentic (he ran a ranch, raised cutting horses) and inauthentic – he sang at a distance from the actual work; or, to put it another way, writing about the work he did became a way of separating his personae from his self. This is something that the West has always done well. The creation of the rodeo, for example, made games out of the ranch’s necessary labour. When Lund talks about playing in rodeo bands, he’s both part of the West’s culture, but also doubly separated from it. The rodeo band isn’t like the rodeo clown, who, when he isn’t riding, performs alongside the cowboys. Rodeo dances often occur after its events have taken place, so Lund’s performances function, in some ways, as a commentary on what’s just occurred just as the rodeo itself serves as a commentary on the work of the ranch. (In “The Horse I Rode In On,” he rides this “big sorrel gelding,” awkwardly, to the front of the stage. He’s in the centre of the action, but doesn’t quite fit in.) The performer who tells the story of the rodeo functions as a liminal figure, and the rodeo serves as a commentary on the work of the ranch. No rodeo can exist without a rodeo dance, but the rodeo dance is also a kind of parenthesis to the rodeo itself, which is a parenthesis to the actions required to put food on the table.

One can see this in how Lund talks about rodeo, often as a loss, or as a joke, or a ready symbol for the failure of spectacle to replace labour, or the ongoing decline of the West (be it economic, social, or familial). He’s been working on this theme for more than a decade. On his first album, Modern Pain (1995), he sings a rollicking, sing-along party song called “Good Copenhagen” about how Copenhagen spitting tobacco is a working-class, old-fashioned vice, and that cocaine – often, adulterated cocaine – isn’t nearly as good. (The title line is “Good Copenhagen beats bad cocaine.”) Lund is really making an ideological argument here; when he plays the song live, the Good Ol’ Boys sing along, seeing in themselves the virtues of old-fashioned, farmer and rancher-oriented, working-class Copenhagen, pitted against gauche, citified, executive-class cocaine. But in the first verse, even rodeo is considered a vice:

Well I partied with some crazy Calgary cowgirls

We ripped and snorted, kicked our heels and then

Two told me they got olde tyme religion

One says she’ll never barrel race again

The line is funny even as it marks loss. The giving up of barrel racing for God, of play for virtue, is only one way that a ranch or a rodeo can get lost. In “The Rodeo’s Over,” a song sung with Ian Tyson on the album Hair in My Eye Like A Highland Steer (2005), the party song becomes a lament. As with many cowboy ballads, the ride here is a metaphor for death. The last verse is yet another example of the rodeo as metaphor, part of Tyson’s work in the vein of “Cowboy Pride,” or Lund’s attempt to construct narratives in which a changing landscape signals interpersonal disaster, in the songs “Short Native Grasses” or “Gettin’ Down On the Mountain”:

So burn all the blankets and dry all the tears

We can always go further out west

And I’ll meet you out there in the vastness somewhere

I swear it but first I must rest

It’s a metaphor he’s relied on for more than a decade. In his album from last year, Things That Can’t be Undone, the rodeo becomes a metonym, not for either lost pleasures or lost landscapes, but for Lund’s own history. In the haunting “S Lazy H,” the rodeo that is over and the land that is lost is not the generic, but work that has been in his own family. Anyone who’s farmed in Alberta has a similar story about a family that got screwed over, or who screwed each other over. The story of land ownership and bitterness is a story found in Babylonian Epics and Hebrew Scripture. What makes Lund’s song less iconic are the explicit details, like the naming of the ranch itself.

It begins:

Well the roots of my people

They run deep on this place

I am sixth generation

On the S Lazy H

The verses between are a lament for what happened: a sister who moved East before “any cowboy could kiss her,” Lund’s lost opportunity, being stuck to the land when he could have done anything else, a fight about the splitting of the land with in-laws.

It concludes:

The last few years were a struggle

But I gave it my best

And I tried to go forward

On the land that was left

Well I have lived with the sorrow

And I will die with the shame

For now the bank owns what’s left of

The S Lazy H

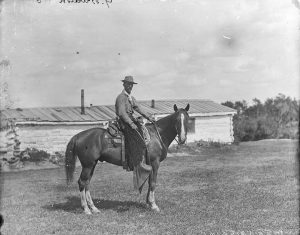

Courtesy Provincial Archives of Alberta.

How Lund abstracts biography by writing about his sister as a character is vital here. This isn’t a legal case, but a story that doesn’t necessarily have to be true — though in interviews promoting the album, Lund claims that the song is basically journalism, not journalism of the Tom Wolfe or Joan Didion school, but a plain, just-the-facts kind of record of what actually happened. I don’t know enough about Lund to confirm this, only that he begins by roping, and then loses his opportunity to rope, and that the loss of land is a loss of cattle, but also a loss of work.

When it comes to banks, Lund reminds us of Woody Guthrie’s lyric in “Pretty Boy Floyd”: “Some will rob you with a six-gun / And some with a fountain pen.” He is essentially correct, Calgary’s encroaching suburbs, the oil industry’s boom-and-bust cycle, the loss of small ranches, and the industrialization of agriculture having collectively caused an ongoing crisis for those family farms that fail to diversify. This has been a problem since World War II. But the sixth generation line is a shibboleth for long-term Albertans. In an interview with Maclean’s, Lund claimed that his family started the ranch in 1898, after most of the province’s major ranches were founded, and after the homesteading acts that would bring farmers into former ranch lands, and after the construction of the railroad.

The story of the S Lazy H may surprise those Easterners who view the West as still new, and Calgary as insignificant until the 1970s. For those with a long history in Alberta, the S Lazy H would be seen as both small and the mark of an arriviste. However, the number of people old enough to think that are vanishing.

*

In his essay, “Comedy and Humor In Country Music,” American academic and critic Don Cusic claims that country humour is “a private humour — a kinship humour — and much of it aimed at pulling the group together and fending off snickers from the outside.” Lund is often funny, and his jokes are almost always inside jokes, but it is also useful to think of how Lund uses the specifics of landscape outside of the jokes as metaphorical gatekeeping. His work is the construction of a prairie social identity. Being a fifth-generation Albertan is part of this, as is talk of genetically modified canola or alfalfa bloat, but also more general feelings of isolation, like the unique heartbreak a rancher experiences when his lover moves to Montreal to pursue a creative or academic career.

The loss of the ranch and the loss of rodeo are both ready symbols of Alberta, being direct, rather than oblique codes. This loss, sometimes humorous and sometimes serious, can be seen as extension of the West, and an indication of how Albertan stories fit into a larger tradition. The tradition of the ranch or cowboy song came to Southern Alberta from Montana via Northern Mexico. On his cowboy ballad, “Five Dollar Bill,” Lund tells the story of a bootlegger moving against the border in a way that both acknowledges and plays with this trope. On his album Horse Soldier! Horse Soldier! (2007), the horse soldier’s mobility becomes a metaphor arguing against borders.

Though “Rye Whiskey” isn’t a rodeo song, it’s a good example of how Lund uses traditional Western tropes, especially when you compare his performance of it to that of self-consciously old-timey folk singer Frank Fairfield. A traditional folk song, made popular by the American cowboy actor Tex Ritter, “Rye Whiskey” bridges the private world of agricultural workers and the public world of cowboy fans. Fairfield, with his distinctive moustache, his nostalgia, and his nervousness about spectacle, renders it an intimate folk song. Fairfield, meanwhile, is effectively cosplaying a nineteenth-century popular song/story. His songs are told with a banjo, the most popular instrument around the campfire (though instruments in the West were rarer in that period than is popularly imagined). Fairfield isn’t a cowboy singer though, and his performative intimacy has a nostalgia that argues against the history of folk music. It’s an aesthetic caught in amber, one bent on forgetting that works like Rye Whiskey had a century-long history, and one that explicitly forgets the influence of Tex Ritter and other Hollywood cowboys in its understanding of social and musical culture. Lund often uses “Rye Whiskey” as a concert closer. His version is usually raucous, and often segues into his own song, “It’s Time to Switch to Whiskey.” When he looks into the camera, Ritter allows for the separation between collective audience and individual viewer. By making “Rye Whiskey” his own, Lund forgets the politeness of old-timey music, but also refuses to self-identify as just a stage or screen cowboy.

This distinction, between what’s performative and what’s authentic, is a false one, but it’s a distinction useful to our understanding of how the construction of selfhood remains part of the ongoing problem of the West — what is “Western,” what is “Albertan,” and what is “Canadian” are all being variations on the endless problem of social identity. Lund can make an American song into one that’s distinctly Canadian by purifying it through his singular persona in the same way he makes Calgary — as opposed to Houston or Barretos or Cheyenne or Las Vegas — the centre of rodeo culture. Lund’s relationships connect to very small parcels of land, like the S Lazy H, forty acres, or quarter sections (a quarter mile, or 160 acres). The relationships and the writing cannot occur without that understanding of these parcelled bits of land. When Lund’s songs extend past the Alberta border, he often does so out of economic reality, it’s often to reflect a personal economic reality, like having to move to Saskatchewan because you can’t afford to live in Southern Alberta, or in Montreal with that aforementioned lover.

*

Lund’s relationship to Alberta is a psycho-geographic connection to the problems of the land, one possibly connected to the profound regionalism that moved to the forefront with the emergence of new country sounds throughout the 1970s. You can see it in Graham Parker’s California songs, Merle Haggard’s cribbing of the Bakersfield sound, Lyle Lovett ironically winking at Texans’ superiority, or Townes Van Zandt’s heartbreaking odes to Austin. It’s a geography that interlaces with the ongoing problem of work. Though there are contemporary alt-country singers who speak poignantly about the problems of labour, including the Drive By Truckers (“This Fucking Job”), or Kacey Musgraves (“Blowin’ Smoke”), Lund’s combining of Alberta’s geography with the explicit details of work seems slightly different, and marks his skills as a songwriter.

Part of this skill is an ability to separate the worker from the larger political context, or the marking of social loss in ways that are filled with both tiny and global apocalypses. (“Alberta says Hello,” with its chorus: Tell her I’m glad she’s doin’ well in Montreal / I talked to Laura, Jon, Kristine and Rich and Paul / It was tough for me to make it through the fall / Without you there beside me through it all, is made exceptionally plaintive by the implication that the loss is economic.) Lund speaks with unique skill about both class and capital because he’s smart about the loss of money. There are very few songs about oil workers, but a feature in Oil, Gas, and Mining found six, including Lund’s “Roughest Neck Around,” a song that celebrates both the danger and the thrills of “pulling dragons from the ground.” A few years later, Lund sang a survivalist anthem, “Down On the Mountain.” It’s an eschatological envisioning of what happens when the oil runs out; a song about people who are not prepared starve. That he can hold the worker in one hand and fear for him or her in the other seems to combine a prairie fear of both industry and government. Lund describes this loss with a precision that could mark a way of cutting a channel for other country musics to flow past Nashville’s monolithic river. In a Facebook discussion on the problem of Nashville and working-class representation, critic Carl Wilson said: “I kind of think that’s the current Nashville strategy, a way of triangulating between the white/pink-collar audience and the traditional blue-collar audience. Don’t mention anything that might cause some part of the listenership to dis-identify. It’s totally understandable but there is some loss of representation there.”

Lund provides his working-class and blue-collar subjects with a strategy of inclusion. He mentions much that might isolate a more general audience — one that might be unfamiliar with what a paint pony is, or the variations of canola, or the history of Mormon theological practice post-Brigham Young around Cardston, AB, but he does this in order to more deeply commit to specificity. In this he often sounds less like a songwriter than a short-story writer, or a literarily self-consciousness balladeer.

Constructing narratives around a social identity means risking a certain cultural narrowness. The absence of Indigenous voices in Western writing, in general, is scandalous. This is especially true of Western songwriters, outside of the possible exception of Johnny Cash. Given how much time Lund spends talking about himself as an Albertan, thinking about the province’s history, and trying to update the West’s legends, it’s surprising how little space he gives over to Indigenous peoples.

Think of Louise Erdrich and try to forget Louis L’amour. Even Annie Proulx’s second volume of Wisconsin stories, Bad Dirt, has a tale about First People in the West (especially “The Indian Wars Refought”). If Lund is positioning himself as a storyteller of the New West, one who knows his history, the rare mention of Blackfoot or Crow is deeply problematic.

Though he had an entire album of horse songs that includes a bravura track where he discusses the entire history of horse warfare in less than four minutes, the localized nature of his storytelling precludes other populations. Lund has spent time in cities like Edmonton, and has regular gigs in Nashville and Toronto — but he doesn’t write about cities, except those that have captured people he loves. He seems to believe that only white Albertans have been in the province for six generations. Like Gordon Lightfoot in his “Canadian Railroad Trilogy,” Lund fails to mention the role of the Chinese workers on the railroads, or the work they did in restaurants or laundries throughout the small-town prairies. In the song “Family Reunion” he talks about his “Blackfoot cousins.” But strangely for a writer so attuned to the West’s social nuances, he doesn’t have a song about the tensions between farmers, ranchers, and the Indigenous. It’s a pity because Corb could write the fuck out of a song about Treaty 8. As a writer whose ironic creations of a post-labour West partake in a traditionally epic style, he resembles nothing more than Larry McMurtry. But McMurtry’s genius extends to writing women and queer voices, work that Lund has so far avoided.

*

I started this essay with a discussion of not knowing what to do with Lund, and I continue in that space. I think that he’s one of the most talented Alberta songwriters of his generation. That he writes tales of isolation as skilled as the Icelandic/Manitoban fiction writer and poet, W. D. Valgardson. The very Westernness of his narratives have made him, like Tyson, a folk hero in Alberta and Saskatchewan, and mostly ignored in the East. That he plays in the big tent at the Calgary Stampede, and the much smaller Horseshoe Tavern in Toronto would seem proof of that, or that he’s on the prestigious but small Americana label New West in Nashville, after twenty years a critical darling but not a breakthrough star.

It occurred to me, as I was listening to Lund last year in my friend’s car, driving north of Prince Albert to the source of both the North and South Saskatchewan rivers, that he has become central to my understanding of myself as an Albertan. I’ve been away from Alberta for more than a decade, and he makes me homesick. His artifice, his ironic construction of self are as Albertan as his songs about hockey teams, stampedes, and natural disasters. But I’m not sure, even as a six-generation Albertan myself, if I’m the kind of Albertan Lund would recognize (because I gave up Alberta, or because I’m an urban queer, or because I’m scared of the West, whose mythology rests on a kind of push/pull embrace and refusal of a toxic nostalgia). My cousins —who are raising new babies on family land in the shadow of the foothills — are the people Lund seems to view as his own.

Or maybe Lund isn’t a problem to be solved, maybe he just is.

—A CNQ Web Exclusive (September 2016)